Due to the recent arrival of another Minnie McLean Smith. The next new episode will be with you next Friday, June thirteenth. In the meantime, we're heading back into the vault for this week's episode, going all the way back to the beginning of season two. England's Black Country, a region just west of Birmingham, is considered one of the

birthplaces of the British Industrial Revolution. It's centered around a thirty foot wide and unusually shallow coal seam, a product of once living trees compressed and buried for millions of years, returning to the surface like an irrepressible secret. There are some who say the trees can talk, and if they could, what secrets might they hold? In full for the first time, this is unexplained. Season two episode one Whispers in the Trees.

At nineteen hundred hours on Wednesday, January nineteenth, two thousand six, NASA's New Horizons Probe, propelled by the Majestic Atlasphe rocket, is launched into space, having begun its journey at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. The probe, which is part of the New Frontiers program, is the focal point

of NASA's first ever mission to Pluto. With the spacecraft being hurled towards its target at over thirty six thousand miles per hour, it will be another ten years before it begins to uncover the secrets lying in wait at the outer regions of our solar system back home, a week after the launch, in a small bedsit in London, a far more earthly discovery is about to be made. On the afternoon Wednesday, January twenty sixth a team of housing officials are making their way towards a flat in

wood Green, North London. The apartment is part of a complex known locally as Sky City, which forms an estate perched on top of a vast shopping mall. When the team arrive at the front door, noises from the TV can be heard emanating from inside the flat, an indication perhaps that the occupier is home. The office's subsequent knocks, however, go unanswered, and after a few minutes they decide to

break down the door. Stepping into the gloom of the flat beyond, the offices, are first struck by a cloying smell that hangs thickly in the air. Pushing the front door wider reveals a stack of unopened mail on the floor or the while the voices from the TV continue uninterrupted. A moment later, the officers step into the living room and make a gruesome discovery. Lying there on the sofa, illuminated by the incessant flickering of the TV screen, are

the skeletal remains of the tenant. A pile of Christmas presents lie unopened on the floor. The tenant was thirty eight year old Joyce Carol Vincent, and her body at Laine, undiscovered and unreported for over two years. Filmmaker Carol Morley was so moved by this revelation that she began an investigation to uncover who this tragically forgotten woman had been. Morley's beautiful and hypnotic film Dreams of a Life, released in twenty eleven, pieces together the story of Joyce's life

in an attempt to rescue her existence from obscurity. It is surely a fate that haunts us all the sadness of a life forgotten, an affirmation of a degree of meaninglessness too profound to comprehend. We see it in the propensity for social media to so often operate not as a tool with which to explore each other, but rather a means with which to validate ourselves, our way of saying not only that this is who we are, but

in the way of old school room graffiti. Perhaps it is more fundamentally a way of merely saying that we were here, that we exist. You're listening to Unexplained and I'm Richard MacLean Smith. The British Industrial Revolution was a time of extraordinary physical and philosophical upheaval, a time, as the inimitable Humphrey Jennings once observed, that was borne from a sudden synchronicity of vision and the means of production.

But its fuel was, of course the land, the raw materials that men and women ripped from the ground and smelt it in the factories Throughout the country. Colossal cauldrons of industry sprouted up around the places where such fuel was most in abundance. One such centre, perhaps the most intense of the mall, was the Black Country, a region in the west Midlands of England whose very name proudly

bears the scars of its past. As the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle once wrote of the place at the time, a dense cloud of pestilential smoke hangs over it forever, blackening even the grain that grows upon it, and at night the whole region burns like a volcano, spitting fire from a thousand tubes of brick. At the height of the Revolution, the region was a city of chimney stacks, of iron foundries and steel mills, but its blood was coal.

In fact, traditionalists consider the real Black Country to only include the region just west of Birmingham, where the thirty foot coal seam comes to the surface, a product of once living trees compressed and buried for millions of years, returning to the surface like an irrepressible secret. There are some who say the trees can talk, and if they could,

what secrets might they hold. On the edge of the Black Country, there is an area of forest just outside of Birmingham that today is struck through by the busy A four five six road, But in years gone by it was a far more wild and darkly place. It is thought by some to be imbued with the sort of magic, a place where witches may have gathered, and perhaps or perhaps it is merely a place that echoes with the footsteps of ancient people who once walked and

eventually settled on the land. Indeed, it is possible that settlers may have frequented the area as far back as Neolithic times. Certainly, the nearby Witchbury Ring Fort is evidence of a local community having existed here as far back as the second or first century b c. By nineteen forty three, although signs of the fort can still be found,

they have faded well into the land. Half the world is in the grip of war, and for anyone who has found themselves mercilessly drawn into the horrors abroad, home is a distant and aching memory. For those left behind, home is a familiar but forever changed landscape, with or without the bombs. For Birmingham and the immediate surrounds, those bombs would come thick and fast, being as it was the second most populous city in the UK and a

major center of industry. It is hard to imagine that in the midst of such turmoil, something hidden, a secret closer to home might somehow penetrate the sound of those bombs. But in April of nineteen forty three, it did. What happened exactly one evening, under the cover of darkness, while explosives reigned down only a few miles away, has never been fully accounted for. It is a mystery that remains

to this day unexplained. Barely ten miles to the west of Birmingham, in the shadow of the Clint Hills lies the village of Hagley. On a warm spring evening, in the magic hour, as dusk begins to fall, four young boys of roaming through the Hagley Woods. The date is Sunday, April eighteenth, and the youngsters are Robert Hart, Thomas Willits, Bob Farmer and Fred Payne. With rationing starting to bite, the boys, although they wouldn't tell you, are searching for food, birds,

eggs or rabbits. If they're lucky, as their father's fight in foreign fields to protect the green and pleasant lands of home. The boys might be forgiven for thinking such wide open country to be as much theirs as any other Englishman, but such is the way of things. The land has been privately owned by the Lyttleton family since fifteen fifty six, and the boys are trespassing. The area is known as Hagley Park, taking its name from Hagley Hall, which in nineteen forty three is home to Charles John

Lyttleton the tenth Viscount Cobbham. The boys are about to make their way back home when if something catches their eye. A tree unlike any of the others around. The trunk appears strangely squat, having at some point been heavily coppiced. As a result, a shocking mesh of spinly branches has grown out at the top of it, forming the perfect sanctuary for nesting animals. Fifteen year old Bob Farmer volunteers to take a closer look and swiftly scrambles up through

the branches. Having soon reached the top, he looks down into the gaping hollow of the tree. In the fading light, he can just make out the familiar dusty white hue of a bird's egg. Reaching down. He stretches his arm deep into the trunk, but the egg remains tantalizingly out of reach. With the aid of a stick, he manages to move it, but it's bigger than he expected and seems to be wedged inside. With great care, Bob manages to dislodge the egg. As it starts to move free,

something dawns on him. Not only would this be the largest egg he had ever seen, but that familiar dusty white hue is a little darker and more yellow than it had at first appeared. It looks more like bone. When finally he lifts it from the hollow, it is clear that it is not an egg at all. It is, in fact a skull, a human skull. Bob holds it aloft as the other boys look on with a mix of fear and wonder. A quick discussion ensues. Is it really what they think it is? How old is it?

Should they tell someone? Fred is keen to show it to his older brother Donald, But in the end they decide to keep it between them, better that than risk

punishment for poaching on private land. With night fast approaching, one of the boys notices some material protruding from the farmer, pushes it into the skull, and taking the stick, climbs back up the trunk and carefully lowers the mistaken treasure back into the hollow, and there it might possibly have remained if it wasn't for the fact that unsurprisingly, something

of the event had followed the boy's home. The youngest, Tommy Willits, was finding it particularly difficult to erase the ghoulish image from his mind, an image that had found its way into his dreams. The next morning, unable to ignore it any longer, Tommy told his parents, who in turn wasted little time in telling the police. The next day,

Sergeant Charles Lamborne is dispatched to investigate. En route to the forest, Lamborne calls in on Robert Hart, the oldest of the boys, to help lead him to the strange and tree. A short time later, having pointed out the location, the young heart watches on as Lamborne, along with Sergeants Richard Skerratt and Jack Wheeler, and Constable Jack Pound take

it in turns to peer into the cavernous trunk. The boys had indeed found a human skull, but what they didn't know was that the peculiar tree was also hiding the rest of the body. One of the men remarks that the tree is an old and rotted witch hazel, also known as which elm, a tree long associated with the underworld, the name which derives from the Old English word meaning pliant and durable. This feature of which elm wood is one of the reasons it was traditionally used

to build coffins. The policemen request a forensic team to come and inspect the body, but they are unable to attend until the following morning. As a result, a volunteer is sought to guard the skeleton through the night. The task falls to Squadron Leader William Douglas Osborne, a former Special Constable home on leave for a few days. That night, Monday, April the nineteenth, Osborne kept watch over the remains of the unknown, encased like a missive from the underworld itself

inside the natural coffin of the old witch Elm. The following morning, on Tuesday, April the twentieth, Douglas Osborne was relieved of his duty by Superintendent Sidney Knight, Deputy Inspector Thomas Williams, and Constable Jack Pound. Later that evening, at approximately six forty the police were joined by Professor James Webster, head of the newly established Home Office Forensic Science Laboratory

at nearby Birmingham University. Webster was a foreboding figure described by writer John Mervyn Pew in his book Execution as a large, balding Scot with a glass eye and a monocle to enhance the vision of the other. He would often arrive on the scene scruffly dressed in baggy trousers and an old brown Harris tweed jacket with his tie hanging loose half way around his neck. With the ladder safely secured by the tree, the imposing Webster clambered up

to take a look inside. It was clear immediately the great access would be needed. An axe was called for and handed over to Constable Pound as the other men stood back and watched, Pound swung the axe and cut into the bowl of the tree. One blow was followed by another until a clear break had been made large enough to pull the skeleton out. With great care, the men worked together to free the bones before laying them

out gently on the forest floor. On the ground, the skeleton appears at first to be fairly intact, but Webster is quick to notice a number of missing fragments. After a quick search of the immediate vicinity, Webster stumbles upon the slightly chewed tibia of the left leg. One small midnight blue shoe with a crep's sole is also pulled

from the splintered trunk. With the pieces now laid out from the size and frame, as well as the few bits of material that remained, Webster could see instantly that the boys had stumbled upon the skeleton of a young woman. Later that evening, the first of the bones are delivered to the West Midlands Forensic Science Laboratory to be formally assessed by Webster and his assistant, doctor John Lund. Over the course of the next few days. The various sections

are deftly laid out by the two pathologists. Any external fabric is delicate removed, and slowly a body begins to take shape. Professor Webster proceeds while doctor Lund records its findings. He begins at the skull, noting that it is undoubtedly that of a female and there are no obvious marks of a fatal injury. On the side of the skull,

it's a small clump of mousey brown hair. An examination of the jaw reveals a clean and healthy set of teeth, with one peculiarity, a noticeable irregularity of the front two in sizes which overlap slightly. A piece of material, part of a khaki or mustard coloured dress that the deceased would have worn, is found lodged into the cavity of the mouth, suggesting a possible cause of death, perhaps placed

in the victim's mouth to hasten asphyxiation. Moving down the skeleton, Professor Webster notes no signs of disease or ill health, with the fine condition of both the h hyoid bone and the sternum suggesting that the victim was a woman below the age of forty. The pelvis reaffirms the victim as being indisputably female, with a particular feature in two of the hip bones suggesting a childbirth at some point, though this is deemed inconclusive. All in all, Webster finds

little unusual, with the major exception of one thing. The entirety of her right hand was missing. Professor Webster concludes the victim to have been a female of approximately thirty five years of age, of lower than average height, placing her at roughly five feet tall. The time of death is given as approximately eighteen months previously, due to the state of decomposition and the age of the tree roots which had weaved their way through what remained of the clothes.

Since the victim had to have been placed in the hollow before riga mortis, if, as Webster suspected, she had been murdered, it is likely that she would have been placed in the tree while she was still warm, possibly even alive. As such, she would likely have been murdered nearby, or at least driven to the spot in a significant hurry. An assessment of the rotted fragments of clothing reveal the remains of a mustard colored cloth skirt, as well as

a dark blue and yellow striped knitted cardigan. An inexpensive wedding ring is also found, which may have been worn for as long as four years. Back in the forest, members of the Home Guard, with the assistance of a local scout group, continue to comb the area. A second shoe is found not far from the tree, as well as a green glass bottle. A short time later, one

of the volunteers notices something protruding from the soil. As he digs into the earth, coils in horror as there, buried just below the surface is the missing right hand.

Taking Webster's bone and material analysis, the Worcestershire Constabulary put together a poster campaign in the hope of encouraging any witnesses to come forward, but as the days turn to weeks and then to months, despite evidence that the victim had possibly been married at the time of death and may also have borne a child, remarkably nobody comes forward.

Then an identity card is found in the woods, but when the police visit the owner's address, they are somewhat disappointed to find her alive and well, if a little bemused as to how her ID card was found so close to a possible murder scene. All in awe, the police trawl through over three thousand open reports of missing women but are unable to find a significant match. The irregularity of the teeth offered a glimmer of hope, but a subsequent check of all UK dental records again yields nothing.

The green glass bottle is also analyzed but reveals little of interest, but the police enjoys some luck when the crep sold shoes are traced to one specific manufacturer by the name of Silsby's, located in nearby Northampton. Almost six thousand pairs of the shoes have been made, but remarkably all of the owners are traced, except for those of six pairs that are eventually tracked to a market store

in nearby Dudley, where the trail goes cold. A similar process is attempted with the clothes, but curiously, all of the labels have been cut or removed entirely. A strange state of affairs, perhaps, but also one that was in keeping with the notion that the shoes might have been market bought, since store owners would often remove the labels

of the clothes they sold. In spite of the distraction and devastation of war, the mystery of the skeleton found in Hagley Wood, now being referred to in the press as the tree murder riddle, had continued to hold a firm grip on the local community, But as the months wore on, the tale of yet one more wartime death had begun to fizzle from the public consciousness. After six months, the police had drawn a complete blank, with no leads and not even as much as a name for the

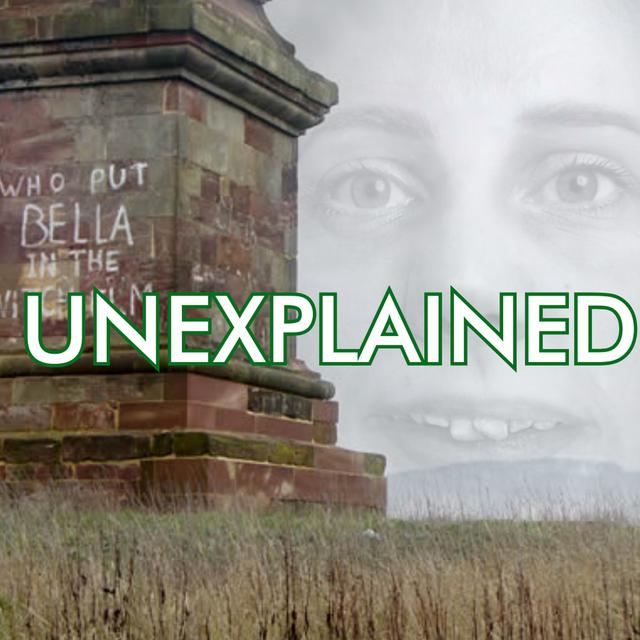

tragic forgotten victim. But all that was about to change. It was on one morning, some time towards Christmas of nineteen forty three, that the rising sun revealed a cryptic message hastily scrawled across a wall in the nearby village of Old Hill in chalk in three inch high capital letters were the words who put Lubella down the witch elm. Not long after, another message appeared scrawled on a wall

in Birmingham, declaring hagley Wood bella Again and again. The messages continued to appear, evolving each time, until eventually settling on what has perhaps become the most well known phrase, who put Bella in the witch elm? But who had authored these teasing questions? Do they really know who the dead woman was or what may have happened to her? And why are they not talking to the police? As if from nowhere, it would seem the authorities now had a name to work with, but the mystery was only

just beginning. As Christmas approached, at last, the authorities had something to work with, a name, or at least the derivation of a name. Now, the police began to focus their efforts on women with versions of the name Bella who may have gone missing. Around the autumn of nineteen forty one. One woman was of particular interest, whose name, Bella Lua, bore a striking similarity to the name Leua Bella, as depicted in the earliest of the graffiti linked to

the case. Bella. Leua's friends had become concerned when they lost all contact with her after she moved to Birmingham from Stamford Hill in London. Although Lewa's whereabouts were never officially established, she was eventually deemed irrelevant to the case. As for all the other missing bellas that the police looked into, they were found alive and well before long. The investigation it wall in defense of the Worcestershire Constabulary.

Nineteen forty one was a difficult time to be keeping track of British citizens, and with resources stretched to the limit, it is much to the credit of the force that such an extensive investigation was conducted at all. As the months passed and war eventually came to an end, the public interest in the case soon diminished by the summer of nineteen forty five, with the nation celebrating an end

to hostilities while mourning their countless other dead. The Tree murder riddle was fated to remain unsolved and forgotten, but someone was about to make a startling claim concerning a vital piece of the evidence that they believed had been criminally overlooked, the severed right hand back In eighteen ninety eight, at the age of thirty five, doctor Margaret Murray was making a name for herself in the field of egyptology.

She had just become the first female lecturer in archaeology in the United Kingdom, having accepted a post at University College London. She would continue to work and teach at the university until her retirement in nineteen thirty five at the age of seventy two. Although formerly an anthropologist and historian, Murray was perhaps best known for her highly controversial views regarding the history of witches. Her primary theory became known

as the witch cult hypothesis. The theory suggests that, rather than being the hapless victims of vile and arbitrary witch hunts, witches persecuted throughout European history, where in fact followers of a definite religion, with beliefs, rituals, and organization as highly developed as that of any cult. What drew her attention to the Hagleywood case was the curious revelation that the right hand had been found separated from the rest of

the skeleton and buried in the ground. The police merely assumed it to be the work of an industrious forest animal. To doctor Murray, however, it suggested something far more sinister. She believed that, instead of being a gruesome but incidental off cut, the hand had in fact been removed and placed in the ground deliberately as part of an elaborate occult ritual. Doctor Murray suggested that the severed hand may have been used to create a magic artifact known as

a hand of glory. Traditionally, such totems were made by removing the right hand of a convicted criminal, followed by the casting of a spell to invest the separated extremity with magical power. A bizarre suggestion, you might think, but not so, she believed if the victim had been considered to be a witch. The theory was given more weight by the location of the body, As outlined in James George

Fraser's groundbreaking book The Golden Bough. There is a rich tradition in Celtic and Pagan beliefs of investing trees with spirits and sometimes souls of their own. In addition, there are some who believe that certain trees have the power to bind magic. There are some who believe Hagley Wood to have long been a traditional meeting place for covens of witches, and it certainly wouldn't have been the first time that an occult ritual had been conducted in England.

During the Second World War. In August nineteen forty, Gerald Gardner, a well known follower of pagan witchcraft, along with the number of other members of the New Forest coven performed a magic ritual that became known as Operation Cone of Power. It was hoped that the operation with Oltimate dissuade the High Command of Nazi Germany from invading the United Kingdom. It is also important to note that doctor Murray's theory wasn't based on any personal belief in the magic of witchcraft,

but rather the notion that such practices did occur. Whether or not a hand of glory had any discernible power, it remains that somebody willing to believe in such things may have enacted some form of ritual in the murder

of the unknown woman. In any case, despite influencing a number of well known authors such as Aldus Huxley and Robert Graves, Murray's Hagleywood theory and her witch cult hypothesis have been roundly discredited, and in reality, there is little to support her claim that the victim had been subject to a ritualistic killing. What Murray's theory did do, however, was to enact a sort of magic of its own.

Such spells tend to be most post during times of uncertainty, when a scapegoat is required to make sense of the ills of the world. Perhaps it was only ever going to be a matter of time, but soon a bogey man would be brought forth from the fog of truth. With all the talk of ritual murder and black magic, fueled by a press ever ready to fan the flames of a salacious story, many became convinced that local travelers were to blame. The rumour would persist for ten years,

but all that was about to change. In nineteen fifty three, a journalist at the Wolverhampton Express and Star, writing under the name Questa, decided to reassess the evidence. His real name was Wilfrid Bifford Jones. Bifford Jones, who had never been convinced by the reductive traveler theory, revisited the case in a series of articles appearing in late November of

nineteen fifty three. Concluding the series, in a third and final article published on Friday, November twentieth, Bifford Jones notes, whether the young woman is supposed to have been a gipsy who was ritualistically murdered with witchcraft or after a trial by her tribe, well, I do not accept it. It is true that there had been gypsies for years in the area, but every crime is laid at the

door of Romany's. For Bifford Jones, the suggestions of witchcraft had been a gross and fanciful obscuring of the facts. It was a gallant and single minded campaign that fought to wrestle the case back from acceptable fiction to more unsettling fact. But nobody could have anticipated what came next when a few days later a Strange's letter landed on Bifford Jones's desk. It was postmarked Claverly, Wolverhampton and dated eighteenth of November nineteen fifty three. It read, my dear quest,

finish your articles regarding the witch Elm crime. By all means, they are interesting to your readers, but you will never solve the mystery. The one person who could give the answer is now beyond the jurisdiction of earthly courts. The affair is closed and evolves no witches, black magic or moonlight rites. Much as I hate having to use a nom de plume, I think you would appreciate it if

you knew me. The only clues I can give you are that the person responsible for the crime died insane in nineteen forty two, and the victim was Dutch and arrived in England illegally about nineteen forty one. I have no wish to recall any more, yours, sincerely, Anna. It is not uncommon for people to claim knowledge of crimes they have no connection to, but something of Anna's letter rang true to Bifford Jones. After a series of pleas for Anna to come forward and reveal herself, a few

days later, against all expectation, she did. And so it was on one cold morning at the local police station that Anna proceeded to reveal everything that she knew. Her name was Una Hainsworth, and this was her story. Sometime in the early thirties, Una had met and fallen in love with a dashing young man called Jack moss Up. Not long after, the young lovers would be married and expecting their first child. Sure enough, in nineteen thirty two, with the couple still in their teens, a son, Julian,

was born. As the country slowly clawed its way back from a decade of economic stagnation. Here encapsulated in the face of their new born baby was a renewed sense of hope for the future. But that hope would be short lived, for there as a shadow looming over the young family, a shadow that was soon to fall across most of the world. On Sunday, September third, nineteen thirty nine, at eleven fifteen, a m families up and down the land huddled around the wireless as Nevill Chamberlain announced that

the country was at war. Less than a year later, on Friday, August ninth, nineteen forty, the first of many bombs dropped on the Midlands. What followed was just under two years of sustained bombing of the heavily industrialized region. For Jack, perhaps to his relief and shame, as a skilled factory worker, he was exempt from the draft and

was instead assigned to work in coventry building munitions. But as the months wore on, UNA's relief that Jack had avoided the draft was tempered somewhat by a sudden change in his character. He started to drink more and stay out later, often at a new favorite haunt, a lively place on the edge of the Clent Hills called the Littleton Arms. He started buying new clothes, including an RAF officer's jacket to which he was not entitled. He had

also started to accrue money from an unknown source. Una was particularly suspicious of the new crowd he seemed to be hanging out with, a suspicion that was further aroused when one of the crowd turned up one night at their home. The enigmatic man, who gave his name as Van Rolt, was well dressed and claimed to be from Holland, with a seat seemingly endless disposable income, despite no discernible

occupation to speak of. One evening in the spring of nineteen forty one, after yet another late night, Jack returned home drunk and agitated. He'd been at the Littleton Arms again with Van Rolt, where they were joined by what he described as the Dutch piece. Jack claimed that the woman had become awkward and later passed out, at which point Van Rolt decided to play a trick on her. After carrying the woman to Van Ralt's car, the pair drove to a nearby wood and dropped her unconscious body

into the hollow of a tree. They had only meant it as a joke, he said, believing in the morning that she would come to her senses. In the weeks that followed, it was clear to Una that something was playing on Jack's mind. As he retreated further into himself, and his behaviour became increasingly erratic. Una eventually had enough, so she left, taking their son with her. For Jack, now without his wife and child to keep him company,

things began to unravel drastically. It wasn't their leaving that tortured him every night, but rather what had crept in in their absence. Later, after Una and Jack had divorced, Jack confided in Una. He told her that he was being driven mad by the recurring image of a woman's face leering at him from inside a tree. But it wasn't until Una heard that a skeleton had been found in Hagley Wood that she put the two events together.

Back in the police station or those years later, the interviewing officers are dumbfounded by UNA's statement and immediately demand a contact address for her ex husband, but she couldn't give them one. Jack had been committed to a psychiatric hospital in Stafford in nineteen forty two. A few months later, at the age of twenty nine, he was dead, apparently driven insane by his recurring nightmare. But what really shook

things up was UNA's parting thought on the matter. Van Rolt, she believed was the spy there is no firm evidence to suggest that Jack Mossup had found himself embroiled in a spy ring. So what to make of UNA's story. Certainly, much of it is true. She did indeed have an ex husband called Jack Mossup, who had been a regular visitor to the Littleton Arms. It is also true that he would later die in a psychiatric hospital in nineteen

forty two. Police also had some luck in tracing the mysterious Van Rohlt figure, but nothing untoward could be found. It could be said that much of UNA's story begins to make more sense if her spy theory is applied. Certainly, in his capacity as a munition's worker in Birmingham, Jack would have been uniquely placed to pass off useful information to the German Air Force. Although UNA's spy theory was never officially confirmed, it was a theme keenly picked up

fifteen years later by writer Donald McCormick. In nineteen sixty eight, McCormick is alleged to have conducted a series of interviews with a former Nazi called Franz Rathgeb. It turned out that a number of spies had been active around the Midlands after all, at precisely the time that the unknown woman would have gone missing. One of those spies was Rathgeb.

Although he claimed not to know anything of the murdered woman, he did recall a fellow spy by the name of Leara who had a Dutch girlfriend called Drunkers Clara Bella Drunkers, who was herself a spy living in the Birmingham region. Intriguingly, she would have been around thirty years old at the time of the murder and had a regular front teeth

similar to those noted on the skeleton. Could it be that the fruitless search of dental records all those years ago hadn't failed because of an administrative error, but merely because the woman had not actually been from the UK. McCormack further alleged that he later came across some interesting information in declassified papers from German military intelligence. The papers suggested that a spy had been parachuted into the Midlands in nineteen forty one, but had then failed to make

contact with their handlers. The name listed for the spy was Clara Bella. Needless to say, this theory two remains unconfirmed. However, on the eighteenth of May nineteen forty two, the British Navy intercepted an unregistered boat just off the coast of the UK. In it were three Dutch nationals who were promptly interrogated. After routine questioning, two of the men were deemed rational and of little threat. The third, on the other hand, became hysterical at the first sight of the

British officers. He was immediately arrested and later convicted under the nineteen forty Treachery Act on suspicion of being a spy. His name was Johannes Marinus Drunkers. Was this the man Franz rathgeb knew as lera come in search of his missing wife? Sadly we will never know. On New Year's Eve of nineteen forty two, Johann's Drunkers was executed in Wandsworth Prison in London. Towards the end of the twentieth century, a number of British wartime files were declassified, with one

proving of particular interest to our case. On the evening of January thirty one, nineteen forty one, just above the town of Ramsey in Cambridgeshire, high up in the night sky, a man was silently drifting down to earth. No one saw the black spot as it fell hard and fast, landing with a bump in a field next to Dove House Farm. Two men, Charles Bulldock and Harry Caulson, had been walking by the area shortly after when they heard the sound of a revolver being fired into the air.

Locating the source of the gunshots, Bulldock and Coulson were astonished to find a man lying on his back in a field surrounded by the silken canopy of a parachute. The man, who was in some distress, had clearly broken his leg. Coulson ran immediately to fetch James Godfrey, a member of the Home Guard, who in turn telephoned Ramsey Police Station before accompanying Coulson to take a look at the prostrate man. Godfrey later noted that the man had

been wearing civilian clothes underneath his flying suit. They also found in his possession an attache case four to five hundred pounds in one pound notes and a wallet. Together, the three men bound the parachutist's leg and waited for further instructions. A short time later, Captain William Henry Newton arrived on the scene, and began to question the mystery man. He gave his name as Joseph Jacobs and claimed to have flown over solo from Luxembourg before bailing out of

his plane. Jacobs was then loaded onto a horse and car and delivered to Ramsey Police station. Once detained, Jacobs was asked to open the attache case. Inside they found a wireless set, as well as a pair of headphones and batteries. They also found a map, on which was

marked the location of two RF satellite stations nearby. But Jacobs is also carrying something else, something found tucked away deep inside his pocket a picture photograph of a glamorous looking woman, on the back of which was a message written in English. It read my dear, I Love you forever, Your Clara Landau, July nineteen forty. The woman is Clara Sophie Bowler born in Ulm, Germany, on the twenty ninth of June nineteen o six. In nineteen forty one, she

would have been thirty five years old. She is a cabaret singer and sometime actress who not only worked for a number of years performing in music halls across the West Midlands, but speaks fluent English with a Birmingham accent and was known locally as Clara Bella. Not only that, but according to Jacobs, she is extremely well connected to the Nazi Party and had been recruited as a spy with plans to drop her into the Midlands region. Finally, it seemed that the pieces were coming together. Is it

possible that Clara Bowler is our unknown woman? Not so, according to Jacob's granddaughter Gizelle, whose own website on the subject provides an exhaustive account of the life of Joseph Jacobs. As Giselle's research details, the skeleton found in the witch Elm Tree suggested a woman of around five foot in height. Clara Bowler, as has been well documented, was substantially taller

at almost six feet in height. In a final blow to the theory, it was also discovered that Clara had in fact died in Berlin on the sixteenth of December nineteen forty two. Joseph Jacobs was eventually tried and convicted of being a spy and sentenced to death by firing squad. Jacobs protested his innocence to the end, declaring that he was a friend of England and had arrived to help in her fight against the Nazis, but it was to

no avail. On the thirteenth of August nineteen forty one, Joseph Jacobs became the last man ever to be executed at the Tower of London. Thinking about the mystery in its entirety, it is quite striking when you consider that perhaps the least strange element of the whole thing is that a woman had been murdered, and most likely by a man, And not only had she been disposed of with such apparent ease, but there seemed nobody willing to

come forward on her behalf. According to writer and broadcaster Steve Punt, who investigated the witch l murder as part of his Punt PI series broadcast by the BBC, there was one report at the bottom of a police file that is so often overshadowed by the louder, more colorful components of this compelling mystery. It notes a missing persons report logged some time around October of nineteen forty one, a sex worker by the name of Bella had gone missing.

Could it be that that same Bella, a woman whose initial disappearance had perhaps been deemed unworthy of investigation, was the woman they had been searching for all along. There was one other report recorded shortly after the skeleton had been discovered, an eyewitness account by two Home guards who had been wrapping up their nightly patrol near Hagley Wood one evening in the autumn of nineteen forty one, when the sound of an approaching engine stop them in their tracks.

As the guards looked down to a turn at the bottom of the road, a scattering of light is followed shortly by a vehicle appearing from around the bend, before swiftly pulling in to the side of the road. The guards approach with caution, surprised to see a private vehicle driving round these parts at this time of night. As they neared the vehicle, one of the guards holds a light up to the driver's window and knocks on the glass. The driver blinks into the light and rolls down his window.

He smiles awkwardly as he hands over his ID. The guards are surprised to discover, judging by the jacket he is wearing, that the man is an RAF officer. Shining a light into the vehicle, the patrolman noticed there is someone else in the car, huddled under an overcoat, lying very still in the passenger seat. At the look on the faces of the guards, the officer gives an embarrassed shrug. The guards return the ID, which is gratefully received by the driver, who proceeds to roll up the window before

driving away back into the night. Unexplained as an Avy Club Productions podcast created by Richard McClain Smith. All other elements of the podcast, including the music, were also produced by me Richard McClain smith. Unexplained. The book and audiobook is now available to buy worldwide. You can purchase from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Waterstones, and other bookstores. Please subscribe to and rate the show wherever you get your podcasts, and feel free to get in touch with any thoughts or

ideas regarding the stories you've heard on the show. Perhaps you have an explanation of your own you'd like to share. You can find out more at Unexplained podcast dot com and reach us online through Twitter at Unexplained Pod and Facebook at Facebook dot com. Forward Slash Unexplained Podcast