[SPEAKER_07]: our press secretary gave all turn to the facts to that. [SPEAKER_02]: My goal in this definition was to be crucial, but not particularly helpful. [SPEAKER_03]: Welcome to Unspon, the podcast that makes you better at finding the truth. [SPEAKER_03]: The way people get news is changing.

[SPEAKER_03]: It used to be that there were many reporters who would research stories and write articles, but now politicians and famous people share information directly with you on social media and the internet. [SPEAKER_03]: That means you find out things fast, but it's up to you to make sure the information's actually accurate. [SPEAKER_03]: And newsmakers don't always do their part. [SPEAKER_03]: The temptation to manipulate information is strong.

[SPEAKER_03]: They bend the truth to deceive so that they can avoid accountability so that they can advance their agendas. [SPEAKER_03]: When you recognize these agendas, you can sometimes find out what's real. [SPEAKER_03]: And we're at a crossroads where anyone can share anything online, so it's important to sharpen your critical thinking skills. [SPEAKER_03]: Finding that deception before it goes viral is pretty much a survival skill now, and we're going to do it together.

[SPEAKER_03]: Let's get on the spot. [SPEAKER_03]: Hello True Seekers and welcome back to Unspon. [SPEAKER_03]: I'm recording this in June of twenty twenty five and protests are on people's minds as anti-immigration and customs enforcement protests in Los Angeles are spreading around the U.S. [SPEAKER_03]: and the federal government has brought in the National Guard and the U.S. [SPEAKER_03]: Marines.

[SPEAKER_03]: As I'm watching the events unfold, I'm looking at the difference between liberal leaning MSNBC and conservative leaning media outlets in how they cover people taking to the streets to express themselves. [SPEAKER_03]: And you know these kind of public demonstrations serve a purpose to get attention. [SPEAKER_03]: A gathering of angry folks outside your meeting or maybe even blocking the road will get your attention.

[SPEAKER_03]: And sometimes people will create what they hope is a newsworthy event because they hope that it will get coverage and they'll have a chance to use the media to get an audience with legislators who can support them or with other people who can change things. [SPEAKER_03]: But the way you find out about them, it can really shape your perspective of what the purpose of the protest is.

[SPEAKER_03]: So in this week's episode, we're going to learn about protests, about their goals, and about how media coverage shapes them. [SPEAKER_03]: Sound good? [SPEAKER_03]: Let's get on to fun. [SPEAKER_03]: So here's some of why I say protests serve together attention. [SPEAKER_03]: When I used to work at a university in Texas, we found out that a group known for protesting was planning to come and demonstrate in a remote part of the campus at our university.

[SPEAKER_03]: The group was named Westboro Baptist Church, and there were known for staging demonstrations outside of places like Funeral's for military people who died in the line of duty. [SPEAKER_03]: They would set up in public spaces outside of the funeral with signs and shout at people about what they thought was God's opinion about homosexuality. [SPEAKER_03]: And the use of those service members' funerals was controversial and important for some people.

[SPEAKER_03]: And because of that for a while, there were very successful in getting news cameras to come down and do a story about the protest that had the side benefit maybe of carrying their messages. [SPEAKER_03]: I was a journalism teacher and I worked with the student media on campus and we got a message that they were going to be coming and protesting on our campus.

[SPEAKER_03]: The student leaders at that student media decided that somebody coming and trying to make a spectacle didn't really need student news to help them. [SPEAKER_03]: So they did not send a reporter or a photographer. [SPEAKER_03]: And although a group from that church did come and set up for a short time, they didn't get the attention they wanted so they left pretty quickly. [SPEAKER_03]: The goal of a protest is to get attention.

[SPEAKER_03]: And in fact, in some parts of the world, where governments do not listen to what their people are doing, they're needing, disruptive protesting is the only way for people to get what they need. [SPEAKER_03]: And I've seen this in several places where I've been traveling on business so I couldn't get from one place to another in a city because of a protest.

[SPEAKER_03]: This kind of small disruption does get attention, kind of like a strike does, but not all protests have to be disruptive. [SPEAKER_03]: And here in the US last week, we had a whole bunch of good-sized parallel protests all over the country for what was dubbed No Kings Day. [SPEAKER_03]: Suggested that the government doesn't have absolute power and government officials are not above the law.

[SPEAKER_03]: What I'd really like to talk to you about today, though, is how the media reacts to and presents protests, because I've noticed that because of the standard way that the media works, media focuses on things that are not normal. [SPEAKER_03]: It's sometimes a very misleading view of a protest, and I'm not the only one who's noticed this. [SPEAKER_03]: Scholars have been looking at this for quite a while.

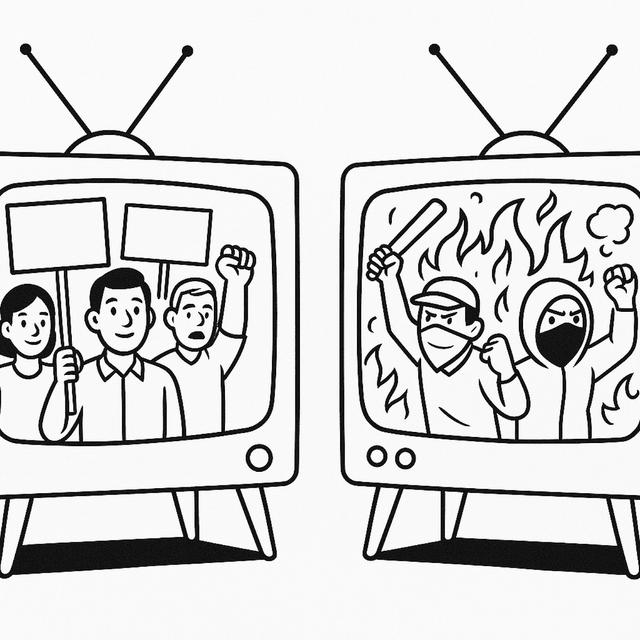

[SPEAKER_03]: You can't look at media coverage of an event and see very different estimates of how many people attended. [SPEAKER_03]: You'll see different ideas of what they were doing, et cetera. [SPEAKER_03]: And you'll also notice that certain protests just look different depending on which news channel you're watching or which website you're reading. [SPEAKER_03]: You can think about the Black Lives Matter's protests in twenty-twenty after George Floyd's death.

[SPEAKER_03]: The media coverage wasn't just reporting events, it was shipping how you thought about it. [SPEAKER_03]: Where those BLM protesters peacefully occupied public spaces of the science, where they were adding thugs who were setting things on fire. [SPEAKER_03]: You could find media depictions that could show both. [SPEAKER_03]: But generally, someone holding a sign is not as eye-catching as someone throwing a Molotov cocktail.

[SPEAKER_03]: So the more dramatic elements in a protest tend to get bigger coverage. [SPEAKER_03]: They're more likely to be run. [SPEAKER_03]: They're more likely to have video. [SPEAKER_03]: And in some cases, a small video clip of an isolated incident will be run again and again and again. [SPEAKER_03]: Sometimes even in a single broadcast and sometimes across several days. [SPEAKER_03]: So whatever is the most dramatic image is the one that's going to be used and reused.

[SPEAKER_03]: And that is in a lot of ways how the media works. [SPEAKER_03]: But it can also give you an extremely distorted image of what is happening. [SPEAKER_03]: Media scholars call this the protest paradigm. [SPEAKER_03]: Essentially, it describes how media outlets often portray protesters negatively. [SPEAKER_03]: They focus on violence or spectacle or confrontation. [SPEAKER_03]: Instead of the thing that people are protesting about, you know, their core messages.

[SPEAKER_03]: So let's look a little closer at those Black Lives Matter protests. [SPEAKER_03]: Researchers Gregory Gontway and Sima Balmick, compared images used by mainstream outlets like CNN and Fox News, to those that ordinary people posted on Twitter. [SPEAKER_03]: mainstream media often chose pictures of violence and chaos, mostly featuring male protesters and rarely showcasing racial diversity in the group.

[SPEAKER_03]: On Twitter, though, citizen journalists painted a much more varied picture, including peaceful moments and highlighting the involvement of women and children. [SPEAKER_03]: So what happens when the media focuses primarily on violent images? [SPEAKER_03]: Entire movements can start looking like they're just really chaotic or filled with a bunch of criminals.

[SPEAKER_03]: People's ask for things in society, whether that's stopping police brutality or stopping shooters in schools, can look like enraged demands. [SPEAKER_03]: And I can lead the audience to associate entire movements with chaos or criminality overshadowing what may be legitimate demands for justice from peaceful protesters.

[SPEAKER_03]: have a listen to this clip from Fox News, where the A secretary Doug Collins is talking about the impact of that uprising in Los Angeles on VA operations. [SPEAKER_00]: Well, see, this is what happens when you get into these discussions all the time marks. [SPEAKER_00]: We talked about the, well, it's the riders and the peaceful riders, which we know they're not peaceful.

[SPEAKER_00]: We see what they're doing, they're throwing stuff at eyes so they're taking it out on their police. [SPEAKER_00]: But yet, what we don't always talk about and what Gavin Newsman and Ali, the mayor that won't talk about, is the impact to the people who are just trying to live their lives. [SPEAKER_00]: Notice the word that Collins used. [SPEAKER_00]: Well, see, this is what happens when you get into these discussions all the time.

[SPEAKER_00]: We talk about the, well, it's the riders and the peaceful riders, which we know they're not peaceful. [SPEAKER_00]: We see what they're doing. [SPEAKER_00]: They're throwing stuff at ice. [SPEAKER_00]: They're taking it out on the police. [SPEAKER_00]: But yet, what we don't always talk about what Gavin Newsman and Ali, the mayor that won't talk about, is the impact to the people who are just trying to live their lives. [SPEAKER_03]: He used the word rioters.

[SPEAKER_03]: Now, by definition, a rioter is someone who's taking part in a violent disturbance. [SPEAKER_03]: And it's interesting because if you watch the clip, the video that's playing while Collins is talking is if people who are in the street and they have clouds of tear gas around them. [SPEAKER_03]: People generally do not tear gas themselves, so it's likely that the only violence that's actually being depicted is being caused by law enforcement. [SPEAKER_03]: Here's another example.

[SPEAKER_03]: This will be the White House Press Secretary Carol and Levitt, answering a question about who the government believes is paying demonstrators in Los Angeles. [SPEAKER_03]: And just to be clear, there is no evidence that demonstrators were paid by anybody. [SPEAKER_07]: You will see boxes and boxes of very professionalized masks and rioting equipment being dropped off for these protesters.

[SPEAKER_07]: So it's a good question the president is raising in one we are looking into about who is funding these insurrectionists and these rioters and these protesters and these illegal criminals. [SPEAKER_03]: Now, Levitt's language is more complex. [SPEAKER_03]: She refers to rioters and rioting equipment, whatever that is, as well as protesters, insurrectionists, and illegal criminals.

[SPEAKER_03]: This clip was at a national press conference, but it was published by local new station of Minneapolis. [SPEAKER_03]: And I'd like to play one more example for you. [SPEAKER_04]: For about five or about five or six hours a year you can hear this line. [SPEAKER_04]: It was absolutely peaceful. [SPEAKER_04]: The whole test is just around the city. [SPEAKER_04]: The LAPD was very heads off, they let. [SPEAKER_04]: A rally happens about twenty thousand people.

[SPEAKER_04]: Then people march around the city. [SPEAKER_04]: The LAPD left them doing. [SPEAKER_04]: And about two hours ago, a little bit more, they started to talk about the federal building, which is that building over the last year by last year. [SPEAKER_04]: Right. [SPEAKER_04]: About twenty minutes ago, at least. [SPEAKER_04]: This is from ABC's National News Broadcast and their reporter's name is Matt Gutman.

[SPEAKER_04]: He's reporting on a day of demonstration followed by police moving in to remove protesters. [SPEAKER_03]: Now the network made a choice here. [SPEAKER_03]: As you can hear from the very noisy background audio, they stationed the reporter in the middle of a crowd of protesters and collected the sound there.

[SPEAKER_03]: And that was a choice that they made, because they could have had the reporter walk to a less busy area and do a stand-up and then run the background video without sound. [SPEAKER_03]: The reporter did refer to the gathered crowd as protesters, but because of having the natural sound of the people yelling around him, it made things seem very emotional. [SPEAKER_03]: Researchers Danielle Brown and Rachel Moral did some experiments to show how media framing affects public opinion.

[SPEAKER_03]: So let me ask you, do you think it would affect the audience if they read an article describing a protest as a quote riot versus one describing it as a legitimate quote debate about civil rights? [SPEAKER_03]: In their study, they found that audiences reading about a debate, even it was describing the same event, felt more supportive of protesters and more critical of police.

[SPEAKER_03]: But when the coverage emphasized riots or confrontations, that support for the protesters dropped dramatically. [SPEAKER_03]: Again, articles describing the same event. [SPEAKER_03]: So true seekers, this is powerful stuff. [SPEAKER_03]: It highlights the responsibility that media has in shaving public conversations around social justice. [SPEAKER_03]: It turns out that this protest paradigm is pretty common in coverage of protests around the world.

[SPEAKER_03]: Now, again, I think some of this is just because of the nature of what news is. [SPEAKER_03]: You know, you can imagine for a second that there was a town that was hit by a tornado. [SPEAKER_03]: This actually happened to me when I lived in Texas.

[SPEAKER_03]: There was a tornado very close to where I live, so much so that the TV station we were listening to for news coverage, which was less than ten miles from my house, went off the air after the very last thing you heard was the weather guy yelling, everybody getting the closet right now. [SPEAKER_03]: And tornadoes can be very destructive, but they're also pretty selective.

[SPEAKER_03]: So our house was completely fine, but our neighbor's house was a more dramatic picture because the twister had taken their trampoline from their backyard and sent it to the roof of their house. [SPEAKER_03]: If you're a news photographer covering the storm, which picture seems like news, my perfectly fine house that looked at the same as it did before the storm, or the house of the tornado driven trampoline through the roof.

[SPEAKER_03]: News is usually what's not normal because what's normal is just not interesting. [SPEAKER_03]: So when journalists prepare stories and images, they tend to look for that conflict or that drama frame. [SPEAKER_03]: Now there's other factors as well. [SPEAKER_03]: So let's visit Brazil in twenty fifteen. [SPEAKER_03]: Where some were out at another study and she looked at right wing protests against the president at the time, Dilma Rousseff.

[SPEAKER_03]: And she found that Brazilian-made outlets presented this protest positively because their goals matched with powerful political interests. [SPEAKER_03]: A lot of protest reports highlight classes with authorities, but these Brazilian protests received coverage emphasizing their peacefulness and unity. [SPEAKER_03]: So the results of this was that the public became more sympathetic and the protesters seemed more legitimate.

[SPEAKER_03]: Some test protest actions are designed to win sympathy. [SPEAKER_03]: So for example, there's actually a whole museum of protest and they have a website. [SPEAKER_03]: And one tactic that they said was to actually take your clothes off during the protest calling it a disrobing protest. [SPEAKER_03]: And it highlights the vulnerability of the protesters. [SPEAKER_03]: This was done by Irish women who wanted access to male only areas in the nineteen forties.

[SPEAKER_03]: It was done by Indian women in two thousand and four is they were seeking justice for rape victims. [SPEAKER_03]: Hending riot police flowers has been another tactic. [SPEAKER_03]: And in the preparation materials for last week's Noose King's marches, there was advice that circulated online that if there was any aggression protesters should link arms and sink to the ground, emphasizing the peaceful nature of what they were doing.

[SPEAKER_03]: And that seemed like it could be a good strategy as nudity or flowers are in themselves unusual. [SPEAKER_03]: And so that could attract those cameras you're trying to get the attention from. [SPEAKER_03]: But there is a risk though that something that has more conflict or more violence was going to pull the attention away.

[SPEAKER_03]: So for example, in Charlottesville, Virginia, there were unite the right protests where torch-braring protesters shouted terrible things as they walked through Charlottesville, and that were followed by counter-protests in August of year, and one of the groups that was there included a group of clergy who were wearing their liturgical outfits right, their colorful robes and stoles and things like that.

[SPEAKER_03]: And I think the hope there was that that would show peaceful demonstration for the cameras. [SPEAKER_03]: But you probably don't remember that that happened because a protestor named Heather Hyer was actually killed when a man drove his car through the crowd in anger. [SPEAKER_03]: The violence and conflict frames became how the protest was remembered. [SPEAKER_03]: The relationship between power and protest coverage is true in a lot of places.

[SPEAKER_03]: So in a global study, researchers Summer Harlow and her colleagues examined thousands of protest-related articles that were shared on social media. [SPEAKER_03]: And they found that what gets attention online often involves the dramatic or sensational angles. [SPEAKER_03]: And that reinforces existing biases or stereotypes regardless of what's actually happening in the protest.

[SPEAKER_03]: Okay, I need to take a quick break, but when I come back we're going to look at some more real-world examples of protest coverage and how it is directly influenced if protest movements succeed or fail. [SPEAKER_03]: I'll be right back. [SPEAKER_03]: Welcome back.

[SPEAKER_03]: Okay, so we've talked about that protest paradigm where the media covers a protest as an event and a conflict between the protesters and the establishment rather than digging into the situations that may be inspired the protest. [SPEAKER_03]: And we can kind of see this as an example of media framing where the media tells the audience not just what's happening, but what the audience should think about it based on the way that the media presents the message.

[SPEAKER_03]: So we'll bring all this together with a specific real-world event, those George Floyd protests. [SPEAKER_03]: Researchers Holly Coward and her team looked at more than five hundred tweets from US mainstream media outlets, and they noticed something intriguing. [SPEAKER_03]: The coverage actually shifted from traditional law and order frames toward highlighting civil liberties and protestor signs, and this let protesters communicate their messages directly to the public.

[SPEAKER_03]: And they noted that this was a really big departure from the way protesters typically covered. [SPEAKER_03]: And you know, it's just maybe the media can adapt or evolve or even improve. [SPEAKER_03]: Imagine that you're in Birmingham, Alabama in nineteen sixty three. [SPEAKER_03]: It's hot. [SPEAKER_03]: It's tense. [SPEAKER_03]: And your mon crowds were gathered downtown. [SPEAKER_03]: You're hearing those songs from the crowd, because it's good Friday.

[SPEAKER_03]: And Reverend's Fred L. Shuddlesworth, Ralph David Abernathy, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. [SPEAKER_03]: led a march to City Hall in Birmingham on that day. [SPEAKER_03]: That march was organized by the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as a part of their Birmingham campaign to desegregate businesses parks and hiring in that city.

[SPEAKER_03]: The groups had requested a permit to parade or demonstrate, but local government had denied it. [SPEAKER_03]: Aberna thinking were actually arrested for parading without a permit, as well as fifty other protesters who ranged in age from fifteen to eighty-one. [SPEAKER_03]: And King's arrest sealed his status as one of the most important leaders in the American Civil Rights Movement.

[SPEAKER_03]: In May of that year, at what was dubbed the Children's March, the response from the government turned violent as official sprayed participants with high-powered fire hoses and set police dogs on them. [SPEAKER_03]: The sprayfulness fire hoses was powerful enough to strip the bark off of trees, and video news from the time shows it knocking demonstrators including children and teenagers to the ground. [SPEAKER_03]: This was front page news.

[SPEAKER_03]: But check out how it was covered. [SPEAKER_03]: The New York Times headline read, dogs and hoses repulsed Negroes at Birmingham. [SPEAKER_03]: Notice that the frame is the government response, not the protest itself. [SPEAKER_03]: And this was one of many demonstrations for civil rights at the time, including a march on Washington DC in August of that year.

[SPEAKER_03]: Other Thomas Jackson wrote a book about King Jr., and noted that the media mostly covered what he called, quote, the violence that did not happen. [SPEAKER_03]: A headline about that event from the Times said police precautions and festive spirit of capital keep disorders at a minimum. [SPEAKER_03]: Notice how this headline, once again, focuses on the government response not the issues of the protesters. [SPEAKER_03]: And we can consider one more example.

[SPEAKER_03]: We can picture Zucati Park, a private park in New York City in September of twenty eleven. [SPEAKER_03]: It's the fall, and you can hear on the breezes, the soft home of discussions among groups of students, unemployed workers, activists, all gathered beneath tents where they had been living in the park. [SPEAKER_03]: And there's signs that read things like, we are the ninety-nine percent.

[SPEAKER_03]: Early news reports kind of thoughtfully looked at occupied movements critique of economic disparity. [SPEAKER_03]: Listen to the start of this New York post story. [SPEAKER_01]: Music, signs, makeshift beds filled Zacoodle Park as two hundred protesters took a stand against corporate greed in the face of America's recession. [SPEAKER_08]: We're putting our bodies in the street, and we're mobilizing, and we're going to make the government afraid of us for a change. [SPEAKER_08]: OK.

[SPEAKER_01]: OK. [SPEAKER_01]: OK. [SPEAKER_01]: Pro-Testors call the movement Occupy Wall Street and some have camped out since September, seventeenth. [SPEAKER_05]: If you feel it in your heart, no matter what your age or place in life, you should be out here. [SPEAKER_03]: As the weeks pass, though, the story's changed. [SPEAKER_03]: Gradually, the cover started shifting to the protest paradigm frame. [SPEAKER_03]: After about a month, listen to the CBS news report.

[SPEAKER_00]: Third confrontation with police today was averted, Jim. [SPEAKER_06]: Scott, the senior tonight, is just like it's been for most of the last four weeks, mostly common civil. [SPEAKER_06]: But for a few hours this morning, it seemed like things were about to escalate and boil over. [SPEAKER_06]: Just before dawn, the crowd of demonstrators swelled in this privately owned park to finally daring the police to evict them.

[SPEAKER_06]: The park's owner broke field properties had asked police to clear it out so it could be clean. [SPEAKER_06]: The protesters thought it was a ruse to remove them for good. [SPEAKER_06]: The police warned that at seven o'clock this morning, they were coming in. [SPEAKER_04]: Sure, it was a showdown. [SPEAKER_04]: The city made it into a showdown. [SPEAKER_03]: It's important to realize that nothing actually happened on that morning.

[SPEAKER_03]: But the story that the news told about what could have happened went back to that original frame of government versus disruptors. [SPEAKER_03]: Ultimately, media attention focuses less on protesters' messages and more on the disruptions that protests cause. [SPEAKER_03]: stories about inequality and corporate greed and erosion of middle-class security. [SPEAKER_03]: They get kind of muddled by a sensational framing of protesters and nuisance.

[SPEAKER_03]: And, you know, as we've seen from the research, this can cause public support to go down because media portrayals really influence whether a social movement seems to be legitimate or not. [SPEAKER_03]: And so it goes.

[SPEAKER_03]: When students walked out of school in support of gun regulations after a student at a high school in Parkland, Florida, killed many of his classmates, the stories were about prominent figures claiming that the students who walked out were so-called crisis actors just trying to get attention for themselves.

[SPEAKER_03]: We also saw this a little bit with the coverage of last week's No Kings protests, where the framing in a lot of new stories was either one about how big the crowd was, or a conflict frame putting those protests against the turnout for a military parade in Washington DC. [SPEAKER_03]: So here's the challenge for you, Altru, Seekers. [SPEAKER_03]: Next time you see protest coverage, ask yourself, you know, number one, what kind of images are they using to dominate the coverage?

[SPEAKER_03]: Number two, whose voices are being featured and whose voices are missing? [SPEAKER_03]: And number three, does this coverage kind of bring up any emotions in you and if so, what are they? [SPEAKER_03]: And why might that be? [SPEAKER_03]: Alright, thanks for tuning into Unspon. [SPEAKER_03]: Stay sharp, everyone. [SPEAKER_03]: Thanks for getting unspunned with me this week.

[SPEAKER_03]: Unspun is a production of me, Amanda Sturgeon, and is a proud member of the MSW Media Family of podcasts. [SPEAKER_03]: Some of your thoughts and ideas about trickery and the news on Gmail, at the unspunpodcast at Gmail.com. [SPEAKER_03]: I even write back. [SPEAKER_03]: And find this episode, show notes, and more information at the unspawnpodcast.substack.com. [SPEAKER_03]: Want to learn more and get smarter?

[SPEAKER_03]: Check out my book, detecting deception tools to fight fake news, which is available on Amazon or your favorite online bookseller. [SPEAKER_03]: And until next time, stay sharp, everyone.