School of Humans. This episode discusses historical events that include physical and sexual abuse against children. Like the rest of the South, Alabama is a study in contradictions, a region known for both warm hospitality and gross and justice, swelling with pride and stricken by conscience. It's a tangle of racial, economic, and geographic disparities. Lots of America can be like this, sure,

but Alabama's complication is legendary. On one hand, the state is deeply conservative, teaming with good old boys and Confederate flags. While most of the nation is celebrating the Martin Luther King Holiday each January, Alabama celebrates King Lee Day instead, a joint observation of Martin Luther King and Robert E. Lee. So you'd be forgiven for thinking that a state with this much of a racist history would be pretty white.

But Alabama is not a white state. I say this as a Black Southerner myself, For me and my family and over half of black people in America, the South is home Over a quarter of Alabama's residents are black, almost twice the national average, and Alabama has the fifth

highest black population of any state in the country. In the nineteen sixties, the state's black population was even larger, but you wouldn't have known that looking at the crowd that surrounded Alabama's capital on January fourteenth, nineteen sixty three, to see George Wallace sworn in as governor after an unsuccessful run as a moderate in nineteen fifty eight. Wallace triumphed four years later, in part by promising never to integrate the state. It was during this inauguration speech that

Wallace made a defining statement of the era. Bag White people have maintained power in Alabama, not just back then, but today as well, thanks to the law. It's easy to think of the law as being an objectively moral force, one that is overwhelmingly fair and equal. But the law isn't objective, nor is justice blind, and the rule of law is not about fairness or consistency. It's about power. The law mutates and remolds itself to serve those who enforce it, who make it, and who benefit from it.

Everyone else is at its mercy, and no one knows that more than black people in Alabama. I say that to remind you that the children were talking about in this po podcast were technically legally criminals. The law had made that determination and so that's what they were, juvenile delinquents, Negro lawbreakers. Never mind that the laws that they were breaking were laws designed for them to break, implemented so

that the state could deem them criminals. These were children, often as young as ten or eleven years old, suffering trauma from being separated from their loved ones, taken from their families and handed over to the state. They were children, but to the state of Alabama, they were criminals all the same. That is the Alabama that Lonnie Holly, Jenny Knox, Johnny Bodley, and Mary Stevens, as well as countless other

young black children grew up in. We have viewed with dismay the tragically slow pace of the Negros progress or a full emancipation the state of Alabama, enforced by the demogoguery of the racist courses in the machinery of government. These incidents in Alabama were caused by outsiders who came to this state seeking trouble. I felt that I was not being treated right then that I had a right to retain the sea that I had taken as a

passenger on the bus. The federal officers are armed with a proclamation from President Kennedy, urging the governor to end his efforts to prevent two Negro students from registering at the university who are committed to a worldwide struggle to promote and protect the rights of all who wish to be free. You are ordered to disperse, go home, or go to your church. This march will not confett. Montgomery, Alabama, in the sixties was the most segregated place on the planet.

That's Denny Abbott, a former juvenile probation officer. If you look up Mount Meg's, one of the first things that pops up is a book called They Had No Voice, written by Denny. In it, he tells the story of the eleven years he spent working for Montgomery County Juvenile Justice System as a probation officer. He's a big part of our story, as you'll find out later. When telling us about his childhood, he told us that his father was an out and out racist. I heard the in

word every day from him. In fact, I think my fathers don't remember the clan quite frankly, and growing up, Denny lived a very segregated life. Elementary school, middle school, high school, in college. I never went to school with a black person, not once. Didn't know the name of a black person until I started working after I graduated from college, so I really had no information about the

black community. Everything was rab After graduating from Huntingdon College in nineteen sixty one, didn't he found himself married and broke. He was just twenty one and he needed a job, any job. I found out about an opening as a probation officer with a montgomer Juvenile court. His title was actually boys Counselor and interesting and actually what I find

kind of disturbing euphemism for probation officer. I was one of like seven or eight probation officers there, and just a few weeks into his job, he had to drive a black child to Mount Meg's for the first time. What I saw driving up to the institution were black kids working in the fields, and they were wearing army fatigue so well cast off army surplus pants and shirts that were much too large. They had to roll them up.

Most of the kids were barefooted and that's what they did from sun up to sundown, work in the fields. And then I got to see a couple of the buildings and they were all and increpit. I do remember that there was a train for a waste, human waste that was just outside the door and window that was open, and just the conditions were hardle That was Denny's first glimpse of Mount Meg's, a place he eventually drove hundreds of kids to a place he would come to call

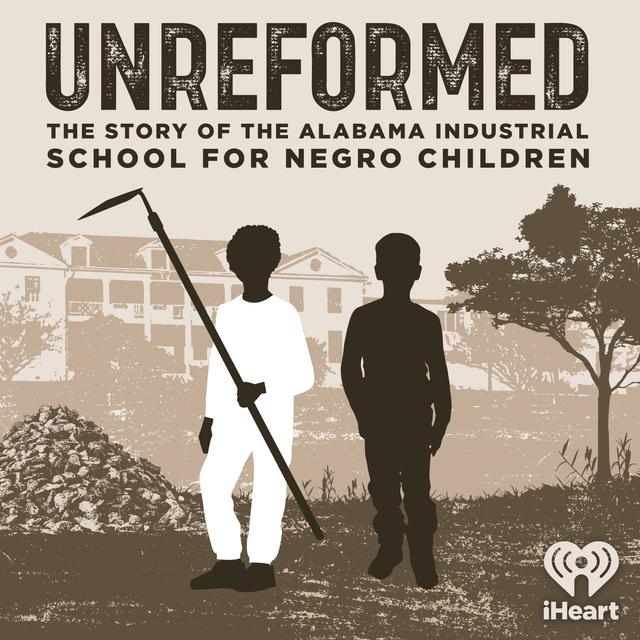

a slave camp. I'm Josie Duffie Rice, and this is unreformed the Story of the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, Episode two, The Arrival. If you were a kid in nineteen sixties Alabama and you were accused of breaking the law in some way, one of two things would probably happen. If you were white and had the money and resources, you'd probably get to go home, no charges, no punishment. But if you were one of the unlucky ones, you

were sent to one of three industrial schools. There were two near Birmingham, one for white boys and one for white girls, but all the black kids, boys and girls were sent to the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, otherwise known as Mount Meg's. And in some cases you could be sent to Mount Megs even when it wasn't clear that you'd broken any law. If they ran away

from home, the juvenile court would exercise jurisdiction. If they were incorrigible, if they didn't listen to their parents, they could be sent to the juvenile court. That's Barry Feld. He's a Centennial Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Minnesota Law School. In addition, the children who were abused or neglected or dependent through no fault of their own but because of their family circumstances would also end

up in juvenile court. Some of these kids were sentenced to time at Mountmegs, but other kids, they didn't even see a judge. They just got sent straight there, no formal charges, no clear sentence. Once we get into the judges chamber, he said, ma'am, I'm sentence in you a year and six months to the Mountmegs in Dukeshire school. Huh what why? What? I do you know? I didn't do anything and I just cried and cried and cried and cried because I didn't understand. I don't know. That's

Jenny Knox. Jenny was born in October in nineteen fifty two. She adored her mother, but Leona Montgomery had her challenges. She had many children, some of whom Jenny had no connection to, mostly Jenny had a relationship with her older sisters, Geraldine and Ernestine, who were close in age to her. She lived with the two of them, her mother, her three younger half siblings, and their father, John Montgomery Senior,

the only father that Jenny ever knew. Life with John as their father was comfortable and the family lived in a nice home. But we didn't have to worry too much about anything when she was married. But when Jenny was a young girl, John Montgomery was shipped off or yet another military tour abroad, and she and her siblings lived alone with their mother, alcoholic who struggled to parent. Something had to give. She started drinking and things stought happening.

I just say life stowed happening in the process of life happening. To her, it was at our experience as children. When Jenny was around twelve, she and her younger siblings were placed in a foster home, and then a different one, and then yet a different one. Eventually, Jenny's aunt, Willie G. Robinson became their legal guardian. Being taken in by actual family seems like it would have been a relief, but Jenny hated living with Aunt Willie. She made them work

in the fields picking peas and cotton. She isolated them from family and friends. She controlled every aspect of their lives. I really didn't want to stay with their you know, because I didn't. I didn't feel like I was being treated right. As a matter of fact, I didn't feel like any of us was treated right. So Jenny ran away. She left Aunt Willie's house with a single goal in mind. I just wanted to be with my mom. Nothing else

really mattered to me like being with my mom. There was nobody greater, you know, a better knew how to take care of me and love me like my mom. Jenny ended up staying with another aunt, who told Jenny she was welcome as long as she did her choices and went to school. The arrangement was working out well until one day a school staff member came to Jenny's class and summoned her to the principal's office. Jenny was devastated when she saw who was waiting for her. She

was there, Oh my god, it was Aunt Willie. Even though Jenny was consistently attending school, and even though she was much happier staying with her other aunt, the judge ruled that Jenny running away from her appointed guardian, Aunt Willie, was an offense punishable by time served at Mount Meg's. I wasn't out drinking, getting drunk, being loose in the streets or whatever. I had class, not even think about no boyfriend and all that different kind of stuff. But

I didn't understand it's still about this meat. So when Jenny was around thirteen, she was sentenced to eighteen months at Mount Meg's. If you're wondering why these kids didn't push back or appeal their sentences, the answer is that they couldn't not back then. At least they weren't entitled to lawyers. Children didn't really have any legal rights at all. Until just fifty five years ago, American kids were being carted off to juvenile attention without first being afforded any

procedural rights. Rights that for kids like Jenny Knox could have made a huge difference. And I have a lawyer. I don't know anything about the lawyer. I don't know I needed one. I was awarded with State Department Children's Services had taken us from my mom several times. My mom was still having children. Mary Stevens, who met in her garden an episode one, has a similar story to Jenny. My mom was needing me to work help pick continent

stuff for her to feed the children. I had to do that, so I was missing so many days to school and stuff and having to work that it just got to wear. I didn't want to go to school anymore because I was so far behind and everything. You know, I just didn't want to go. Eventually, not going to school led to serious consequences. We moved to Scottsboro, Alabama, where I had skipped school one day and I got

caught why shrotzy I went to June. Somehow they decided that I was going to go to Montgomery, and I didn't know where I was going at the time. In fact, Mary thought this moved to Montgomery might be good news. She thought she might be getting a family again. I thought I was going to be adopted because one of my brothers was adopted. In nineteen sixty seven, at age thirteen, Mary was sent to Mount Meg's for truancy. This is

part of the story that haunts me. Like Jenny and Lonnie, all Mary really wanted was her mother, and instead she was functionally sent to a juvenile prison, a place where love and care were absent. I believe, Oh, I believe. Across Alabama, Mount Megs was used as a boogeyman, essentially to scare kids into good behavior. They say, you keep being bad, You're going to Mount Megs. That's Johnny Bodley, who you met in episode one. He's the professional musician

who lives in Selma. Growing up, Johnny heard stories about Mount Meg's firsthand from his sister, who also went there, but her horror stories about the place weren't enough to keep Johnny out of there himself. Back then, when the local paper mentioned Mount Meg's, it was always because of a kid who was sent there after committing a more serious crime. Lots of stories about theft, and even some kids accused of attempted rape or assault. The paper only

ever mentioned those small minority of kids. But like Lonnie, Mary and Jenny, there were many more kids who were sent to Mount Meg's for tiny in fractions or really for being poor and black. But of the four of them, Johnny might be the closest to what the system would consider a quote unquote delinquent today. He was caught by the police in nineteen sixty seven. I ain't sitting in the city jail for three months and they shift me

to Mount Megs. On July twenty second, fifteen birthday, Johnny, Lonnie, Mary and Jenny and everyone who came to Mount Megs got there the same way, driving down a long road that led to the school. Everyone we talked to you remembered that drive and how they had no idea what awaited them. Mount Mags is about twenty miles east of

Montgomery and two hours south of Birmingham. In the nineteen sixties, the kids were driven there by a juven no probation officer, someone like Denny, and often they were handcuffed in the back of the car. Lonnie, who came from Birmingham, probably took the newly constructed State Highway sixty five, which follows the Coosa River. On the edge of the highway, there

were farmhouses and fields rolling by. Depending on where they were coming from, it could take hours to get there, heading away from the life they knew, with no idea what awaited them. But eventually they'd reached the road to Mount Meg's. It was scary just to go down that roll, Dan, You ride slowly down this two lines street, pale trees on both sides. You're riding slowly. None of us know where where we was going the gate. First of all,

taking that long ride two mountain mags. You're nervous, you don't know what to expect, your mind running crazy or whatever. You see this big old white house which is the girl's home. This big building, a big long front ports. It was a pretty building, but it look kind of like a plantation house. And then when you get on up to the building, you see young ladies out in the field, open field, and they was literally bent over, you know, with their hands picking, pulling grass. And then

let me know that this is a horrible vision. The boys side was further on down the road from us. We go through this gate where the gatekeeper were vehicle stopped. He gives him man and signing man. Then we moved slowly on down that road. Then you start seeing all of these cottages, rick buildings with bars and things on the windows, just awful looking buildings, block up buildings called to see Cottie J cottage D. I've seen all these boys. It's out on the yard just walking around, just just

doing nothing. You know. All of them looked deadly, all of them looked mean. I remember the rock pile. It's off. I mean, it's like in this big, this big yard, and all of this dirt and all these big, these big square rocks painted white. The pile of white rocks looked ominous, a dramatic but kind of curious centerpiece on the flat pastoral landscape that Lonnie and Johnny came to

understand all too well. When Lonnie arrived, the hard pulled up to this old big house on the campus, and out came the superintendent, Elias Brown Holloway, otherwise known as EB. Mister Holloway came out, and he was huge and big, and he would stand up and look at all of us, and then from that he tells us about the place and tells us that we should never try to run away. There is no escaped in now. Please, Lonnie still shutters

at the memory of Holloway. You may remember that just days before this, Lonnie and some other boys had tried to escape from Birmingham Jail. But the minute he saw Holloway, he knew that escaping from this place would be much harder. After arriving boys were given standard issue military fatigues. This was the only clothing that they had. It's the same thing that Denny saw the kids wearing when he showed

up to Mount Meg's for the first time. You take all value surveying cloth, you turn now me in, you turn in any properties or ended tying your head in your pockets. The campus had several buildings, a chapel, a barn, a cannery, a nurse's station that was almost always empty, in a schoolroom that a lot of kids never saw the inside of. The boys slept in buildings called cottages. Johnny was at first assigned a cottage d, a residence known for being unlocked down twenty four hours a day.

The cottages were overseen by counselors, and during Lonnie's time at Mount Meg's he remembers one of the councilors supervising his cottage had been convicted of serious violent crimes, and the cottages were packed full of kids. In some years, three kids slept on one cot The barely stuffed mattresses reeked of urine. The conditions and facilities were disgusting to the point of hazardous. Mount Meg's was virtually unlivable. There was an open sewer full of fieces and trash that

became a cesspool for mosquitos. The outhouse was just a long board with multiple holes cut out of it. In the buildings, dilapidated and poorly constructed, were extreme fire hazards. For at least one stretch of time, there was no clean water at the facility at all. The kids never had enough to eat, and what they had was barely edible. After all, the kitchen was full of roaches and other vermin,

but they were so hungry they'd eat anything. In one story, when a kid vomited all over his food, another boy was so hungry that he ate it. One survivor said he often saw boys pick corn out of kalmaneure to eat. The kids were assigned jobs, manual labor that they had to do to maintain them Mount Meg's campus. There were chores like working in the kitchen or milking the thirty five cows, but all of them were expected to work in the fields. Mount Meg's was surrounded by miles of farmland.

There were fifteen hundred acres. They were filled with fruit trees, row upon row of vegetables, but mostly cotton. It looked at dislike slavery. Can I mean? They would land us up in the morning and all the boys would have to hold it holes up in the air, and when we get ready to go to something that we would sea it would say chopped down. All of these boys would madge to a field about fast six seven miles away to work. Sometime. They ran to the field every

day from dawn until dusk. There they were black children out in the alle Obama fields picking cotton. These kids were being worked to the absolute bone. These were kids, usually from cities like Birmingham or Montgomery. They were told this was training, but training for what, and even for the kids that did have farming experience, was close to impossible to pick that much cotton every single day. When I first got day, I didn't know nothing about picking cotton.

I'll just pull the whole stalcon everything. After filling up large sacks with cotton, a truck would drive by with a way station, making sure that the kids had met their quotas. One time, Lonnie and some other boys tried to outsmart the scale by adding stones to the bottom of the bag. It was stupid for us to do that. That led to serious punishment, punishment that the kids at Mount Meg's were all too familiar with. If you didn't pick a hundred pounds or caught in today, I don't

care how old you would, they would beat you. They would punish you if you didn't pick a certain amount of watermelons, if you didn't pick a certain amount of cucumbers. In Mount Maigs, they would punish you. If you was running to the field and you got sick, they would

punish you for that, quote unquote. Discipline at Mount Meg's was relentless, and you could get punished for almost nothing, or for things completely out of your control, like this one time that Johnny and some other boys were riding in the front seat of a truck after the fields when the driver of the car suddenly slammed on the brakes. The boys were thrown forward and the windshield was shattered, and mister Glover took each boy down out of the trunk and beat him right there, as if it was

our fault. Mister Glover was the man who oversaw the boys work, watch their every move in the fields. Mister Glove was an older man. Whatever part of the military that he was in had lamed him because he mostly sit down everywhere he went. Despite his disability, mister Glover had a reputation for beating kids with a particular intensity. John Henry, but that's the name of his stick, and John Henry the oak stick isn't mister Glover's only signature.

Mister Glover usually sit in his chair and beat you, and you dan hire on the ground. He would beat you while he's sitting in his chair. For the boys who failed to complete all their cotton picking on his watch, mister Glover has an especially disturbing punishment. He would take his oak stick and drill a hole in the ground. He would say, you see that hole in the ground, boy, and you would have to say, yes, I'm mister Glover. He was here. Put you your private part in it.

Put your dick in the hole, not literally pull yourself out of the clothes. What deathway you laid on top for that whole and he began to whoop you. Every time he whoop you, he hits you, and then here a grunt with the stick. And Danny'll keep on hitting you with the stick each time, and he grunt, and your fast swell up and pretty soon you walking with a limp. That's just how bad Mountmaids were. There were a number of other adults who ran the facility in

the nineteen sixties. Mister Reddy was another infamous punisher mister Reddy. He was a shell shocked person. Man. He was wow we call him wild ch out like God damn it. He would cross all the time. If he caught you doing something, God damn it, you want to be a fucking bullet, don't you here? A run over? And just stopped beating on you and beat on you and beat on you and beat on you until he felt that he was satisfied. But it wasn't just the staff that

the boys had to look out for. In an essay about his experience at Mount Meg's, Johnny wrote that on the first night there, he stayed awake until morning for fear of being sexually assaulted. And not just by the staff, but by the other boys. You know, all of them look deadly, all of them trying to put fearing you. For Johnny, it's impossible to talk about Mount Meg's without touching upon the rampant sexual abuse that openly took place.

I mean, boys got raped all the time in Mount Megs, and if a boy reported to a counselor that they'd been assaulted, nothing happened. So for blood of them, did they got raped? They would do nothing a bad day. Boys would often stick together in groups based on where they were from. All the Birmingham Boys together Montgomery Boys. When Johnny was there, there were just a couple other boys from Selma, and Johnny quickly learned that even among

those groups there were divisions. There were guys known as scrubs and there were guys known as ikes. Ikes were tough. Scrubs were sort of like the suckers. Many of the Ikes become charge boys, meaning it becomes their job to keep their peers in line. But even though they're all the same age, the charge boys have a lot of power over the others. All they had to say that you left from Cotton when your rope, and they would

take you up to the overseer of mister Glover. The other thing about Mount Mags is that it was a school without any schooling. None of the boys can recount getting a real education there or taking any real classes. It was a labor farm basically. The girls they seem to have some instruction, but not much. Miss Alexander was our weaken night supervisor. I think Harris was fun was I was so in teacher Miss Wright for cosmetology. Mister Dubos was over the feet. That was Jenny. You can

hear just how worked up she is. Even when she's just talking about who was on staff. It's still difficult for her to talk about Mount Meg's. As she recalled her experience there, she cried and cried. When Jenny first arrived, she was taken to the dining hall, everybody together around the wall that you introduced me to the stabs in the ladies and and make you undressed in front of everybody. The staff forced the new girls to bend over naked

and spread their legs for inspection. They said it was for safety, but the girls suspected the real reason was humiliation, to make sure that they knew their place. It affects your privacy, it the grady. Nothing like this had ever happened to Jenny before, and even now, sixty years later, it still haunts her. And that was just day one. It was only the beginning. On the girl's side. They all supped in one dormitory, that big white building that

looked like a plantation house. You can't talk about Mount Meg's in the nineteen sixties without talking about Fanny B. Matthews, the girl's matron. When Mary first arrived at Mount Meg's, though she thought she was safe because I was relieved, because everybody was my complation, and you know that Patty was going to be okay. Everyone who worked or was locked up at Mount Meg's was black. When she first arrived.

This provided a false sense of security to Mary, and she thought she'd been brought to Mount Meg's to be adopted. And when we got there in the driveway and went in, I met my fan to b Matthews, and she greeted me and I asked, Gressa, are you gonna adopt me? I did, and I was there to be get dapped. I didn't know, but Fanny Matthews was no mother to those girls. Missus Matthews was a tall, middle aged black woman who wore a wavy cropped salt and pepper wig.

She was the mastermind of the complex system of psychological and physical punishments she and her staff dolled out to the girls. She had a very strong voice, very strong voice. She didn't have to raise this. She was loud her demeanor, voice and facial expressions, and her walk was fierce. And she always carried a thick, great wooden paddle in her hand, and she would carry that paddle in a poton in

a purse on her shoulder. The paddle was a constant threat and reminder that Fanny Mathews would not hesitate to beat any student. And I've gotten in hitting in the head by miss Matthews several times with these with this baton. Been over and give her a real hump in your back, touch your toes and she comes down on your back as hard as she can, but every ounce of strength in her. And when you do, it feels like you just went through a shop treatment because it hurts that bad.

And I feel like you're going through the floor when she hits you like that. Danny Matthews was relentless. If she heard any girls making noise at night, she'd line up everyone in the hallway, going down the line and hitting girls in the head with that baton. As a punishment, Jenny had to manually dry clothes and sheets, meaning she

had to stand up all night and shake them dry. Mostly, Mount Meg's was a torture sight, a place where children just endured unbelievable abuse, but there were some good moments, some moments when the kids could feel like they were actual children and not inmates. There were a couple of extracurricular activities that Jenny got involved in that did become a part of the choir out there. I became a cheerleader. While I was out there, she even met a boy

nicknamed Chick. Chick was fifteen years old when he and Jenny met at Mount Meg's. He was serving time down the road on the boy's side, and on the rare occasion that it was his job to drive the tractor near the fields where the girls lived, he would get a chance to see them. I think Chick used to always come to the girls home and you know, drive attractors, and you know, I guess he got turned on by seeing me and wanted to know who I word. Their

court ship was sweet, innocent. We just slipped letters to one another, and if we was caught slipping letters to each other, we would get in trouble. But these few opportunities to be normal American teenagers were brief. There were some good things that went on. They didn't last long, but there were some good things that I was in the choir, you know, I was on the football team, was a kitchen boy, worked in the kitchen, and all

of those things were privileged positions. No, but as I said, it was David brutal and if you made it out of laugh, he was blessed. You may be wondering how anyone got out of Mount Meg's alive, and the truth is that many didn't, or at least that's the consensus. We don't have records that tell us just how many kids died because of abuse or starvation or being worked to death. But there were kids who disappeared. And there are memories of children who were beaten within an inch

of their life and then never seen again. And they have him a couple of times. We know that they mout they had to die, they ain't. No amulans came down through them. Some even have memories of a makeshift graveyard. When you're a rabbit Mount Me, you'll see these graves over to the side and you don't know what's up. But a lot of boys didn't even make it out of Mount Me and they said that was not such a graveyard. But I think that was the cover of

because that mouth they have been. And of course all of this, the beatings, the abuse, the sexual assault, the cotton quotas, the strip search, the starvation, the deaths, the graveyard, the infinite never ending punishments were condoned, if not outright encouraged by the school's superintendent, Eb Holloway. You can't talk about Mount max in the nineteen sixties without talking about

Eb Holloway. For eighteen years he ran the institution, and of all the adults who were directly responsible for what those children endured as a superintendent, Holloway was arguably the most to blame. He was staying in the Beith House and Mount Meigs, so he was treated like a king. You know, I had the Gills come down and do all of the housework and stuff like that. It was he was almost like the master of the plantation. There's one specific and chilling detail that stays with Johnny about

Holloway even now. You know he larned everybody else, and he always smiled. He'll be being you to death if he be smad. I keep thinking about the adults who are running the school back then, mister Glover, mister Reddy, Fannie Matthews, and especially Evie Holloway. Who were they and why did they treat these kids, these children who were in their care so violently. The truth is we don't know too much about what was going on internally at

Mount Meg's back then. We search state archives and people's personal documents. We sent in public records requests, but we haven't found or received any personnel records. But what we do know is that no one really seemed to be penalized for what was going on. The Department of Social Welfare and the Department of Pensions in Alabama, they did

these annual reports every year. They came to the school and they examined the grounds and they typed up these perfunctory reports that are based basically the same every year, and they just don't mention the violence that these kids were enduring and the couple of times that it is like alluded to. It's framed as fair punishment. It's framed as reasonable. And it wasn't just that Holloway faced no backlash. It was also that he was celebrated. He was praised

across the state. In fact, if you judged Holloway based on what was written about him in the newspapers, you would honestly think this guy was a hero, a champion for kids, finding tooth and nail to secure adequate resources and funding for them from the state of Alabama. And this is an important thing to keep in mind here too, because it wasn't just the abuse that was the problem. Some of Mount Mex's problems couldn't have been solved even if they had had the best staff in the world.

It was a chronically underfunded school. It won't be surprising to know that the white industrial schools in Alabama had far higher budgets while housing fewer kids and out Mount Megs. You know, there was this double standard. A judge in the nineteen fifties said that he did not want to approve more money for Mount Megs because they could just sell the crops they grew to fund themselves. At the white schools, no one was telling them to make their

own money off of crop yield. But at Mount Megs, the state just kind of expected the black people to make it work. Here's the other thing about Ebe Holloway. He was technically never qualified to run Mount Megs. He had no real background as an educator, had never worked at a school like this, So why did the state of Alabama hire him. Holloway was born in nineteen oh six in South Carolina. He moved to Alabama to attend the Tuskegee Institute founded by Booker T. Washington, an institution

that becomes an important part of our story. We'll get to that next episode. Holloway went into agriculture, not education, but he started gunning for the job at Mount Megs in nineteen forty four, before the previous superintendent, JR. Wingfield had even retired. Wingfield spent twenty seven years on the job and was a prominent black figure in the community,

considered part of the upper echelon of black society. Starting before Wingfield even retired, Holloway wrote letters to the governor asking for the job, and then the governor quickly received a flurry of other letters from Alabamians recommending Holloway for the position, including from white men, some of whom Holloway barely knew. It became clear that he was asking anyone he could to recommend him, despite not being qualified for

the role. But even with all those recommendations, Holloway didn't get the job. The governor appointed as superintendent another black man with more experience, named Amos Parker. Holloway instead was hired to oversee the agriculture at Mount Meg's, but Holloway didn't give up. He still wanted to be superintendent and seemed willing to sabotage Parker in order to get the job in nineteen fifty one. Five years later, the governor got another letter about Mount Megs, this time from a

white county judge. The judge asked that Amos Parker be replaced as superintendent because of the hotbed of Negro political activity in Montgomery. The judge insisted in his letter that Parker belonged to the radical element that is causing much trouble through agitation, unrest, and scheming. The judge recommended Holloway as Parker's replacement because, in the judge's own writing, Mount Megs is in great need of some white oversight, and Holloway seems to be a good Negro. He is educated

and doesn't dabble in political activities. The governor wrote back and said that the judge had bad information that Parker didn't have radical tendencies, and it was true that as far as we know, Parker wasn't particularly radical, but he was more willing to speak out about what Mount Meg's needed. In March of nineteen fifty one, he went to the state legislature and he told them that the conditions at

the school were deplorable. He said the kids were using fertilizer sacks, for towels, and that many of them didn't even have shoes. It's not radical to say that kids should have shoes to wear, but it was bold. It made the news, and eventually the governor decided that Parker was more trouble than he was worth. In nineteen fifty two, it became official. The governor fired Parker and made eb Holloway the new superintendent of Mount Meg's. Every superintendent up

until and including Holloway was black. In fact, Mount Megs was operated exclusively by black people for a long time. That was mandated by law. Black children were not allowed to be taught by white teachers, but even after the law changed, the pattern continued. Still, state officials were specific about what kind of black people they wanted in the job.

It seemed the State of Alabama preferred staff members who were ambivalent to the black quote unquote cause timpt Timpta ride, timpte, cities want to check lime light, oh bo, and little minds oh bo a little line. By the time Denny Abbott started working as a juvenile probation officer in nineteen sixty one, it was clear that Holloway's allegiance wasn't to the kids, but to the white board members. He would do whatever the white authorities are, those board of trustees

told him to do. They raised some pigs and other chickens and things like that at Mountain Mason. So when they slaughtered them for the meat, guess what happened. The white trustees pulled up in their brand new cars and all of the meat was put into the trunks of their cars and they left and the kids had nothing.

You had a battle and shake balls put a captain, And Denny says that despite Mountain Magsi's charter that saved three seats on the board for black people, all the trustees in the nineteen sixties were white, safe for one Holloway, and many of the board members had land surrounding Mountain Megs. So when it came time to get their crops harvested, guess who did the work. They would pick up the phone and call the superintendent, and the sup the kids

over there in their truck. Did they get any compensation for that? No, all I got was beatings when they didn't do enough work or the overseers didn't think they picked enough cotton, and they were physically beaten every day in the field. So I don't know how much more you could describe a slave camp than that tell them to read in chemn tay right the cheven two ties want to check line right before. In some ways nineteen sixties, Mount Megs was like an early prototype of the for

profit prison, but it certainly wasn't designed that way. When a black woman and student of Booker T. Washington named Cornelia Bowen founded Mount Megs in nineteen oh eight, she envisioned a safe haven for black kids who weren't being served by the state of Alabama. She believed in reform through industrial education, and often she was successful, and without her, America might not have had one of its most legendary black athletes, baseball player Satchel Page. That's next time, Unreformed.

Unreformed The Story of the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children is a production of School of Humans in iHeartMedia. This episode was written by me Josie Duffie, Rice and Taylor von Laslie. Script supervisors Florence Burrow Adams, and our producer is Gabbie Watts, who had additional writing and production support from Sherry Scott. Executive producers are Virginia Prescott, Elsie Crowley Brandon Barr, Matt Arnette and me. Sound design and mix is by Jesse Niswanger. Music is by Ben Soli.

Additional recordings are courtesy of the Alabama Center for Traditional Culture. The song's featured in this episode of From Vire Hall, Mary lou Bendoff with seb Petway and Richard Amerson. Special things to the Alabama Department of Archives and History, Michael Harriet, Floyd Hall, Kevin Nutt, Van Newkirk, and all of the

survivors of Mountmeg's willing to share their stories. If you are someone you know attendant Mount Megs and would like to be in contact, please email Mountmegs Podcast at gmail dot com. That's Mt m e i g S Podcast at gmail dot com. School of Humans