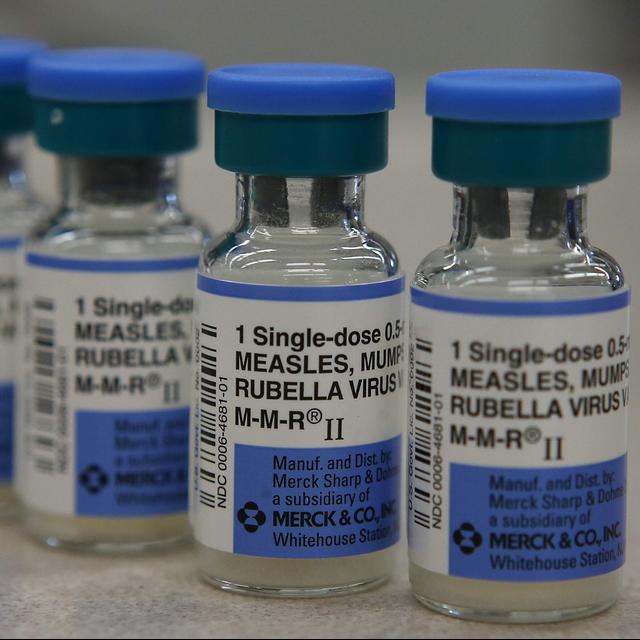

For kids, back to school means new school supplies, maybe some new clothes, and go into the doctor's office to get up to date on shots. Increasingly, parents are leaving that last one routine vaccinations off the to-do list. The CDC reported last year that the vaccination rate among kindergarteners is dropping, and more and more parents are seeking exemptions to school vaccine requirements.

And in August, Gallup reported that fewer Americans overall think childhood vaccines are important compared to 30 years ago. These trends help explain why Measles, a disease that the US eradicated with the vaccine 24 years ago, is back with the vengeance. We had a period of about three weeks in the United States back in the year 2000 where there were zero cases of Measles.

That's Dr. Paul Cslack, a medical director at the Oregon Health Authority, speaking with Oregon Public Broadcasting last week. Right now, Oregon is facing its worst Measles outbreak since the early 90s. It's also seeing a record number of vaccine exemptions for school aged kids across the state. People can get out of the requirement by choosing an exemption and going through the process. It was 8.8% of this past February. So that's the highest we've ever seen.

And that's probably enough for us to see sustained Measles transmission. Consider this. People are vaccinating their children at lower and lower rates. What does that mean for kids as they head back to school and for infectious and deadly diseases like Measles? From NPR, I'm Wannasomers. This message comes from NPR Sponsor, the Capital One Venture Card, earned unlimited 2x miles on every purchase. Plus, earned unlimited 5x miles on hotels and rental cars booked through Capital One travel.

What's in your wallet? Terms apply. See CapitalOne.com for details. This message comes from NPR Sponsor, SOTVA, maker of quality, handcrafted mattresses. Founder and CEO Ron Rutsen shares one of their core values. At SOTVA, we believe sleep does unlock a superpower. When you wake up and you're totally refreshed, you go after things more. And it all starts with being on the right mattress. And that's what SOTVA has been inspired by from the day that we started.

Visit SWATVA.com slash NPR to save up to $600 from now through Labor Day weekend. Truth, independence, fairness, transparency, respect, excellence. This is NPR. This is NPR. Fewer and fewer kids are getting vaccinated. At the same time, infectious diseases like measles are surging. Here to talk about why childhood vaccinations are on the decline. And what's at stake this school year is Dr. Steven Furr.

He's a family physician in Jackson, Alabama, and the president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. Welcome. Thank you, Glad to be with you. Dr. Furr, if I can, I want to start by talking about the measles outbreaks that we have been seeing this year. The state of Oregon, for example, is facing its largest outbreak since 1991. And if I understand correctly, this disease was eradicated in the United States back in 2000.

So help us understand why are measles cases surging in some states right now? Yeah, the thing you have to realize, a lot of these viral illnesses, they're all different, but measles is very infectious. And about 94 to 95 percent of people need to have had to have a measles infection or be vaccinated to have herd immunity. So therefore, you only have to have four or five percent people to not be immunized for an outbreak to occur.

So most of these outbreaks, about 86 percent of them have been patients who are unvaccinated who are the vaccination status is unknown. And the problem with measles, they can get severely ill, almost 60 percent of measles patients under five years of age get hospitalized. So generally, children get two measles vaccines. They get one when they're 12 months of age. And then they get another usually before they go back to school. So it's so important that they get both of those vaccinations in.

What do you think it is that's leading some of these parents to choose not to vaccinate their children? If I understand, most of these emerging cases of measles have been, and people under 19 is it that they've just perhaps forgotten how bad measles once was in this country? Yeah, I think that's a great point because, you know, people in this generation have been very fortunate. They've not seen a lot of these diseases, so they really don't know what they're like.

So when I was growing up, my grandmother had polio. I knew what it was like, and she had a deformed leg because of that. When they offered me a polio vaccine, I didn't hesitate to get it. And you know, when I was in residency, we had an infection called homophilous influenza, that often affected children.

It would give them ear infections, but they would sometimes get meningitis, and they would get an epiglottitis, which is a swelling of their airway, which means they would have to be hospitalized and sometimes even intubate it. Well, since that vaccine has come out, I haven't seen a case of that in almost 25 years. I think part of it, people don't realize how severe some of these infectious diseases can be.

And I think we take for granted, even the flu, people say the flu is a real commissment around a long time, but we forget how many people are hospitalized and die from the flu every year. Since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been poll after poll after poll that shows that Americans' confidence in vaccines is waning. You're on the front lines here. What do you think is behind these trends? I think it was a lot of disruption during COVID. The offices were often closed.

They couldn't get into their fanny physician or their primary care physician. So I think a lot of it, they lost the habit of going and doing that. Now I think part of that is in our healthcare system now. They might go to urgent care for some of their acute problems rather than going to their fanny physician's office or their pediatrician's office, so that those places that don't think about immunization.

So I think the biggest thing is to get fanny associated with their fanny physician, pediatrician, where they can talk about the immunization's granted. It can be very complex, both for kids and for adults. There's a lot of different immunizations that protect against various diseases. So it's really important for them to discuss with their fanny physicians what they need and what really will protect them.

Another thing that I wonder about is false information that's out there, misinformation about vaccines that parents and caregivers might be encountering that gives them pause. As a physician, how do you fight that or can you? I mean, I just talked with them and tried to reassure them. I talked to them about the consequences of not getting the vaccine, that the vaccines have of course been well studied with going through rigorous processes.

I think some people got a little bit nervous because they thought the COVID vaccines were rushed, but actually there was probably more signs in that that they actually, some form of that vaccine, had been around for a long time, the actual process. So it's just because we put all of our mind into doing that and focusing that we were able to get there. It's really a miracle that we were able to get those kind of vaccines that quickly.

So that technology that has been around is not something that's new. So I think one way you reassure them when the COVID vaccine came out, I told them, hey, I've taken it. My mother's taken it. My wife's taken it. My mother-in-law's taken it. So if I think it's safe for them and for me, I think it's safe for you.

You've mentioned a couple of reasons why people aren't getting vaccinated, the breakdown and well-care for children, but also a lack of exposure to the effects of serious viral illnesses. I'm struggling to reconcile this for myself because I mean, as a country, we have all just have the experience of living through a pandemic where people were dying in huge numbers before there was a widely available vaccine.

Do you have an explanation for how that didn't make a bigger difference in attitudes toward vaccination? Yeah, I think you've got to realize when you look at the history of vaccinations, just like when COVID vaccine came out and everybody was thinking the uptake was going to be 80-90 percent. I knew that wasn't realistic because we've been doing the flu vaccine for years and we never got over a 45 percent of people get vaccinated.

So there is a hesitancy about vaccine in many different communities. You could go back to the concern about the government and the fact that this might have been sponsored by the government and got started and you go back to the Tuskegee experiment. There's just some concerning communities. But the best way to get people immunized is to have their personal relationship with their family physician.

And I can tell you the way I get so many people immunized is the spouse will be in with a husband and he comes in and I'm saying, you want to get your flu shot and he says, yes, and then the spouse will say, you want to get to yours while you're here and they'll say, yes. So a lot of times, it's just a matter of the physician asking them and then when they ask and have concerns, then you can talk and address about those concerns.

But you know, it's really interesting because I'll see a family and the husband will have taken the COVID vaccine, the wife adamantly refuses. So if the husband's not going to convince her, the wife's not convinced the husband other way around, I'm probably not. But the most important thing is just to keep that relationship with the patient and over time, some of them will change their mind. But some of it I think is just denial.

Denial is a protective psychological defense we all have and you'll think everybody else will get this, but I'll never get it. We've been talking a good deal about vaccine hesitancy, but there's another factor that can contribute to lower vaccination rates that we should get into and that's access. Because over the past few years, we've been seeing physician shortages all over this country.

There have been pharmacy closures and I have to imagine that you're seeing this where you are to given that healthcare infrastructure is not always as robust in rural areas of this country. Do you think that right now it is harder for people to get vaccines in your view? I think it depends on when you talk about it, I mean, years ago none of the pharmacists gave vaccines so you had to go to the doctor's office. So there is more availability.

I think our public health structure probably is not as strong as it used to be where they have the ability to ramp up and vaccinate a lot. But I think the coverage for kids is actually very good either they've got insurance or even if they don't have insurance, every state has the vaccines for children's program that they can get where they're underinsured or uninsured together. They get that totally for free so our clinic does that.

So that's sponsored through the health department through our state Medicaid. So even if they don't have insurance they can get that for free. Now for adults sometimes it can be a problem they don't have insurance. So we would like to have something like the vaccines for adults just like we have for kids so that we would be able to get them covered also. Some of the trends that we've been talking about in terms of childhood vaccination rates may be concerning to some listeners.

So I want to ask you as a physician, what brings you hope when you think of about the role that you and your colleagues play in both keeping kids healthy but also helping to prevent the spread of disease? I think it gives us a good opportunity to really talk about vaccinations because people for many years kind of took them for granted and really didn't think about what they did and what they prevented and the ability to prevent diseases. I mean it's amazing.

We've got the ability with HPV vaccine to give this to teenagers so they'll never have cervical cancer. I mean that's an incredible opportunity there. So that ability to prevent disease is better than now than it's ever been. Dr. Steven Furr is a family physician in Jackson, Alabama and he's also the president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. Dr. Furr, thank you. Thank you. Great to talk with you. This episode was produced by Catherine Think. It was edited by Courtney Dorning.

Our executive producer is Sammy Yennegan. And one more thing before we go, you can now enjoy the consider this newsletter. We still help you break down a major story of the day, but you'll also get to know our producers and hosts and some moments of joy from the All Things Considered team. You can sign up at npr.org slash consider this newsletter. It's consider this from NPR. I'm Wana Summers. The candidates for November are set. I know Donald Trump's tight between now and election day.

We are not going back. A campaign season unfolding faster. Kamala Harris is not getting a promotion. Then any in recent history. Thank America. Great again. Follow it all with new episodes every weekday on the NPR politics podcast. Hey, it's Aisha Roscoe from NPR's up first podcast. I'm one of thousands of NPR network voices coming to you from over 200 local newsrooms across the country.

We bring all Americans closer together through free and independent journalism, music, politics, culture, and so much more. The NPR network, what you hear changes everything. And more at npr.org slash network.