In the early morning hours of August eighth, nineteen ninety eight, shots rang out in downtown Indianapolis. Casey Shane, a young man who had been known to frequent a gay bar in the area, was found dead in the driver's seat of his truck. A young woman who was delivering newspapers in the area witnessed the shooting. She described the gunman too police as a dark skinned black man wearing a black shirt and jogging pants with three white stripes down

the sides. Later, in a photo array and a live lineup, she picked out Leon Benson. Leon lived a few blocks from the shooting and was known to police as a drug dealer. When Leon was arrested a week later, he insisted he had nothing to do with the shooting. He'd been in a building across the street that night and dozens of people had seen him there. But at trial, the young woman who had identified Leon from the lineup did so again in front of a jury with convincing certainty.

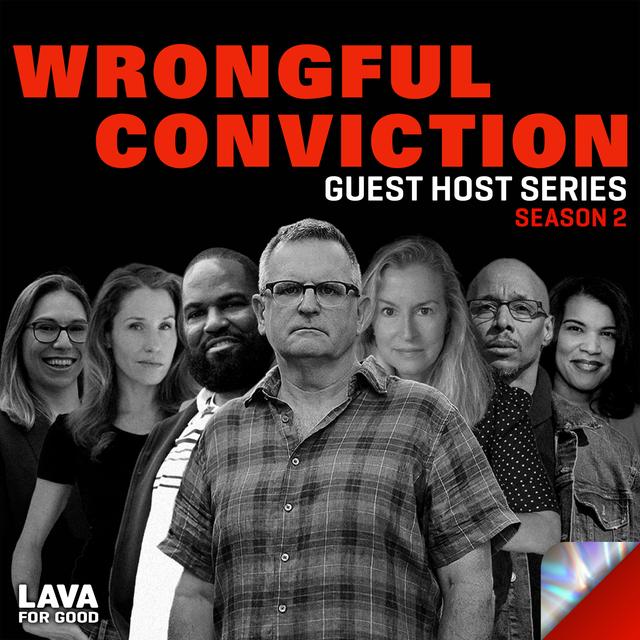

She had seen the shooter with her own eyes, she told the court, and she pointed at Leon Benson. But this is wrongful conviction. Welcome back to wrongful conviction. I'm kimbas Smith. Criminal justice advocate, formerly incarcerated individual, presidential clemency recipient, and author and executive producer. And I'm sitting in today for Jason Flahm, who is a good friend, longtime supporter, and I'm excited today to be here with Leon Benson. Hi. Leon, thanks for being on Wrongful Conviction.

Hey, thank you for having me.

And we also have us Laura Basilon from the University of San Francis Go School of Law, where she is the director of the Criminal, Juvenile Justice and Racial Justice Clinic Programs. Welcome, Laura.

Thank you so much for having us.

And thank you so much for your passion and the work that you do. Leon. So what was most interesting to me about your case was that during that particular time when you are arrested in nineteen ninety eight, there was this big, you know thing already with the war on drugs, but there was an influx now black and brown people going into the system. And so my case

was a drug case, a crack case. And so I know with my case, the prosecution withheld discovery information and just to read all the many errors that transpired with your trial, it just really struck a chur with me, and not to mention. I used to live in Indianapolis as well, so I'm really excited to just dive in. Can you tell us about your life before all of this happened. You know, where you're from, where you grew up, anything about your family life.

You know, first and foremost, I'm from Flint, Michigan, and I'm proud to say that. You know, Flint is a blue collar community, you know, the underdog. You know, we got that fighting spirit. I think I had a great childhood. I mean I didn't know I was poor anything like that. I was very creative growing up. I was able to see a diverse crowd of people and culture.

At a young age.

And you know, I participated in sports, played basketball, you know, things like that, you know, typical things of a kid. So I did have an affinity for hip hop, but I also started to have an affinity for you know, the fast life, fast money, things like that.

You know, growing up, I was a typical.

Kid who experienced gang violence, experienced street violence, things like that.

You know.

I eventually moved to Detroit when I was seventeen and and love Detroit. You know, I made my bones in Detroit very early. You know, fair feeling Puritan. You know, at this point, it seems like a very typical urban background. As I reflect back on my life, I see a lot of things that could have been a lot better, but they could have been a lot worse too, you know.

And at the time that this incident happened, what was going on in your life?

In August eighth, for nineteen ninety eight, I was twenty two years old, and at the time, what was happening for me in my life? It was like, you know, the the hip hop stuff that was going on with Tupac, you know, in Big Eie master P.

You know, this was the backdrop. You know. I was in Indianapolis, Indiana.

I had come down there, not to sell drugs or anything like that. I came down there as a professional painter, home renovator. I was able to renovate like eighty homes before I was laid off, and you know, unfortunately, you know, I got back into the street life. So the area I was in, it was a transit area in the near downtown area Indianapolis. It was a lot going on.

It was very transit, very moving, and this was one of the reasons that attracted me to this particular part of the city of Indianapolis because it reminded me of Detroit and Flynt.

And this was also the neighborhood where the crime took place. Laura, can you tell us something about the area kind of set the stage for what happened that night?

Indianapolis, the downtown part of it where this crime took place, was fairly violent. It was known for a place where you could buy and sell drugs, and as Leon also indicated, was this interesting mix where this is the late nineties, there was a lot of homophobia, and it was also a place where people who were gay could go to bars, including the Varsity Lounge and meet other people who were gay.

The victim in the case was twenty five year old Casey Shane. He was from Plainville, which was middle class subourbon community about twenty miles outside of Indianapolis. What was he doing downtown that night?

Our operating theory has always been that Casey Shane was there that night in that particular part of Indianapolis because he had visited the Varsity Lounge, and we know he had visited that bar in the past because witnesses had identified him as being there, and there's fairly strong evidence at this point to suggest that he was gay, but also closeted for the reasons that you might expect, which is that very very few people, even in extremely liberal places,

which Indianapolis was not, were out of the closet at that point in time. And so our theory is that he went out that night and went to the Varsity and had a few drinks and maybe had an interaction with someone there and then maybe arranged to meet them a couple of blocks away, which is where the actual crime itself occurred.

With all of that, can you run down roonologically the night of August eighth, nineteen ninety eight.

Yeah, so it was a fairly ordinary night in that Leon was hanging out at a place called the Priscilla Apartments, which was also known as Little Vietnam.

It was a building that I saw drugs out of, and at this particular point of the night, I'd been out there all day. So I came back to my headquarters was this building, and I was in the back of the buildings and by the steps, and I was there with Timothy Gaither with a whole bunch of other people, and you know, it was beer drinking, we smoking.

And then around a little after three o'clock in the morning, there was this sound of gunfire.

And we heard shots like by popow paw, and it was like they were so close.

And one of Leon's friends, Miss Shirley, who had just gone outside, saw what they believed to be this black pickup truck parked kind of idling outside across the street, and there was a man in the truck in the front seat who wasn't moving, and there was a man on the sidewalk who had fired multiple times into the vehicle, then walked away, walked back and fired again, And this was just a completely shocking, seemingly out of nowhere shooting,

and from Leon's perspective, all he heard were the shots.

You know, I stay in the back of the building for maybe twenty thirty minutes, so I left out that back part of the door and went to my apartment that was also in that direction, going like several blocks away.

And he kind of went about his evening and then only later realized that it was this young white man who was in the neighborhood and this was a really big deal that he had essentially been executed in his car, and the police just came in kind of swarmed into the neighborhood and essentially shut down business as usual there for a while because they were extremely intent on finding someone to arrest.

Now went on about my business, and it was a parade of police, you know, later on that day, and I didn't come back to the area for several days.

I think there was a lot of pressure in this case because the suspect who had been seen by witnesses was black, the victim was white. I think that cross racial nature put extra pressure on the police, and there was just a lot of heat in the neighborhood in the next couple of weeks, and a lot of, as I said, pressure on the police to solve this crime and really get someone in custody and charge them.

So Leon was nowhere around he heard the shot. What led to this investigation? How did they even connect Leon to the case?

Initially, the police were given leads that the person who committed the shooting was a man named Joseph Webster, and they had that information because there was talk in the streets that it was Joseph Webster, and there was other information, including from a man named Dakaria Fulton who had actually witnessed the shooting, that Joseph Webster had committed that crime, but it so happened that a young woman named Christy Schmidt was there at the scene. She was a white woman.

Her reason for being in the neighborhood was that she was delivering newspapers. So for your younger listeners back in the day, you would put a quarter in a box, you'd open the box and you would pull out a newspaper, and Christy was the person who would stack those newspapers, and that's what she was doing. She was in the middle of doing that when she heard the shots and she looked up and she saw the shooter and her initial description she said, he never got into the light.

And recall it's very dark to three o'clock in the morning.

She was one hundred and fifty feet away, a full block away, and according to the lead detective, a man named Alan Jones, when she was given different mugshots to look at, she was given Joseph Webster's mug shot, and she said that it was not Joseph Webster, and then detective Jones showed her a picture of Leon and Christy Schmid said that his face leapt off the page and that she was certain that this was the person that this was the shooter, and when that happened, the entire

trajectory of the case changed.

So you're saying this key witness pointed out Leon on a lineup, despite having only seen the shooter in the dark of night for a few seconds and from one hundred and fifty feet away.

And she said, initially to the detective on the scene, Detective Leslie van Buskirk, he had a dark complexion. And of course, as you can see all too clearly because we're all looking at each other and these little zoom pictures, Leon is very light complexed. There were a lot of things that didn't make any sense about her description, which also evolved and became increasingly specific and dramatic over time.

And I want to point out too that study after study has shown the unreliability of cross racial identification. They've been fun to be less accurate than just taking a wild guess. So, Laura, was there anything else about the photo identification or the lineup that seems sketchy.

Yes, there's a lot of opaqueness around that. They never recorded that interview. We have no idea what Detective Jones said to her. We don't know if suggestive language was used. We don't know how many pictures she actually looked at. She does not have a clear memory of that at

the time. And so once they had this woman as their witness, they built the entire case around that, which meant essentially that they developed tunnel vision, and it really became about propping up her account and making everything revolve around and reinforce what she was saying. And every time they received a piece of information that pointed away from Leon and toward Joseph Webster, they would bury it in the file and not turn it over.

And another thing, there was another witness who came forward as well, a neighborhood guy named Donald Brooks who had previously gotten into a beef with Leon, I think over a drug deal gone sour. He told detective Jones that the shooter was a guy named Detroit, which was Leon's nickname. Donald Brooks later went back on a statement, but we'll

hear more about that later. Leon. All of this came as a surprise to you because you were arrested on the fourteenth of August, about a week after the shooting happened. But originally you thought they were picking you up for something else.

Right that day, I was still in my drug business at the time. You know, my run in with authorities was I got caught with possession of cocaine and so I was on a misdemeanor of probation charge. So when the police rolled up on me and Shirley now sitting on the stool, they said I had a warrant for possession of cocaine and probation violation, and you know, I was arrested for that. We went to the police station and they tained me to the wall in the room.

And I just fell asleep. I fell out.

And then I was awakened. I don't know for how long. It was cold as hell in there, and they came, you know, Detective Jones and Van Buskirk, and it was interrogate me. They told me like, hey, what do you know about this murder? And instantly for me, I felt like this is a game. I was nowhere around, no murder scene. I got nothing to do with this stuff. I just held my own But I thought it was a joke that they had come to me about a murder and even saying that somebody'd seen me do it.

It was laughable. It was laughable.

My biggest mistake was not asking for a lawyer. You know, twenty twenty, hindsight is always there. But you know, when I start to understand the law, I realized that most people like me at the time, you know, twenty two year old, uneducated. Of course, you know, you had this notion that if you say get a lawyer, as if it's saying you guilty, you know, the system say you're innocent to proven guilty.

But it was quite the opposite.

For me.

It was guilty and to proven innocent. So I didn't know this at the time. So I'm volunteering my location where I was at, and I find out later that you know, the detective, you don't manipulated, you know this information.

You know he omitted.

Out of forty people in the building, you only can find two people who said they didn't see me. And I gave you at least ten twelve apartment numbers of people that see me right right, and even worse, even worse because I gave up that information. You know, I wasn't thinking that people, you know, even in the building, that they had seen me that day would probably be like, I don't want to get involved.

I'm no, I didn't see nothing what you're talking about.

And they was right to feel like that, you know at the time. You know, so as bad as it sounds, you know, a lot of us play this game with the system, and I'm talking to my people that's out there, you know, in the street life or whatnot. You know, on one hand, we want to, you know, be out there doing our thing in the dark, selling drugs, you know, moving the things that we do. But then on the other hand, we wanted to we still want to trust it.

We don't trust the police, but we want to trust the police at the same time, you know, come save.

Me, right, you know.

And I was in that type of frame of mind at that time, and honestly, as a citizen, whether whether I was an accused drug dealer, accused murderer, accused robber, or whatnot, the law in the system supposed to be impartial, and I was feeling like that, but that wasn't the case.

But you did eventually hire a lawyer to represent you, a man named Timothy Miller. How did he feel about your chances?

So he came to me and I gave him a little run down. He's like, yeah, yeah, man, I already know that. Man, We're going to get this case dismissed. You know, I just want twenty thousand. You might not have to pay the whole thing because we'd get this dismissed. Just give me a five thousand dollars retainer and you know we would go from there. Man, hey, I absolutely believe you, right.

And then your trial was set for May of nineteen ninety nine in Marion County Superior Court. So, Leon, what were you actually feeling as the trial date was approaching?

You know, I had a lot of different emotions. You know, I was very nervous. I had never been to trial before, so at this point, me feeling like it was laughable was over with.

I'm going to trial. I'm like, oh, man, oh they for real? You know.

So the state had a couple of our witness says Christy Smith, who pitched you out of the lineup as the shooter, and Donald Brooks, who had given your name to the police. But at trial, Donald try to recant a statement saying he didn't remember what he'd said to the detective Jones, and he didn't remember seeing you near the truck. And not only that, you knew that your

defense attorney had an acepisleeve. A man named Dakaria Fulton, Laura, can you tell us about Dakaria and why he was so crucial to the defense.

Basically, Leon, Joseph Webster, and Dakaria were all drug dealers in this area. They didn't work together, but they also weren't enemies. He didn't really have anything against anybody. He just told Detective Jones exactly what he saw. What had happened was he was in his apartment a couple blocks away. He decided he wanted to go smoke a blunt. He

needed some rolling papers. He starts walking towards the seven eleven and just by happenstance, he's literally across the street and he looks and he sees Casey Shane's park car, and he sees this man standing by the car, and he watches this interaction go down, and he's pretty close.

He's much much closer than Christy Schmidt ever was. And he recognizes the guy as Joseph Webster because he's wearing these very distinct Adidas jogging pants block with three white stripes down the side, but also because he and Joseph Webster had run into each other earlier that day, and Joseph Webster had been carrying a gun and showed it to Takaria, who told Webster, you're a fool. You need

to put that gun away. And so it was this very clear, strong identification from someone who knew everyone new Leon, knew Joseph Webster and really didn't have any skin in the game. And that statement did get turned over to Timothy Miller like a.

Week before the first trial.

You know, Timothy Miller had finally given me the January nineteen ninety nine discovery supplement, and in this it had Dakaria Fulton's statement, and I looked, I'm like, oh, man, this guy's saying he's seen it right. I'm like, man, look hey, I'm not finn to go home, right. So I go back to the sale block and I'm showing them. I'm like, look, man, I told man, look, they got the witness right there, like we giving each other hog fight. Like, bro, man, you going home. So I go to the first trial

that Karly wasn't there. Just the mere mention of him is what got a hung jury. In my opinion, I was able to listen from the hole and sell to the jury pool coming out and them saying, you know, where's that other guy on they mentioned him, but where is he at?

In the first trial, the jury hung sex to sex, so it was a split vert. There were six people who did not think there was enough evidence to convict.

I say this all the time that my trial wasn't a trial really of Leon Benson, but it was a trial of urban America against America, because everybody in my trial was people who were from the streets, people of color, and our challenge was these people in us. That's how I felt. It was a clear line drawn, and I got the raff of a that energy. I felt some nasty energy in there. It was nasty. But when they came back and said a mistrial, I wasn't necessarily relieved.

I was glad not to hear a guilty verdict, but I was figuring, like, oh, once we get to Cary Fault, I'm out of here.

So then there was a second trial about six weeks later, in July of nineteen ninety nine.

There were some major differences though, between the first and the second trial, and I think maybe the biggest one was that in the first trial, Timothy Miller called a guy named Tim Gather who alibied Leon because he had been sitting next to him inside the building when the shots were fired, and so that really did establish an alibi, and it's consistent with what Leon had always said. And in the second trial, and we don't know why he

didn't call him. I think one of the things that is completely frustrating and not explicable is that he never called Fulton, not in the first trial and not in the second trial. In the second trial, he also didn't call Timothy Gaither and so Leon didn't have an alibi, and once again he failed to meaningfully challenge Christy Schmidt's identification. And this time the jury came back with a guilty verdict. It was chaos in the courtroom. Leon was crying out

for God to help him. His family was crying. The judge had to admonish them. The other side of the courtroom was cheering.

You know, the Leon Benson was murdered in that courtroom that day.

That's what you witness.

You witness a murder, a legal lynchen And I understand the victim's family, they lost a loved one. He can never be returned. But I was I was deeply hurt by the tears. Guilty in a tear, you know, I start to feel and empathize with a deep level of what slavery months looked like, you know, back in the day.

Yeah, I say it.

It was burnt. It was kind of burnt me. You know. I went back to the hole and sell you know, you know, I cried.

I was like, damn, like this is real, Like I'm not gonna see my kids. I was outcast, I was killed, and I was buried with sixty one years of dirt to lie in the tomb called prison. And I was shattered, you know, so much so when I went to prison, I had what you call delusions of reprieve. Something good's gonna happen. God is gonna open up the door and for me. You know, while I was sitting in prison, I wore my coat and my boots in my bunk. They say, man, why are you doing that? Because they

gonna come get me. Man, you're tripping. I was broken, right, So that's the gist of it.

But I see it also as just not losing hope. You had to believe that you weren't gonna spend sixty some years in prison. So I'm really interested in hearing because I did six and a half years, and it breaks my heart to know that you spent twenty five years in prison, and so I just want to hear about your strength and how you spent your time in prison, especially two of ten years. At that time, I believe I read you were in solitary confinement. So how did you keep yourself strong?

So, you know, in order to see somebody at their highest heights, you must know where they being that they low was lows. When I explained to you why I was that I was shattered. I could have gave up, but you can never give up on yourself. And you know when I came in, you know, I fought from day one.

I hit the law library.

I learned how to really read a case law and understand it. And you know, I was eventually, you know, put on solitary for participating in the prison riot that I didn't even participate in. So I was left with the question why me? And that question was answered, why not me?

Why not me? You know? So I had to get myself together.

I had to eat, eat some spirit full, you know, eat some knowledge ful you know, every day. And one of the things that I learned when I was in solitary was acceptance, right acceptance. I had to accept that I was in that moment those circumstances, not the stance, the situation, but the things that are circumscribed around it. And once I started to accept that I got to go through this process, I became more creative with the tools around me. So my jail cell wasn't no longer

a jail cell. It wasn't solitary no more. It became solitude. It became a university, It became a healing center for me. It became, you know, a public speaking stage, you know, to the other solitary prisoners, the other eleven. So I did the best that I can do in there, and I impacted guys. My best moments in there was when I showed guys who were illiterate how to read, how to write right, when I gave somebody that was broken, man, I put them back together and gave them real confidence

and healing. See, they didn't see that when we was on the inside. When I had the mic, it don't matter. I'm the coldest ever, and I said it on record because I made them guys in their hope. That feel good, That feel good. That's what I do it for it right now?

Right well, Leon, congratulations on your self growth while and the shoe in solitary, and then also your motivation for you know, when you were in general population to try to help lift other young brothers that were in the system as well, and I'm sure you'll continue to do so while you're home. Laura, I want to circle back to you a little bit and talk about some things

that went wrong in Leon's trials, both of them. When you reviewed this case, did you see any evidence of ineffective counsel or prosecutor of misconduct, you know, that kind of thing.

There was. There was a misconduct by the prosecutor, not just by the police, and it was egregious in the second trial. And that is also consistent with my experience, which is that prosecutors tend to cross ethical and legal lines when the case is very close and they're worried that they're going to lose. And I think that's what was going on with this prosecutor, whose name is Randall Head, who later became a state legislator and is now prosecuting

people once again. But I think because the first trial was so close and he almost lost, he was absolutely determined that he was going to nail leeon this time, and so he did this absolutely unlawful thing, which is that when Donald Brooks, the second eyewitness, didn't say what he wanted him to say, which is that he saw LeAnn by the truck, and instead Donald Brooks started going backwards and being contradictory to his initial statement Detective Jones

rather than impeach him with the statement properly, he got frustrated and he said, I want to read his entire statement to Detective Jones into the record, all of it, and this is a very long statement. It covered the beef between Leon and Donald Brooks. It covered all kinds of things that made Leon seem like a really bad

guy and were completely irrelevant. And then to compound what he was doing, he said in closing argument that Donald Brooks had gone sideways and backtracked because quote, snitches get stitches, and that when Donald Brooks was in jail, he was afraid for his life. He was afraid he was going to be killed, and he implied not just that, but that Leon or his family was going to kill him,

none of which was actually true. And what that's called is basically evidence outside of the record, except it's not evidence. It's a totally made up story. And he just injected that into his closing argument. He made up a bunch of effects once again to make Leon look like a terrible, violent person, and Timothy Miller didn't object to any of that either.

And Laura, when you heard about Leon's case, what stood out to you?

There are really two reasons why my students and my staff attorney and I took this case. And the first one was that Leon has a very powerful advocate named Shannon Coleman, who's a woman in Philadelphia who's really made it her life's work to try to get people out of prison who've been wrongfully convicted, and she reached out

and asked me to take the case. But the second reason was that once I met Leon, it was just so clear to me not only that he was innocent, but just what a complete waste this was, because he's such an amazing human being and has so much to offer the world as an artist, as a thinker, as a brother, as a partner, as a father, as a member of the community. And the idea that Leon was just going to be rotting in there was so horrifying

to me. It just I couldn't live with that, And so I thought, you know what, this is a long shot, but we're going to dig deep, We're going to do everything we possibly can. And I felt like at the end of the day, if after a few years and we did everything we possibly could, I could live with that. But what I couldn't live with was listening to Shannon and meeting Leon and walking away.

Laura, you are a real one, and I'm sure Leon and I can both say that we're grateful for a turn. It's like you that'll take the long shots. Now we have to get to the events that led to Leon's conviction being vacated. Can you tell us about that process.

Leon's case was accepted for review by the Conviction Integrity Unit of the Marion County Prosecutor's Office, which was a new unit at the time, and I think maybe his case was the first that was accepted and the co director, Kelly Botter, was assigned to it. So we were really lucky that we had a true partner in the prosecution, the District Attorney Ryan Meers. He was very focused on making sure not that the numbers were really high in terms of convictions, but that the right people were being

convicted and that innocent people were not being convicted. And so Ryan Mehers had assigned Kelly and her counterpart to look back at cases where it seemed like maybe there had been a mistake or multiple mistakes that were made. And what was really tricky about Leon's case is that many of the issues that we had been talking about were what we call in the legal world litigated and lost, meaning that they had been raised at other times after

Land was convicted and rejected. And that included the misconduct that I described by the prosecutor. It included the failure to call Dakaria Fulton, It included the failure to introduce testimony about the perils of crossracial identification. All of those issues had been raised and lost, and so we had to find something new, and that was going to be very, very hard because almost a quarter of a century had gone.

And it occurred to us ultimately that maybe there was evidence that was provided by the original people involved in the case as witnesses that had never been turned over to Leon and his attorney, and so that ended up being the key that really unlocked the prison door, so to speak. In other words, we were all in agreement that once this buried evidence surfaced, it was really clear that the trial had been unfair and unconstitutional because there's a rule, the Brady rule, that says you have to

turn that evidence over and had been violated. And in addition to it being violated, it was very clear that had it been followed, the jury would have reached a different verdict.

You mentioned evidence that was buried, What exactly was that buried evidence and how did you dig it up?

So what we did was Kelly, our partner on the other side and the conviction Review Unit, she provided the actual police file, which no one in the history of the litigation had ever seen, including Leon, and so we went through everything in that file and then we compared it to the documents that have been turned over to Leon and Lo and behold pretty much every time Joseph Webster came up as a suspect, whether it was through multiple detailed crime stopper tips, or most crucially, a note

to Detective Jones from another detective citing three different people who had either witness the murder or who he had told he did. It was buried and Leon had never gotten those things. So we went to see Detective Jones. He had retired under difficult circumstances, he was older, ailing

and over a series of hours. Really towards the end of this interview, he admitted that he had not turned these documents over and that basically every time he wrote something down or received something that was handwritten, including this note saying my confidential informant saw Joseph Webster shoot the white boy and the head, that note too, had not been turned over. And so when we asked Detective Jones why, he said, well, that was my work product, and there

is really no such thing as police work product. They have to turn over everything in their file to the district attorney. And so once he said that, I remember, I just had a physical sensation in my body, like I just couldn't believe that he was saying what he was saying. That's when I realized that in that moment,

the case was probably over. And then we came back and visited him a few months later and he signed a declaration basically saying what he had said to us initially, and that was, in the end, the most powerful piece of evidence that really broke the case completely apart. And that was when I understood that that Leon was going to be going home.

And then on March eighth, twenty twenty three, Leon's conviction was vacated by Judge Chatries Flowers.

But I didn't know until March nine, about eleven in this and I was reading J. Prince The Art of Respect. I was reading that and they called my name, and you know, I left out and went there, and the council was like, hey, you got immediate release, you know, woo woo. So I did have a David Shappel moment, right, I did kind of feel like.

Man woo tang, you know, just slipping over my desk's right.

So I just pumped my fists and I went and got my property together and everything, and I was on my way down the walk like an hour later, you know what I mean. So I threw on my all white, you know, I threw my pair, my prayer shaw on.

I get there to the gate, and uh.

You know, the first thing when I opened up the door, it's like I was blinded by the light.

You know, I was being rebirthed.

And the first thing I did, you know, I iron at the most High in which I called the most High Yahweh. I said, hallelu yah barukata ya huah, which means blessed be the name Yahweh. That's what I did when I got out. I see my sister Valerie, and I heard my brother's voice, and I see my daughters, and I seen all my people who looked at like angels to me when they sat right there and they was looking and I could hear the chant truth never dies,

Truth never dies. And what you would see if you ever look at that footage, it's so authentic because I just was in a moment. That's what you're seeing. That's the core of me getting out of there. I laugh at it when I see it too. It bring me joy. That's how joyful I was, you know, with that to embrace the people who put in.

The time to believe me.

You believe me, so now you know I'm like a spiritual Muhammad Ali. I got the people, ain't on telling them what I can do with the people you believe.

Me leon, all of that, it's just phenomenal and definitely resonates within me. And I just think with your release and what you're doing now, I'm wondering how many of the boxes that you checked off with your goals of once you come out, because it seems like in five months, I'm sure you've checked off plenty. But tell us you know, what are you doing with your time nowadays? At you're home?

You know, I'm living here in Detroit, Michigan.

I've been doing a lot of things because I was practicing them, you know, on the inside.

I was mentoring. On the inside, I was.

Teaching, creating programs, performing organizing events, you know, things like that. One of my biggest highlights is, you know, I dropped the album Innocent Born Guilty. I recorded it on the inside.

I don't want to.

Tell you how when where you know, yeah, you know, I don't want to do that, but it was recorded inside. It's a soundtrack of what I was feeling in different times and whatnot. Beyond that, you know, I'm still active in community involvement awareness. You know, every chance I get, I put a word in for at risk youth. I connect with other organizations like organization Exanna Reads here in Detroit. They definitely been huge with helping me re enter the

back in society. I've been you know, working with the Streets Don't Love You Back, you know, these other nonprofits.

Anything that I can do to.

Bring awareness, you know, to Room for and conservations, to any type of you know, discriminations or injustices in the world.

Well, Leon, those are really wonderful organizations that are doing great work. We'll put links to them in our bio page so our listeners can show their support and also let them know where they can check out your album,

which I thought was pretty dope by the way. So again I feel so humbled and grateful to be able to have this opportunity to be a guest host to interview you both with wrong For convention podcasts, we always close with closing arguments and so just really wanted to know what the both of you all have to close with.

I guess I have two kind of calls to action. The first one is and in the time that it took between our filing the petition for Lean to be released in Leon's actual release, we did get increasingly uncertain about whether this was actually going to work and whether he was ever going to get out. And the truth of the matter is it's a major decision by a judge to overturn a conviction. We needed to respect that process.

I think Leon understood that better than we did. So one thing I will say to lawyers out there is listen to your clients. Sometimes oftentimes they know best. And the second thing I'll say is to the audience, because any one of you could be selected to serve on a jury, and it's maybe the most important thing that

you'll ever do, even though you don't realize it. What I would ask that you do when you're on that jury is really, really take your obligation seriously, whether it is presuming somebody innocent, or holding the prosecution to their burden, or understanding that your doubts are real. I think so often.

There was a juror on Leon's case who did have a lot of doubts in the second trial, and she felt sort of bullied and exhausted, and she got herself excused, she left the jury, and then they convicted shortly after with a replacement. And if she had just been able to hang on a little longer, maybe the result would have been different. She could have hung the jury again. So I urge people, when you're in the minority and

you're battling against the majority. Maybe it's even eleven people telling you you're wrong and you're crazy, and it's Friday afternoon and they want to go home, hang on, hang on to your conviction, because you are the person standing between this wrongfully accused person and a terrible injustice. And so I would ask people when you're being selected for a jury to be considerate, to be observant, and to be strong.

Well, I got two thoughts. I got one ounce of previncing is better than the town they cure. You know, do to things I mean as individuals as well as you know public servants do to things in the now that you can do to prevent having to go back right with a ton of cure. So if you just come with an ounce of prevention, let's just have harm reduction, you know, in our lives as well as in our public spaces. And the next thing is, you know, be

a part of the solution, not the problem. Don't let your silence be the action that you know perpetuates injustice in any form, let alone wrong for incarceration. It's so many things that we can do as a society, as individuals that can get the world out. Okay, maybe you didn't you don't want to get behind an innocence case. It might take too long for you. Maybe you don't want to get behind a particular movement. But what you

can do is small things. Sign a petition, leave a comment of encouragement to somebody you know, sometimes show up at a rally that's trying to you know, get humanity across whereas being blocked. And one thing I wanted to say too, this ain't my story.

This Casey Shane's story. He was killed because he was closeted.

Now because he's dead, he don't have no voice, and you know, his story should get out because the biggest injustice now is not me in prison anymore or the time that I'm lost, but as an individual you know, who was a family member to others, was killed maybe for a sexual preference. And you know, even though you know I'm a head of sexual guy, I say I'm an ally to the LGBTQ community because I'm being so considerate of what they go through and some of those

experiences I don't fully understand. But one thing I do understand is that we are all human. We perfectly imperfect. You know, Hey Helheim said we was perfect. We were made in their image. You know that's something that to even look at, you know, and Taul Ross, so everything that's here is supposed to be, you know, because it wouldn't be.

Thank you for listening to wrongful conviction. You can listen to this and all Lava for Good podcasts one week early by subscribing to Lava for Good Plus on Apple Podcasts. I'd like to thank executive producers Jason Blam, Jeff Kempler, and Kevin Bortis for inviting me to sit in today, and thanks to our production team Connor Hall, Annie Chelsea, Lyla Robinson and Kathleen Fink. The music in this production was supplied by three time Oscar nominated composer Jay Ralph.

Be sure to follow us across all social media platforms at Lava for Good and at Wrongful Conviction, and you can also follow me at Kenpasmith on Instagram or go to my website Kimbosmith dot com and purchase my book Poster a Child, The Kembusmith Story. Wrongful Conviction is a production of Loving for Good Podcasts in association with Signal Company Number one