In late August 1992, Randy Weaver and his family were refusing to come down from the remote Idaho mountaintop where they lived. Weaver, a fugitive on a federal firearms charge, has been holed up in a cabin near Naples for more than a year. The government thought Randy Weaver was a dangerous, possibly violent extremist. Randy and his wife Vicki thought the government was an agent of Satan on Earth. When it was all over, three people were dead.

and the government had spent millions of dollars to catch one man. We'll find out why the siege at Ruby Ridge unfolded the way it did, and think about some of the questions it raises. What should we do about white supremacists? Why has the story of Ruby Ridge become an enduring myth for the far right? And whose fault was it anyway? Subscribe to Standoff, What Happened at Ruby Ridge, in Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen.

I'm Leon Nafok, and I'm the host of Slow Burn, Watergate. Before I started working on this show, everything I knew about Watergate came from the movie All the President's Men. Do you remember how it ends?

Woodward and Bernstein are sitting with their typewriters, clacking away. And then there's this rapid montage of newspaper stories about campaign aides and White House officials getting convicted of crimes, about audio tapes coming out that prove Nixon's involvement in the cover-up. The last story we see is...

Nixon resigns. It takes a little over a minute in the movie. In real life, it took about two years. Five men were arrested early Saturday while trying to install eavesdropping equipment known as the Watergate incident. What was it like to experience those two years in real time? What were people thinking and feeling as the break in a Democratic Party headquarters went from a weird little caper to a constitutional crisis that brought down the president? The downfall of Richard Nixon was stranger.

Wilder and more exciting than you can imagine. Over the course of eight episodes, this show is going to capture what it was like to live through the greatest political scandal of the 20th century. With today's headlines once again full of corruption, collusion and dirty tricks. It's time for another look at the gate that started it all. Subscribe to Slow Burn now, wherever you get your podcasts.

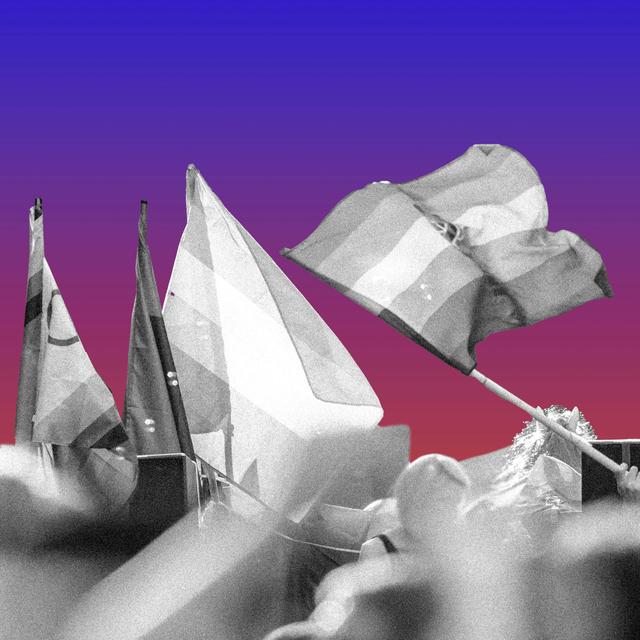

you're going to be my funniest guest ever. Oh my lord. No pressure. Yeah, no pressure at all. Tessa Skara is a comedian and a friend. I asked them to come into the studio because it's June and Tessa loves Pride. And also my birthday is in June, so. Oh, so it's the whole package. I'm kind of the mascot. I should have always known I was gay, but I didn't. Yeah. Yeah. No, I love June. Oh, it's glittery. It's rainbow.

There's community. And this year, it's so, so dark. Pride is feeling a little dark this year. For a lot of reasons. But a big one is money. For the last decade or so, many pride celebrations have been bankrolled by name-brand American businesses. Pepsi. UPS. Dyson. the vacuum cleaner company. This year, a whole lot of those businesses have pulled their funding back, prompting a lot of people to ask, what was corporate pride anyway? To be real.

Tessa always found the whole thing a little odd. One of my very favorite corporate pride items was, I think it was last year, Target had a shirt that said, live, laugh, lesbian. Which I just found so absurd. I love when corporate pride material like doesn't make sense. It was like it was generated by an AI. Right? Literally, literally. It's like a Mad Libs of like queer advertising. For the last few years.

Every June, Tessa would actually host a comedy showcase that they called Corporate Pride. It started back in 2021. That year was the year that we really, really started to notice just like ads that felt almost satirical. Tell me about one. Well, one that really comes to mind is the Postmates bottom menu. What? Can you explain this, please?

This actually feels like a lie. That's what I mean. When I saw that, I was like, this can't be real. And it is real. Literally, here's the food you should eat if you want to bottom, which is a sexual position. And there was a whole like stop motion ad where they had like eggplants in leather and like a peach wearing a jock strap. And I was just like, you know, Postmates, we actually don't need this.

They invested in it, though. Yeah, they invested a lot in it, and I really feel strongly that it helped no one. The Corporate Pride show was all about poking fun at this absurdity. Tessa and their comedy partner imagined silly futures and products for Pride. Like, would anyone buy a rainbow gun? It's a pride march. March it out, baby. Now sit down. This isn't about you. It's about me. Every year, there was more to lampoon.

When I heard you weren't doing the Corporate Pride show, I was like, is it because the joke's over? I mean... Not really. I wish I could say that was the reason why, but I think there still is so much to make fun of, you know? Yeah, what would you do if you were doing Corporate Pride this year? Yeah, if we were doing Corporate Pride this year, I would want to do like an apology tour.

for all of these corporations, you know, like ExxonMobil. I'm so sorry that I that we changed our logo to a rainbow and all the damage that that caused, you know, because that's what I feel like is happening. I feel like they're saying, oh, we caused so much harm and we're not going to. cause that harm anymore and it's like actually you did nothing

A lot of these companies, they pinpointed us as an advertising block and thought, wow, what an unmined resource. And they also, you know, I always felt like the corporate pride advertisements were more for straight people than for gay people. Like, gay people are laughing at the bottom menu, but I'm sure there was some well-meaning straight person that was like, you know what, let's use Postmates instead of Seamless tonight, because I saw a really eye-opening ad on the subway.

Today on the show, corporate pride may be dead, but is pride itself rising from the ashes? I'm Mary Harris. You're listening to What Next. Stick around. Hey, it's Anna Sale, host of Death, Sex, and Money. I talk to a lot of people on my show about sensitive parts of their intimate lives. And one thing I hope I would never do is share someone's personal story if they didn't want me to. That's the topic of a new episode in our feed with writer A.J. Delario.

who in 2008 was the editor of the sports site Deadspin. And one of the stories he wrote was about how Brett Favre, the world-famous NFL quarterback, sent a Jet sideline reporter named Jen Sturger messages and allegedly a lewd photo to proposition her. Jen told AJ about that, but she asked him not to do a story. I remember getting off that call and being like, Jen, I think you just overshared. And I was like, no, it's fine.

AJ did the story, it went viral, and is still what Jen is most known for online. In this episode, Jen and AJ talk together about that betrayal, the years of silence that followed, and the unexpected way they reconnected. And we both do some Googling, basically just like, is this the person that I had burned years ago? And it turned out that it was. And I said, well, I guess this dog will die. You can listen to this episode and all episodes of Death, Sex and Money wherever you get podcasts.

Hey there, Slate listeners. It's David Plotz, one of the hosts of the Political Gab Fest, a podcast where informal and irreverent discussion meet sharp political analysis every week. On our recent episode, Only 100 Days, we had a fascinating conversation with Washington Post reporter Dan Diamond about the long-term impacts of the doge cuts on U.S. healthcare and health policy.

What Doge has done in terms of cutting programs and people, that has immediate consequences and also long-term risk that's getting baked into the system that I don't think anyone saw coming. One of those risks is to food safety. They say that they're protecting the food inspectors, but they have cut around those inspectors. Inevitably, there are going to be fewer food safety inspections because there's a smaller apparatus to do it.

Join me, along with CBS News' John Dickerson and Emily Bazlon from The New York Times, every week to stay on top of the news without getting bogged down. Listen to The Political Gab Fest, where you can come for the debate and stay for the cocktail chatter. That's Political Gab Fest. wherever you get your podcasts. After chatting with Tessa, I called up my Slate colleague, Christina Cotarucci.

She's been doing all sorts of reporting on corporate America's evolving relationship with pride. Pride's pretty personal for her. Christina, do you remember what your first pride was like?

Yes, I was 23. It was 2011. And I had just graduated college the year before. And in my senior year of college had kind of... come out and realized, you know, this whole dating women and dating trans people thing is not just something I was like trying out for fun, but actually who I am and the thing that I want to do for the rest of my life. So I went to Pride with my partner at the time, and it was totally overwhelming. How so? Tell me more about that.

I had never seen so many different kinds of queer people in one place. Just seeing... hundreds, maybe thousands of people of all ages and coming from all over the area to all parts of the city, all parts of the region, wearing kind of their best, most them. clothing kind of expanded my sense of what my new community was. And I also felt very much like, you know, as... femme-presenting person, this was a place where I was like, oh, I'm also recognized as queer here.

No one was making any assumptions about you. Right, exactly. I was like, I actually feel like I'm recognized here and I belong here and almost feeling like I'm so happy about this club I just joined. Were there a bunch of corporations there? Like, were there sponsors for Pride in D.C. back in the early, like, 2010s? There definitely were. I mean, D.C. has had corporations sponsoring Pride for decades.

But it didn't bother me at all because I kind of felt like, you know, this was just a huge party. I'm kind of not paying attention to the corporations really. And to the extent that I noticed them, it feels a little bit just. festive and fun and, you know, an extension of the rest of my life in a capitalist society where there's just advertisements everywhere. And in this case, they're rainbow. Was there a point where that changed?

Were the corporations, it felt like they sort of took over? It was a few years later when I, you know, maybe it was my fourth year going to the Pride Parade. It felt like half the parade was just companies and their floats. I started to feel a little strange that I was I'd be cheering for, you know, a community group of queer and trans young people. And then I'd be clapping for. Facebook, you know, like it just, it felt like, why am I honoring these businesses?

on a day that's supposed to be honoring us. Yeah. And it started to make me feel a little bit sick to my stomach. Like it's supposed to be kind of a fair trade, right? Like they're getting... Visibility in front of a community that has, you know, robust spending power. And we're getting a nice big party that they're bankrolling and we get to feel warm and fuzzy that companies love us. But I started to realize that.

You know, we weren't getting as much as they were out of the bargain. I mean, you recently wrote this piece for Slate. about pride, and he talked about how there's always been a push and pull over corporations being a part of the celebration, even as far back as the 1970s. Can you explain?

Yeah, so in the 1970s in San Francisco, back then it was called Gay Freedom Day, this celebration every year that was commemorating the 1969 Stonewall Uprising. And there was a group of kind of... radical activists in San Francisco who felt like the Gay Freedom Day celebrations had gotten...

too beholden to businesses and not political enough. And again, this is less than a decade after Stonewall, which kind of kicked off these annual celebrations that we now call Pride. And these weren't national corporations, but they were... local businesses, gay bars and the like, that these activists felt...

that what should have been, you know, a protest and a show of visibility and something that felt more political and tightly connected to the big political issues facing queer people at the time had turned into what they called a glorified bar crawl. This sounds familiar. I know. And it really is kind of like there's nothing new under the sun here because our community has been having this internal debate. Yes.

the very beginning of Pride, about how much should these annual commemorations of an uprising against police harassment be a party, be money-making opportunities. versus, you know, more of an organic moment for resistance. You started to really embrace your... feelings about pride, your kind of divided feelings about pride. You tell this story about how in 2017, you went to a pride march and you actually protested. Can you explain what went down and why?

Why your approach sort of seemed to change then and what it was that made you change. You know, 2016 was sort of the last time I went to the Pride Parade. Donald Trump was running for president at that time and everything felt more politically charged. And watching some of... These floats roll down the parade, specifically arms manufacturers in D.C. You know, in our parade, we have Lockheed Martin. We often have Northrop Grumman. That is so D.C. Yeah. Tell me about it.

It felt, you know, not just kind of dissonant with the purpose of Pride, but pretty disgusting that... our community would be honoring these companies for not being homophobic, I guess, or for having gay employees. When they're manufacturing weapons of war, you know, what does our community really stand for if that's the kind of thing we're honoring in the parade? So the next year, a group of activists organized a series of blockades. We were protesting.

Lockheed Martin, Wells Fargo, who was a lender to the Dakota Access Pipeline that, you know, the Standing Rock protests were about, and the Metropolitan Police Department for their history of violence against Black. people in D.C. But you said at one point someone got in your face and yelled because you were blocking a float, a Lockheed Martin float from passing. Someone got in your face and was like, you're ruining pride.

Yeah, I thought that people would be a lot nicer to us. I think I underestimated how committed people felt to this big corporatized parade. And so sure enough, when we blocked the Lockheed Martin float, which caused a delay in the parade and they had to reroute it, there were people throwing things at us, screaming at us. You know, certainly some people coming out to give our support. But this guy, like you said.

you know, came up right in my face and screams that I was ruining pride. And that idea was so foreign to me that... Me stopping this Lockheed Martin float that literally had a model of a warplane and a drone on it. Was somehow ruining pride. I was like, what is pride for you if this is ruining it? And it kind of made me realize that we had such different ideas of what pride should be. And, you know, that's still an open question today.

What's interesting to me is that I think the crescendo of corporate pride happened throughout and during Trump's first presidency. And I'm saying that because I feel like now when people are talking about corporate pride is over and corporations are pulling out of pride, people are seeing it as a result of Trump and Trumpism, right? But actually, like, peak corporate pride was during Trump.

Right? Oh, yeah. And that's the big difference between the first Trump administration and the second one. In the first one, a lot of people in corporate America were... kind of openly saying this is not normal we don't support trump and not falling in line behind him This time around, you know, he won the popular vote. He has got a lot more of a coherent agenda that he is very capable of carrying out.

businesses have sort of put their finger to the wind and said, you know, it's actually in our interest to get behind this guy. And so we've seen it in a lot of big companies where they're kind of doing whatever Trump wants and trying to curry favor with him and the rest. of the MAGA movement. When do you think it turned? So during the Biden administration, even before Trump was elected the second time, you saw...

a growing right-wing movement against LGBTQ people. Republicans had been kind of quiet on LGBTQ stuff for a while. It felt kind of like a settled issue. Gay marriage was legal across the country. That happened in 2015. All of a sudden, these right-wing legislators started targeting trans people and realized that if they couldn't push back against gay marriage anymore, they're going to start targeting a smaller and more vulnerable demographic.

And that's when corporations actually started pulling back from corporate pride was when there were these kind of small but very loud right wing activist campaigns against things like. Target's pride collection and, you know, Starbucks having pride decorations and Budweiser having a pride marketing campaign. Yeah, I really pinpoint it with the Bud Light. campaign with Dylan Mulvaney, a trans influencer.

This month, I celebrated my day 365 of womanhood, and Bud Light sent me possibly the best gift ever, a can with my face on it. Check out my Instagram story to see how you can enjoy March Madness with Bud Light and maybe win some money too. Love ya! All of a sudden, all of these right-wing people just came out and trashed Budweiser. And it really, to me, that was the beginning. Like things, all of a sudden, the corporate support for...

LGBTQ people began to crumble. Right. And, you know, for me, I was kind of surprised to feel disappointed by that because for years I had been... disappointed by the corporate involvement in Pride and wishing that they would back off and wishing that we weren't giving them so much credit for doing literally the very least.

But all of a sudden, when it started to go away, I realized that I had kind of bought into what it meant, which is not necessarily that corporations were doing anything for us, but that... they reflected something about America, which is that LGBTQ rights had become so mainstream and kind of banal that... Even Raytheon was bought in, you know, and Bud Light. And now all of a sudden they weren't. And so I saw it more as a reflection of where America was going. And it was disturbing to me.

After the break, Christina offers a roadmap from Red America on what Pride could be, even without all the big bucks from corporations. In late August 1992, Randy Weaver and his family were refusing to come down from the remote Idaho mountaintop where they lived. Weaver, a fugitive on a federal firearms charge, has been holed up in a cabin near Naples for more than a year.

The government thought Randy Weaver was a dangerous, possibly violent extremist. Randy and his wife Vicki thought the government was an agent of Satan on Earth. When it was all over, three people were dead. and the government had spent millions of dollars to catch one man. We'll find out why the siege at Ruby Ridge unfolded the way it did, and think about some of the questions it raises. What should we do about white supremacists?

Why has the story of Ruby Ridge become an enduring myth for the far right? And whose fault was it anyway? Subscribe to Standoff, What Happened at Ruby Ridge, in Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen. Hi, I'm Josh Levine. My podcast, The Queen, tells the story of Linda Taylor. She was a con artist, a kidnapper, and maybe even a murderer. She was also given the title The Welfare Queen

And her story was used by Ronald Reagan to justify slashing aid to the poor. Now, it's time to hear her real story. Over the course of four episodes, you'll find out what was done to Linda Taylor, what she did to others, and what was done in her name. The great lesson of this, for me, is that people will come to their own conclusions based on what their prejudices are. Subscribe to The Queen on Apple Podcasts or wherever you're listening right now.

OK, so we talked a bit about all the ways corporations have gone all in on pride and now seem to be like tiptoeing away, which has had real consequences. Like you look at the. budget for New York City Pride, and they have a shortfall of $750,000, which is huge, simply because corporate sponsors are pulling out. But you did all this work looking at how...

Pride is going to be celebrated not in the big cities, but in small-town America. And you actually found it to be kind of hopeful. So I'm hoping you can tell me a little bit about when you dug in and looked beyond corporate pride, what you found. I loved reporting this story because I went into it intending to report a story about how prides were being.

harmed and hampered by the Trump agenda and this rising conservative wave against LGBTQ people. And instead, what I found were small prides in, you know, tiny towns and small cities across the country in conservative areas that were certainly taking greater security measures than they had in years past. But we're springing up in new areas like just in the past year or two.

and thriving beyond all expectation. Almost to a person, these organizers were telling me that, you know, I started my pride and... 2023 and we expected 50 to 100 people and a thousand people showed up and, you know, it was 2000 the next year or something like that. I mean. There was there's been such a built up demand in these small places where it really just takes a couple people and a vision to make a pride happen without any corporate involvement.

Tell me about one town. Like I know you talked to someone in Waverly, Iowa, which is a town of 11,000 people. How did they end up with a pride celebration? There's this person, Andy Hansen, who I spoke to, who's on Waverly, Iowa's Human Rights Commission. And... Andy and their colleagues have been wanting to have a pride for years. But, you know, it's always sort of on the bottom of everyone's to-do list because it's never happened before. And they also didn't want to have it just be like...

every other pride. They wanted something that really felt like Waverly. And so last year, this, you know, queer person in the community came to the commission and said, what if we just floated our kayaks and canoes down the river in the middle of town. Instead of a parade, we'll have a boat float. And they loved this idea. And this year...

They're going to have their first pride ever in this town of 11,000 people. And they've experienced, you know, quite a bit of community pushback, but also a lot of community support. What was the pushback about? So there was a... A group of 15 pastors from the area, you know, from different congregations who sent a letter to the Waverly City Council that said this is promoting immorality. They actually kind of cited...

reports from right-wing news outlets that said, look, pride celebrations can get pornographic and indecent, and this isn't going to be safe for kids. It's hard to do too much when you're canoeing. To be real. That was the argument. And, you know, also people will have problems with drag performances, but the city council held firm. And so they thought they were fine.

But then this bill came through the Iowa legislature, which said you can't spend any city funds on DEI programs. Now, this was going to be a city-funded boat float, you know, Waverly Human Rights Commission funded. And so they thought they were going to have to find other sponsors. So, you know, local businesses kind of stepped up and said, if you need us to fund it, we will.

But then it turned out that that law won't go into effect until July. So they're good for this year. But the whole experience and seeing how much support has sprung up in response to the opposition. Now, Andy and the other organizers are like, you know what, we need to do this every year. There's so many people who want this to happen. And especially now, especially with these.

anti-queer, anti-trans laws coming through the state legislature, this is a good time to start a new pride, which I think can seem counterintuitive to people. You know, like I, you know, naively went into this story thinking that the anti-queer and anti-trans wave would be pushing people back into the shadows a little bit. And that's the opposite is happening. Well, it's like an interesting stress test.

For the idea of pride. It like makes you ask this question of like what pride's actually about, you know? Yeah. And I asked these people who I interviewed, you know. what do you want out of this? And for people who had already had their first Pride last year or the year before, what did you get out of it? And a lot of them said, we need Pride more than ever now because...

People need to experience the good parts of being trans and queer, the parts that are about community and art and a shared history and a shared future and support and creativity and whimsy. incredible dance parties. And to be together, I mean, thinking about the experience of my first pride, there's a saying, every pride is someone's first pride. I get a little choked up every time I say that because...

Every year, there are more people coming out who haven't experienced that before, who haven't been around hundreds or thousands of other people like them, who've come before them and who are there to support them. And especially in some of these towns where there were people. coming to these first prides and told the organizers, I actually didn't know there were this many queer people in this town. And now I do. And it completely changes people's perspective of what their future can be.

Did you come away thinking that these smaller locales had something to teach the big cities that are kind of feeling screwed because their corporate money is disappearing? Absolutely. I think prides in big cities have become so big and our expectations have gotten so high for these massive concerts and festivals and parties.

that we've lost sight a little bit about other possibilities that could be more meaningful. And it can feel a little bit sanitized too when it's too corporate. And hearing about these really... homespun, smaller, but still, you know, thousands of people celebrations. My favorite was the one you found on a farm. Oh my gosh. Yes. Pride can be on a farm. And there were parts of...

big urban prides now that just seem completely incongruent to me. Like, why are we hiring these A-list straight musical performers to do a concert at Pride? It's like if you want to go to a concert, go to a concert. If you want to go to Pride, like have some local queer performers on that stage. And what people are getting out of it. feels very different from what you can get out of a big corporate pride celebration, which is an actual connection to the people who live where you do.

You know, you don't get that when you're just standing on the sidelines of a parade cheering for a big company. You get that when you're... surrounded by your neighbors and, you know, watching the drag queens that never got to perform in their hometown before and are up on the stage. You know, obviously there's... Small town prides and big city prides are always going to feel different. But I found a lot of hope in thinking about the modes of creativity we can employ with.

fewer funds in big cities that might make our prides feel even more meaningful and special. Christina, I'm so grateful you came on the show. Thanks for doing it. Thanks for having me. Christina Cattarucci is a Slate senior writer. She's also the host of Outward, Slate's podcast about LGBTQ plus life and Slow Burn, Gays Against Briggs. Earlier in this episode, You heard from Tessa Skara. They are a comedian, musician, and the co-host of a comedy show called Corporate Pride. And that's our show.

What Next is produced by Paige Osborne, Elena Schwartz, Isabel Angel, Rob Gunther, Anna Phillips, Ethan Oberman, and Madeline Ducharme. Ben Richmond is the Senior Director of Podcast Operations here at Slate. And I'm Mary Harris. Go track me down on Blue Sky. Say hey. I'm at Mary Harris. Thanks for listening. Catch you back here next time.

In late August 1992, Randy Weaver and his family were refusing to come down from the remote Idaho mountaintop where they lived. Weaver, a fugitive on a federal firearms charge, has been holed up in a cabin near Naples for more than a year. The government thought Randy Weaver was a dangerous, possibly violent extremist. Randy and his wife Vicki thought the government was an agent of Satan on Earth. When it was all over, three people were dead.

and the government had spent millions of dollars to catch one man. We'll find out why the siege at Ruby Ridge unfolded the way it did, and think about some of the questions it raises. What should we do about white supremacists? Why has the story of Ruby Ridge become an enduring myth for the far right? And whose fault was it anyway? Subscribe to Standoff, What Happened at Ruby Ridge, in Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen.