This episode is brought to you by Juneteenth LP, a dynamic ensemble and organization dedicated to celebrating Black history and artistry through music. Learn more about their powerful mission and upcoming events at juneteenthlp .org. Thank you Juneteenth LP for supporting this episode. Welcome back to the piano part, everyone. And thank you so much for joining me today for this

very, very special episode. Today marks the season five finale, and I truly cannot think of a more powerful way to close this remarkable chapter of authenticity and joy than with the conversation you're about to hear. This entire year has been a deeply meaningful one. 20 episodes featuring 21 phenomenal guests from six countries across

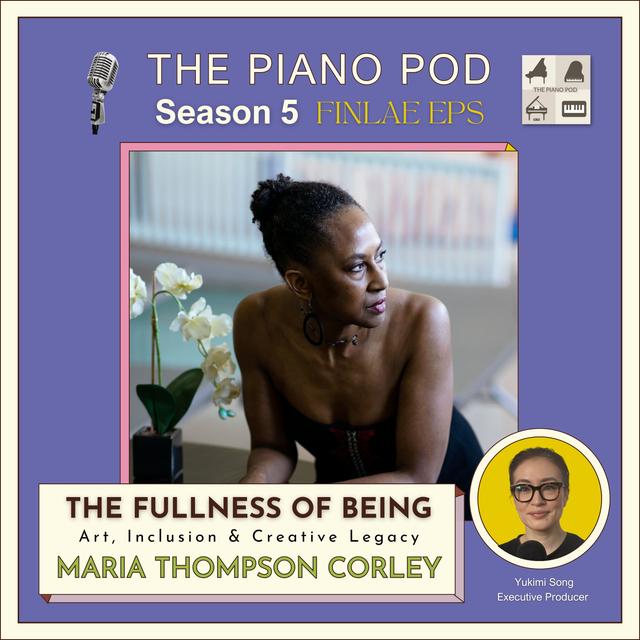

three continents. We have grown into a global community with over 2 ,900 YouTube subscribers, an increase of 300 from last season, and a significant rise in our podcast downloads across all audio platforms. We opened the season with the legendary Sarah Davis Buchner, and now we conclude with the extraordinary Maria Thompson Corley. What a journey it has been. And this year has brought even more milestones. We launched our new substack with over 10 % of subscribers now supporting

us as VIPs. We were named one of three finalists for the 2025 Quill Podcast Awards in the Best Video Podcast category. None of this would have been possible without you, our listeners, supporters, and collaborators. I am so incredibly grateful to each one of you for being part of this journey.

Amid a year of challenges in the arts world, including widespread cuts to public funding, this season reminded me that especially in uncertainty, we can still find beauty, connection, and a deep sense of purpose in the work we do as artists. Now today, to commemorate Juneteenth, we are continuing our partnership with Juneteenth LP, and I am honored to welcome today's guest, Dr. Maria Thompson -Corley, a powerhouse of creativity and compassion, whose artistry defies categories.

Maria is a concert pianist, composer, poet, novelist, educator, voice actor, and advocate for inclusion in the arts. But it's her honesty, clarity of purpose, and depth of care that leave the most

lasting impression. In this episode, we talk about her bold reflections on inclusion and cultural ownership in classical music, her discography and original compositions ranging from solo piano to opera, how real life experiences, the joys and the challenges of raising a family have shared her artistry and redefined her understanding of success. and her far -reaching vision of inclusion, not as a token representation, but as a meaningful cultural shift rooted in authenticity, creativity,

and care. This conversation is everything I hoped Season 5 would be. Brave, generous, and deeply human. Although this is our final episode of the season, I can't wait to return in September for Season 6 with the themes of creativity, and connection. We already have an exciting guest lineup in the works and an incredible live event on October 4 at the new school's Stiefel Hall hosted in collaboration with Manus Prep. So please

stay tuned for more. Until then, thank you for listening, thank you for supporting, and please enjoy this unforgettable Season 5 finale with the incomparable Dr. Maria Thompson -Corley. You are listening to The Pianopod, where we talk to the brightest minds in the industry about how they are bringing the piano into the future and thriving in a complex, ever -evolving world. Welcome to The Pianopod, Maria. It's truly a joy and honor to have you with us today. Well,

I'm so grateful you asked me. Of course. Yes, I've actually your name was on the list guest list wish list for since season one. Wow. Yes, and I just didn't get a chance to invite you. So I'm so grateful. And then anyway, and your multifaceted career as a pianist, composer, poet, writer, I didn't realize this part of your life, like being a writer and poet, I never knew of that. And so I'm very excited and an educator

and of course, an advocate husband. really nothing short of inspiring and I'm in awe of your artistry and also presence today and then you are redefining what it means to be a classical musician of the 21st century not only through your exceptional creative output but through the depth, integrity and heart you really put into everything you do. Five years ago which is 2020. So that's when I attended your workshop, online workshop that was hosted by the Piano Teachers Congress of

New York. Yes. And then you did the presentation titled Widening the Main Street. And you introduced us to so many wonderful Black composers, including your piece that you featured towards the end. You performed your piece. But so you opened up the workshop with a powerful reflection of, you know, with so much music already in the mainstream,

why widen it? And the answer you said was very obvious, like, and you called it out that the long standing assumption around the what defines complexity, who gets to be seen as talented, who gets to hold cultural ownership over the classical canon, biases that still impact programming, pedagogy, school leadership, representation in higher positions throughout the classical music, and so on until today. So in five years, how do you think we are doing in the classical industry?

I mean, I've seen some changes, definitely. For example, I've been asked by the Royal Conservatory of Canada to submit pieces for inclusion in the repertoire, and a couple of my pieces were accepted there. I was also recently contacted by the... I'm thinking of the... I'm blanking on the acronym or the letters that, but it was the Royal Conservatory equivalent in London, England. And so I submitted a little piano piece for their fifth grade collection.

Is it ABRSM? That's it. Yes. I didn't want to get them wrong. I should have been thinking of what they, yes. Board of the Royal Schools of Music, yes. So yes, I was asked to submit a piece, so that's good. And I think, I know that they said that there were nine people they approached. I don't know who the other ones were, but I see the effort at least continuing. And I don't know, you know, how long it will continue, but I think that it will be harder to put the genie back

in the bottle, honestly, at this point. even those who would like to put the genie back in the bottle, I think it's a little bit too late for that. And people are realizing that, yes, there are a wide range of people, whether they were women or whatever their ethnic background or racial background or whatever, however else you want to define it, who have created music that is worthy of hearing and worthy of performing and studying. And yeah, I feel like now I saw

something the other day. This is about women specifically. And I don't know what the list of major orchestras, you know, how they determined that, but I'm sure, you know, their criteria were very stringent. That performed music by women was still seven percent or something like that. So, you know, obviously there's work to still be done, but I feel hopeful. that this direction will continue in the artistic community and that there's not a big drive to turn back

the clock in that regard. Doesn't seem there is really. Yeah, I think we've come a long way since then. Although, you know, the progress sometimes we feel so slow. But, you know, in retrospect, wow. You know, I think our mindset has shifted tremendously. I think it was like hearing the if, for example, black pieces by black composers was so rare, or should I, you know, the mindset was like, should I include? Can I play this? But that's not the case anymore.

Yeah. And what I what I find is that, and understandably, way past her death, Florence Price had a huge renaissance. And I feel like on one hand her music is amazing on the other hand it sort of checks two boxes at once and people don't always explore you know some further corners so to speak you know it's sort of like you're doing Florence Price and I saw that at least to begin with with some of the programming of concerts and orchestras and things like that so I'm I'm not against that

at all. But, you know, I'm hoping that they'll continue to look at other people. And I think that they are. I think I'm on the artistic committee of a music festival that's local. It's Mount Gretna. And so that's, you know, not too far from here. And I noticed that most of the programming of the classical performers includes, you know, it's not just the straight canon anymore. You know, there's always something that isn't. part of that. So it's good. Oh, wonderful. Yeah, it's

so great to hear. But I know that you've been performing, excuse me, compositions by black composers for even before way before 2020. I know that I in fact, the albums, I think first one was produced in 2005. The soul scape or 2006 something 2006 was the release date for soul scapes. I actually did several years before that. a recording of pieces by Leslie Adams. Yes, that

was my first solo piano recording. And I will say that when I was coming through school, I grew up in Western Canada, and obviously there was no focus on music by Black composers there. there was some focus on female composers in that, you know, Violet Archer was very well known there, Jean Coulthard. So they were well respected. And in fact, Violet Archer taught at University of Alberta where I got my undergraduate. But it was something that, you know, it just wasn't

even in my mindset. And it really could have been, I guess, I just I don't know if it was a lack of representation that I didn't really see. Black classical composers and so I didn't really think there were any and I give credit to the people who Challenged that obvious fallacy.

I mean, why wouldn't there be any but you know, certainly not in Canada And I was focused on learning some of the great standard literature pieces that I'd heard and wanted to play and all that So when I got to Juilliard Again, it wasn't a focus and my teacher was wonderful, you know on George Shondor was, you know, that wasn't a focus of his either. Now, the Schoenberg was right up the street. I could have gone and done some research and I certainly played spirituals.

And I started to become acquainted with a little bit of art song. And I was a pianist for Opera Ebony, which was based in New York. And so they would do scenes from, for example, Dorothy Redmore wrote a piece about Frederick Douglass and I performed different scenes from things as part

of concerts with opera ebony. But again, for whatever reason, I didn't draw the line or I wasn't curious enough or whatever it was in my youthful ignorance that I just kind of wanted to learn what I wanted to learn and had always wanted to learn. And it wasn't until I went to Florida A &M as a professor. that I was exposed to, first of all, Margaret Bonds and Troubled Water, which is, you know, one of her most famous pieces, and some pieces by Samuel Coleridge Taylor.

And, you know, then that sort of cracked the door open, and that was also the period that I met Daryl Taylor, who is the founder of the African American Art Song Alliance. And he introduced me to Leslie's music. He was a real champion of Leslie's music to begin with and then sort of championing all kinds of black composers. And through him, I met Leslie. And it was a performance that Daryl and I did that led Leslie to give me these new piano etudes that he was working

on. He had decided he was going to write 26. For whatever reason, that number just appealed to him. And so he asked if I'd be interested in getting them. And of course I was. So having been given these pieces that hadn't been performed, I was able to world premiere. Five of them had been performed. I world premiered the first 12. And also through Daryl, I had met Louise Taupin, who is, at the time she was running Vidaemus

records. I mean, she stepped away from that now, but asked if she'd be interested in a recording of Leslie's, these 12 etudes. And that's how that came about. People I knew introduced me and gave me opportunities and I was able to capitalize

on them, I guess. this when you mentioned about you realized that you didn't know much about black composers that history of you know black composers and so on then you started more incorporating I think that's what what's all about right like a mindset a shift of mindset that happens so we are taught oh play you know the usual composers like Bach, Chopin, they are all great. And that's what the conservatories, you know, traditionally expect of you to perform all these wonderful

greats in perfection. But then there are so many other composers that we missed out and we are not even taught or educated. And also we feel like, oh, we have to do all these, you know, mainstream greats in order for us to be considered or even in order for us to feel classical musicians. Does this make sense? Yeah, no, I understand

what you mean. It's like if you're not covering that core, then, you know, are you really, you know, so I suppose you can play whatever and it can be extremely difficult or expressive or whatever else. But, you know, someone sitting somewhere is like, yes, but could they play Brahms or whatever, you know? Now, I think it again, it's important to cover those composers. And I don't think that we were trying to get rid

of them. It's just I mean, there are pieces that have been played a gazillion times for good reason. There's a reason why they're so famous. And I think that it's more of a challenge of expression and exploration if you have a piece of music that doesn't have like 200 YouTube videos from which, especially as a student or even as a professional pianist, that you have to create You really have

to decide what you want to bring with it. You are in conversation with the score, and you are not relying on, okay, well, I like how Horowitz did this, and I like how Rubinstein did this, or whoever else. Yeah, so I think it demands more of you as a musician to approach something that doesn't have this long track record, really. You mentioned that about your recording of Leslie Adams etude. really enjoy them so much. What

an incredible series of etudes. And we're going to circle back, but before, I kind of want to know your artistry today. So I usually start up a conversation with, you know, if you were to capture the essence of your artistry, mission and passion in just a few sentences, how would you define who you are as an artist today? Well, I believe that everything that I do, the through

line is storytelling. So whether I'm using words or whether I'm using music, whether I'm creating the music or interpreting the music, I believe

that we should be taking on a journey. And there should be that sense of, you know, I mean, even abstract storytelling, even if I don't have a specific program in mind that I've created for myself, we should Be experiencing a mood or a series of moods or something that is going to speak to us The listener and obviously it has to speak to me before I can try to translate that to the listener so Yeah, I think that that is definitely the through line is just I want

to express ideas or tell a story in some way Wow, yeah, I mean make sense because you have such a gift of storytelling and writing and which we're going to explore a little bit more later. But now also, we briefly spoke on the phone a few weeks ago and to prepare for this conversation. And you share the motherhood is as important and a central part of who you are, not just as being a mom, but also being a person and as an artist. And you wanted to bring that into our

discussion today. So how has being a mother of two artistic children, because I think your daughter is a wonderful singer and then your son, who is also the neo -divergent spectrum on the spectrum. And also he has a wonderful, he's a wonderful painter. Yeah. Oh, my goodness. So talented. Thank you. Yeah. I mean, I don't know why I'm saying thank you because I didn't do anything.

But yeah, I have found. Now, I will say that I wasn't somebody who, you know, grew up as a little girl saying, oh, I can't wait until I can be a mom. I'm just, you know, I was really more focused on being a pianist. And I believed that and I know everybody has to make a definite choice. If you have children, some people choose to like walk away from whatever their career

was. I felt like having had this passion for being a musician since I was very young that I didn't want to like amputate part of myself, which is what it would have felt like, you know, when I had children. However, I felt like it was a huge responsibility if you decide that you're going to bring people into the world that they didn't ask for that in my estimation. So, you know, you have to take that very seriously.

So. I've tried to find a balance between doing the things that I really feel are core to me or have helped me maintain even some semblance of sanity and empowering and encouraging my children. And because my son is on the autism spectrum,

I'm kind of grateful. Well, I'm very grateful that I have been able to do something that allows me to work from home so much, because so much of what I do is practicing, I teach in my house, I compose in my house, and it's not like I never leave my house, but I have more flexibility because of that. And he is a very social person. So it's good that, you know, he has opportunities to

go out and be out without me. So I'm grateful that he was born in a time that and in Pennsylvania, the services for people on the spectrum are actually rather good. And so, yeah, so so I feel grateful for for where we are right now and the timing in that people were doing more. for people on the autism spectrum. But it certainly informs everything I do. So I'm not, I don't know if I would have enjoyed when I was younger traveling all the time if I had had that opportunity. In

the end, it wasn't something that happened. Although I have a couple of trips, I've had more trips lately, which is shocking to me. But, you know, I did some of that. But, you know, once he was born, I certainly wouldn't have been, you know, okay, can you go here or there for a week? And it was not, yeah, it was sort of off the table. Also because my ex and I, well, he's my ex. So, you know, when I was, got divorced and I had really custody of my children, that changed the

equation again. So perhaps if that had worked out, I might've done more traveling, but it didn't. And so, But I have no regrets in that regard. I feel like my musical life has been so very rich. And I know that for the people who do travel a lot, there's a sense of kind of rootlessness in the set. Like I was talking to a really well -known singer the other day and, you know, either I, I can't remember who asked her, well, where are you living right now? And she said nowhere.

And so I don't know that I would have ever been on that level, honestly, but. Yeah, that's not something that I think I aspire to anyway. So these are things that, you know, when I was a child, I really dreamed of like traveling all over the world and, you know, that sort of lifestyle. And I don't know that it suits me to do more than, you know, a few trips a year or, you know, I don't know that I would really have thrived

that way. It's hard to say, but I don't, you know, you can't rewrite the history and I'm grateful for all of the things that I have. I'm grateful for him. I'm grateful for my daughter, who's currently in Los Angeles, and I miss her a lot. And so for my particular path, I think the combination of things has been, you know, something wonderful. Yeah, wonderful and complicated too. And yeah,

yeah. Yeah. In the air, you know. Right. But it's not something that, as you said, uh you didn't expect or you didn't dream of and you know you thought of one thing and then the life just Throwed you a lot of different curve balls and it did but I think we all get curve balls though I mean whatever our choices and I i'm not one of these people who thinks everybody needs to have children to feel like a fully formed human You know, I don't believe that at all so

My particular path But maybe because you were sort of forced to be rooted in, I guess, you know, one spot or one town, then maybe that's maybe do you think that's that contributed to your creativity? Like you maybe you were more creative, creative person. But, you know, being creative, because creative person people are free in our mind, their minds, which means somehow physically. don't we have to be worded somewhere? Rather than? I don't know. Yeah, that's a good

question. I mean, I mean, you have to have you have to find time to do these creative things. And it's harder. I mean, I used to write things or do arrangements on the on an airplane, you know. I don't know that I'm so motivated to do

that now. So I think that for where I am now, it's good that I have, you know, I can get up and be in one place and I may have a number of things that I don't have to do when I leave town that are welcome things that I, you know, I'm like, oh, yeah, I don't have to wash the dishes and, you know, all these sorts of things. But um, For me personally, I think finding the time to do things and not having to think about, okay, I have to be here, you know, I'm traveling to

there. And I mean, I know of composers who go on retreats or writers or whoever, and they go on a retreat for a couple of days. And that's something that maybe I would be more able to do if I weren't still a caregiver. But on the other hand, you know, it hasn't stopped me from doing what I do. And so, yeah, I think. I think I think we can be creative. If we're truly creative in whatever the circumstances, we just figure

it out. Yeah. Definitely. Well, thanks for really opening up and telling me honestly about this. And but so lately, you know, I tend to save these questions a little later in the conversation, but I think it's important that we begin with this. So I kind of want to know your beginning. So you were born in Jamaica. raised in Canada and eventually moved your way to New York City to attend Julliard and the legendary George Sandor. Am I pronouncing? I mean, I think it's Sandor.

I tried to. I tried to pronounce his first name in the Hungarian way, and I never got it right. The GY eluded me. So he said, you can call me George. And I was like, well, that's not your name, really. But it was like Juj. And I'm sure that's horrifying to anybody who has. who speaks that language. But yes, Mr. Shondor, I think Shondor is correct. He's a legendary. I'm not pronouncing it right, that's all. So can you tell us about your upbringing? What kind of environment

nurtured your creativity? Sounds like you already have this innate, not just ability or gift of music, but also the desire. Yes. Well, my grandmother actually attended the New England Conservatory as a piano major. on my mother's side. So that was quite something back in the day. I mean, she wasn't there when, I know Florence Price was there. She wasn't there with Florence Price, but she, so that aspect in classical music was

on that side. Now, my grandmother had four children and I think after this, when she gave birth to the third child, she stopped practicing. My mother is the oldest and she remembers when she played and she remembers, you know, the performances. She lived in Bermuda and so, you know, my grandmother and my mother, but, you know, very much my grandmother always wanted me to keep playing. That was very strong. My grandmother taught piano. for many years and, you know, but she didn't really, I

never heard her play. And unfortunately, there are no recordings of her playing. I wish I'd been able to hear her. So my mother, got some lessons. She was the one who did the most with piano. And the thing was, my grandmother taught, but her children got sort of the last slots. And my mother was the only one who was really, really very interested in it. So my mother was my first piano teacher and she taught all I had for there were four kids in my family, and we

all had to take piano lessons. But I really wanted to. My brother was the oldest, and he was taking lessons. And I guess from the time I was two, I was asking for lessons. And yeah, I had to wait till I was four. And then soon after that, my mom said she decided to look for somebody else to teach me. I think I should know this. She knows this. I was six or I was eight. I can't

remember which. But anyway, I was still pretty young when I started taking lessons outside of the home and my sisters all continued and we all took lessons on I ended up taking violin for walks I fell in love with the violin and you know but it was always my second instrument I mean I started playing violin I think it was about 10 and I played until I was about 20 -ish

21. Anyway So my dad, from my dad's side, he was not someone who was into classical music when he was young and, you know, got exposed to it through my mom. And then he became, you know, he drove us to all the lessons and he listened to a lot of different kinds of music. Like the CBC is the equivalent of public, is the public radio station there. And driving to and fro, we'd listen to all kinds of things like, you know, Gaelic ballads and, you know, they just

had all kinds of music. But he also was very much into reggae and jazz. He loved the classic jazz singers like, you know, Sarah Vaughan, I think, was his favorite. But there were a lot of those ladies who he really appreciated. Nat King Cole, we listened to his piano playing as well. And they also listened to not huge amounts of gospel, but Mahalia Jackson was one, and Roland Hayes, we listened to the spirituals. So there was a wide range of musical styles played in

my house. you know, in Canada, you take history, music history exams as you take your piano exams and you know, your training. So it's all a system of things. So yeah, my so my upbringing, I was

very much exposed to all these things. And when I graduated from high school, was about to graduate from high school, I it was I was sort of thinking well maybe I should go into computer programming because that seems to be a more practical thing to do or whatever but then I knew that that wasn't really what I wanted to do and so I just decided that you know and I had my parents support that I was just going to go for it and go into music so it was a place where I mean there was a lot

of creativity in my house there was also every summer we were on the swim team and we didn't really practice the piano much during the summer. We didn't practice anything very much for at least two months and just like played outside and just did all kinds of you know kid things. I mean it was a time when you just ride your bike and then no one had a cell phone and you know to come home at a reasonable hour but the swim club was a lot of fun. twice a day for an

hour each. And so it wasn't like anybody was trying to be like, oh, you know, force you into doing it. Now, my mom did demand that we practice at least to some extent, but it wasn't OK, you have to practice for three hours a day or any particular prescribed amount. It was, you know, as our teachers would if the teacher said that you weren't practicing enough or, you know, there were certain things then we had to do more. But I got tired of being told, OK, go practice your

music. And it wasn't that I didn't love it. I did love it. But it was sort of like there were so many other things my brain was doing. So I think when I was about 12, maybe, or 12, 13, I was like, OK, no one is ever going to tell me to practice my music again. I don't want to hear it. And I just took it on and I became more serious. So I really A lot of things came easily

to me as a little kid. You know, I had good natural facility and tended to be musical and some of the attention to the details of things, you know, like really making sure that this technical passage was really worked out. You know, a lot of times

it would work. And I think I got more into that when I was about, you know, on the cusp of adolescence and really made a commitment And then when I was 17, I was in college, I was driving to college and I had a major car accident and I had a concussion. And before that, I never had any performance anxiety. It was just like, yeah, it'll be fine. But when I and you know, I would get into it.

I mean, I loved. I loved performing, I loved the music, and I didn't stop loving the music, but I had this concussion and then suddenly every once in a while I'd have a small memory lapse. And that was when my performance anxiety, you know, I started developing performance anxiety for obvious reasons, but I always loved being a musician too much to just you know, say, oh, well, this is a problem and I'm not going to

do it anymore. So I guess that really confirmed that music was really part of my core in every way. So. And where does this old writing and so many other ways of creativity come from the desire? I always wrote. too, like when I was a kid, I and you know, whether it was in school or there's some novels that probably will never see the light of day that may have been lost forever. And that might not be a bad thing that I wrote, you know, but I don't know. It was just

like I always had a lot of ideas. And I realized over the course of time of people asking me about being a composer that I I wrote little pieces when I was a kid too. I just, I mean, like there was a collection of four little piano pieces called Naughty Co -glypses and spelled like naughty, like a little kid being naughty. Tells of a kindergarten class that I wrote when I was like 13 or 14. And I did some light revisions later on when I was really thinking of myself as a composer.

And I had a teacher, her name was Lydia Pals, who said, you know, the first piece right in the style of such and such a person. And that's how they, she, and I think a lot of people teach you to compose things, but my brother was a filmmaker, even as a kid, he was very much into writing as well. He wrote, you know, like screenplays and he wrote other things. And so we'd organize this to do movies, like the number of kids and

we'd shoot super eight movies. And so we asked me to be like, the score, film score, you know, so when I think of it, I actually was making up things from way back when I just didn't, it didn't register something that I did, you know, when I was writing songs, I tried to write like pop songs when I was a teenager, too. And then it didn't. And somehow, you know, and those are that song writing, but I didn't think of myself as composing. And I don't know if it was because

I didn't know of women. or black women who were composers. And so just the legitimacy of what I was doing was something that was outside of, you know, what I didn't really it doesn't make sense looking back at it now that I didn't think I was composing. But, you know, it sounds like almost like it's like immediate creative creative

problems. So solution like you learn as a kid, you know, like your brother ask you to just compose something and then you're like, okay, you know, I'll just Yeah, well, I mean, I think it was because I was improvising and I played by ear. You know, I had perfect pitch and I would like, play things by ear all the time. And I think, you know, add things to them. So yeah, but it was it was a vote of confidence on his part. I guess it was like he was going to commission

someone to do these things. So If anyone was going to do it was going to be me, I suppose. Wow. But, you know, as early that your memory from that childhood is and how you are as a composer today, it's incredible, you know, the path that you took. And because I understand that you are you didn't study composition at Julliard, right? You know, studied. Yeah. But you know, I took this one class that the only other people in it were composers. And I think there was maybe

a flutist, but I believe I could be wrong. I think she dropped out. And the reason I took the class was because it was every other week. And it was in the morning, three hours every other week with Steve and Albert. And I thought, okay, well, I'll be able to sleep in every other week. So there was no, it wasn't, but it was process and inevitability in music, which I think, I mean, and the point was that some choices became inevitable in the construction of a piece, which

I never really understood. And I in the sense of inevitable, like, you know, so I had a problem with the premise of the class. But anyway, I mean, I felt like I was swimming most of the time, because I didn't know if I was getting on with what he was about. But I, you know, this is the only B plus that I was like, oh, wow, I got a B plus. But as I think of it, you know, I guess I was a composer in that class, too.

And it was more like analyzing compositions and trying to decide why the choice that the composer made was the inevitable choice. Just really, you know, philosophical to me stuff, but Yeah, but I never studied composition with him. Now, since I've become a composer, I've had people like Laurie Lateman and Juliana Hall and Jeffrey Ryan is a Canadian, really renowned Canadian composer and Evan Mack. I did a, it was like

a, not an internship, what am I saying? Like a mentorship program that the National Association of Teachers of Singing came up with shortly after George Floyd was murdered and they were trying to enable, it started off with black composers as giving us a platform and also mentors who could look at our compositions and give us, you know, some guidance. So I would say that certainly that was you know, a limited, not like, you know,

collegiate study, but it was something. And, you know, the mentorship that I had from Jeffrey Ryan through the Canadian Art Song Project, they commissioned me to write a piece and then they had, you know, asked him if he would mentor me through that process. Because I hate to say it, George Floyd's murder caused a lot of organizations to say, hmm, maybe we should take another look

at how we're representing Black composers. And I think, obviously, everybody, each group that is not as represented as they should be, you know, deserves that sort of, that sort of attention. But that was the focus right then. And so as a result, I was able to get a little bit more instruction. I'd already written some songs and I'm trying to think the timeline. No, I wrote

the piano pieces after that. Now the pandemic was actually pretty good for me on a creative sense, you know, because I, yeah, so I had more time. And one of the compositions that I was commissioned to write, and you know, YouTube has been good to me too, I have to say, because I just started posting things on YouTube. And somebody found me and wanted me to write a song cycle. for a young lady named Taylor Jasmine,

I think she goes by Jasmine White. And so it was commissioned by a university, Loyola University. And that was like, helped me, got me through, you know, financially towards the beginning of the pandemic that she found me and commissioned these pieces from me. Um, and then yeah, it was just like, I really felt, wow, God is looking after me. Because, I mean, like a lot of us were

sort of like, oh, what do we do now? You know, and then you figure it out that you can teach online and, you know, are you wearing a mask and all these sorts of things that we had to figure out. But I would say that I mean, I composed one of the more popular of my cycles grasping

water before the pandemic. But sort of that as a springboard to other things, you know, after, you know, to be honest, I didn't realize this composition thing came pretty recently, like, so 2020 is the time that you were able to devote yourself and create a part of your life. Like, me too, I started the show in 2020. So it was like a blessing. you know, in the skies, you know, it was difficult, but then I was able to really tap into who I am and what I want in my

life. Right. Yeah. But I didn't realize your composition. I mean, you've done composing before, but then. Yes, I did more arranging. And so, you know, going back into the 90s, I did, you know. choral arrangements, I was a church musician, I still am a church musician. And so I would sometimes do choral arrangements for that. And then in when, you know, my ex and I met at Juilliard and he asked me based on hearing a choral arrangement that I had done, if I would do some arrangements

of spirituals for his master's recital. And so I did that. And then Daryl again, Daryl Taylor. I shared with him Steal Away, which is one of the ones that I did for for Chris, Chris Corlewis, his name. And so I years later, he looked at it like he was handwritten. He got into a stack somewhere. And then he was doing a recording of spirituals and he found it and he recorded it. But then he also said there was a program, not a program, but I don't know what you call

it. It's sort of a call for people to write. music to words by County Cullen. County Cullen's poetry was in public domain. And so it was for the African American Art Song Alliance conference that he wanted to have this commissioning project, but we weren't getting paid, but, you know, just to write songs. And so he invited me to participate and I was like, well, I don't know if I can write songs. I know I can arrange things. He said, Oh, no, I think you could. I think you could

write. And again, this is me who had written these little things for my brother. And I had written these popular songs or they weren't popular because they never got released. But, you know, songs that I thought were on that vein. And I didn't have trouble writing melodies. So I don't know. It just didn't click like I just didn't think of it. Maybe it was the concussion and

I just, you know. But anyway, and 2015. So this song, Simon the Serenian Speaks, Darryl recorded it, or not recorded it, but he used it as the opening piece in a series of recitals he was doing in Spain and places in the States. And he told me he was doing this. And I was like, Oh, wow, I guess it was, you know, I guess that was good. You know, I liked it. But then I had this sort of intrigue already complex about,

you know, is this any good? And some of the songs, like I wrote three songs and I think the other two weren't as good. I know they weren't as good. But just the idea of going forward and having that encouragement of no, you can do this. And, you know, this is legitimate. And, you know, so for me to think of myself as a composer, even as taken several years, and a lot of positive reactions, and now, you know, I always thought,

okay, I like this, I didn't. feel like I needed someone else's permission for me to like it, but as to whether or not somebody else would like it. And now I'm sort of at the point that I'm not so much, I mean, it wasn't like I was writing them to say, well, I think people will like this or like that. It was just, especially if they're words, well, this is how I think these words need to be set. And that would be like, I think this needs to sound this way. And I would

go with that. Or sometimes, you know, I would consciously say, you know, I've been writing some things that are kind of slow. I think I'm going to write something that's more upbeat or something. But the mindset shift, again, it took a little while. And it's like, do I legitimately call myself a writer? And I was saying, well, I'm not really a writer, even though I was publishing. Things were getting published in Broad Street Review. I started looking for freelance things.

It was really trying to find. Well, how can I make a little more money? So, you know, they paid a little bit. And so I started doing things for us to get your view. And someone said, you know, well, you you're getting paid to write. So you're a writer. And to me, I go even further. I mean, even if you're not getting paid to write your writer, if you write, you know, it doesn't matter. You write and therefore you are a writer.

And whether and I think. This is sort of like the artist's way, which was something I can't remember who had introduced me to that. But the idea is that creating art is something that if you create it, you are a creator. Now what everybody else thinks of it is not necessarily the point. And if it's not good, then you have to be willing and able to go from not good to better. And that's how do you do that by continuing to create? So,

you know, will you get paid to do it? Maybe not, you know, and that for that, I'm eternally grateful. And that was not something that I was expecting, you know, but I still think that that spirit of I think I want to do this because this is something that speaks to me and I'd like to do like your podcast. I mean, that spirit. is something that I think, you know, everybody, everybody should dip into a little bit, whether it's just you create a new recipe, say you're not musical

at all, but you create a new recipe. Or let's say that you like to garden, I'm not a gardener, but you like to garden and then you create a beautiful arrangement in your yard. You know, I think creativity is open to everybody. And I think we're all better off for being creative in some way. especially after brutal 18 years of really difficult training, classical training we have, you know? Yes, and the thing is like, you know, as a teacher, I try not to, I mean,

I will guide you, obviously. But I mean, I try not to focus on well, there's a right way to play something. I mean, there are parameters that are established by the time period that

something comes from. so I'm not going to say no play that Bach like Rachmaninoff it's all good you know but um but on the other hand I think that you know I may very strongly feel that okay this is the way that I want something to sound because I'm very connected to this piece and I have a very definite idea of how I play it but I and I'll always preface that if I you know teach a piece like that it's like okay I have very strong opinions about this piece but

um you know so this is how i do it but i would like you to you know explore it yourself and in fact those are the pieces that i would demonstrate less uh than other things that i might you know be trying to show okay phrasing or something like that because i i want to leave some freedom. So but you know, it's true. I mean, and I wasn't somebody who did a lot of competition. But I think that that is also where you you know, people

and maybe it's less that way. I'm not really up on on what the parameters are as far as having a certain way that you play something and that's the way that it's supposed to go. And at least that's what Mr. Shonder told me back in the day he said, you know, to do well in competitions, you have to have first of all, like a height of just steel in the sense of how much you feel someone else's assessment of you affects your

own self worth. Because, you know, as he's saying, I mean, you can have people on the jury, and this makes sense. These people on the jury think this. a whole set of different people think that. And if you do something too creatively, then it's probably not going to win. And he said, you know, I'm paraphrasing, it's a similar example that, you know, he's been on a journey where

somebody reminded that. them of their some jurors, ex wife or something, you know, something along those lines, that they have some reason why they're, you know, against somebody that maybe has nothing to do with what they actually did, you know, and because they're all humans, right? They're all humans. So I don't know if the being kind of, you know, down the line with interpretation is still a thing and For him, he said also, I mean, you really have to be able to play these

pieces in your sleep. And so that means that you have to just keep working on the same pieces for, you know, long enough that you play them in your sleep as opposed to learning other things that, you know, maybe would allow you to explore

my repertoire. And, you know, and I was the kind of person who, like, if I got past the first round, then I would get freaked out by the expectation, my expectation of like, oh, my God, no, it's serious, as opposed to, you know, the first round is like, I'm playing these pieces, I'm just playing these pieces. And, you know, so I didn't have the mindset to do that sort of thing very well.

Hello, I'm Dr. Nana Ogwo, pianist and founder of Juneteenth LP, a Harlem based collective of black classically trained musicians dedicated to celebrating the music of the African diaspora through bold genre -defying performances that redefine what classical music can be and who is for. At Juneteenth LP, we believe in access, outreach, and community building through music.

Whether we're performing a rarely heard piece of music by a Black composer or reimagining soul and gospel classics or creating immersive education modules for schools, we're always expanding and growing audiences. When we play, we invite listeners into a richer, more inclusive musical world. This year marks a huge milestone for us, 10 years

of our Juneteenth celebration at Joe's Pub. What started as a single night of music and liberation has blossomed into a full week of concert and events, thanks to support from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the Aaron Copeland Fund, and Chamber Music America. We are thrilled to invite you to Juneteenth Festival Week 2025, a week of concerts and conversations across New York City. We kick things off with portrait of an artist event at Reservoir Studios in Midtown

Manhattan. and continue on with a Noonday concert at Interchurch Center, followed by date night performances at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Finally, on Juneteenth at 6 .30 p .m., June 19th, join us for our 10th annual Juneteenth Celebration Concert at Joe's Pub. It's our signature event where genre -defying performances, powerful storytelling, and a spirit of joy come together in one unforgettable night. We're also so excited to be sponsoring the June episodes of Yikimi Song's The Piano

Podcast, wrapping up season five. Pianists Dr. Leah Claiborne and Dr. Maria Thompson -Corley are incredible artists and educators with truly fascinating lives, and these interviews promise to be absolutely captivating. At Juneteenth LP, we center representation, cultural connection, and musical excellence. Whether through performances, education, archival work, our goal is simple, to make classical music more inclusive and more

expansive. We're reimagining what classical music can be by honoring its past, transforming its present, and opening doors for the future. Please join us on the 19th at Joe's Pub for a wonderful, wonderful concert. We know you'll enjoy it. Let's talk about your composition, your recordings. And I really, when I first heard your original,

was that 2020? workshop where you play the lucid dreaming oh yeah beautiful piece and then i also i know that in the uh album called soulscapes 2 yes you're not only the lucid dreaming but also willful ignorance yes i like the title and i almost kind of know what it means but so can you introduce us to your those two original piano solo pieces. Yeah. Well, I'll say blissful ignorance went along with willful ignorance, too. And the blissful ignorance is a very short piece about,

you know, literally blissful ignorance. Like you're just going along and pretending things aren't happening. And I mean, to me, the willful ignorance was more it was related to kind of anti woke things in the sense of, you know, I incorporate Go Down Moses in it. And so it's just sort of to me the bluster around, you know, everything is okay. And people are complaining

about something that doesn't exist. And so Go Down Moses keeps trying to break through and then gets a little bit longer moment towards the end and then it's just shouted down again by this, you know, like really bombastic ending. So, again, that piece was informed by, I can't remember if it was exactly George Floyd, but there were a raft, a raft of those incidents around that time. So that's what that piece was about. I want to actually perform this. Oh, sure.

Feel free. Yes, I think it can get the score from. What's the website? Cheap Music Plot. That's right. Yeah, I saw it. Yes, I would love to purchase and perform both of them. But I really like the title Wolfo Ignorance. I think really resonates with me as I am also grew up in. place where I was in the minority community and, you know, the voices are silenced, especially in my grandparents' generation, you know, being silenced is part of those, you know, a form of... Abuse, in many

ways. Oh sure, absolutely. So you really can see that and that affects generations to come and I witnessed, I experienced myself too. So the goalful ignorance, the title just really spoke to me. In the album also, you play Mother's Love by Emma Hoy? Yes. Gebru, is that how you pronounce? She was an Ethiopian musician. Right. Yeah, she died very recently, relatively considering she was 100 or I think, I don't know if she made

it 200, but she was almost there. Yeah, and such an interesting story that I had trouble actually finding music by African women. And I was told Rebecca Omordia, she runs the African Concert Series London. So the time that I asked her anyway, it weren't a lot of them who were breaking through. So a little patriarchal thing, I guess. But,

or at least in piano. But she started off wanting to be a concert pianist and she studied violin and then her family was quite well to do and then When Mussolini came in, then, you know, they were some of the people that were targeted. And anyway, she got in, I think she got in to the Royal Conservatory and then she didn't go.

And so there were some different accounts. I know that she ended up becoming a nun and I'm not sure she decided to become a nun instead of... making, becoming a pianist, but she did both and had quite a following, I've discovered, and the whole society dedicated to her and she used money that she made to help children. who were disadvantaged to have music lessons, and if you buy and make your scores, that's part of what the money's for. So, yeah, she lived

a long life. There was a BBC special called The Honky Tonk Nun, which is a really kind of bizarre thing, because her music sounds nothing like honky tonk. It's very idiosyncratic. And in fact, some of it has been used in... There was a movie called Passing, and one of her pieces was... sort of the theme music or the recurring piece. I can't remember the name of it, but, you know, in that and the after I recorded, I heard there was a Walmart commercial with Mother's Love in

it. It wasn't me. I had to listen to it a few times. I was like, OK, I don't recall anybody getting permission or getting any. royalties for this. But apparently, it wasn't I listened to it a number of times. And it's like, No, that's not me. I guess it maybe it was her original recording of it. But um, yeah, so she Walmart, Walmart, Walmart, I was quite surprised. It's like, Oh, my goodness. Somebody alerted me to

that and said, Is that you? And I was like, I hope not, because no one has gotten my permission to use up my recording. But Anyway, yeah, just a really interesting story. Really interesting journey that she had. And also, some of so there are so many wonderful pieces in there. But I care. Okay. Okay. Yes, in care. Yes. You put performed her dust and drums. Yes. Drums Calling, yes. Drums Calling, yes. Yes, sorry. Yeah, they're wonderful pieces. It's a wonderful composer.

of course, we talked about your first one, Soulscapes, which are including, you know, many other black composers, Viola, Kinney, Valerie Capers. Are they all female composers? Yes, all female composers. After I, you know, recorded Lesley's, the first etudes, somebody else recorded, Thomas Otten recorded the other ones. And I sort of decided I wanted to turn my attention to Black women composers and focus a little bit more on Black

women. Not exclusively, but certainly for those last two recordings, I feel like the first one was focused on the United States. and with the Price Sonata and the capers pieces. And then I wanted to open it up and look at the diaspora. So a number of the women are based in the UK, but have West Indian roots like Elna Alberga and Erlen Wallen and Shirley Thompson. No relation, I don't think. I don't think. But yeah, I wanted to make sure that I wasn't just focused on the

United States. Yeah, I also like love the piece by Dorothy Rudd Moore. Yeah, a little whimsy. Oh, yes. Yeah. Yeah. Well, she had the reputation of writing pieces that were very serious. And so that was deliberately written to show that she could do something lighthearted. For listeners out there, they can purchase CDs from your website

or how can they listen to your recordings? Um, actually, I think they're both like, I do have Soulscapes 2 in stock if they want to call me, get in touch with me directly from my website. That one's also available on Amazon. The first one, Soulscapes 1 is available on the website, Albany, the Albany website. I think they're now owned by Parma and Navona. I think they bought them out. So but anyway, I haven't checked to see if they've combined everything into one website.

But yeah, that was from Albany. Now, do you intend to compose more piano pieces? I'm actually thinking about like just in the preliminary stages of thinking about an idea that was given to me by Andrea Clearfield, who is a wonderful composer. And she was saying, you know, she'd be him aware of Malcolm's artwork and said, have you ever thought of composing pieces based on some of this artwork? And she has this in Philadelphia. It's called salon because it was a zoom salon.

And that was a live salon. And after the pandemic, it's a hybrid salon. So anybody in the world, and sometimes people from other places in the world participate in it. And so she said, you know, when you have a couple of pieces, then please bring them to the salon and with the artwork that they are inspired by. And I thought, well, that's a great idea, because it you know, exposure for my son's art and also be fun to write just some little pieces along those lines. So I'm

kind of focusing on other things right now. I scribbled down a couple like little motives for a couple of things and I'll probably continue

to do that. So I thought if I, I don't know how many I'm going to end up with, but if I end up with something that's like 15, even 15 minutes long, then I might try to pair them with, you know, Mussorgsky pictures, which I did way back in the day, which I I was thinking, oh, a few years ago, before she suggested this, I was like, you know, I think I want to take one more run of that before I decide I'm too old to go through that trouble. And then, you know, there's not

been a reason to follow through with that. But if I do, then, you know, that would be my hour long, you know, I'm not trying to add anything more than that. But yeah, I'm hoping, hoping that I can pull that off sometime relatively near. I mean, I have an opera that I'm writing for the Cincinnati Opera about John Lewis. And

that boy from Troy, right? Well, the title ended up being good trouble, the boy from Troy wanted to incorporate good trouble into it, since that's something that people really associate with him. So the piano vocal workshop is taking place in October, and then I will be back to working on

that. And there's a Yeah, so if you know, between the Performances i'm doing this summer and whatever else little projects and things that are happening in my life i'm hoping I can at least get a good start on those before the end of the year and Yeah, this opera sounds amazing. I know this is not the first time you wrote opera because you wrote the sky where you are Mini opera too, but did you even imagine yourself like writing opera when you are a young? No, this is incredible.

Well, um I just have a tendency to, you know, people give me a challenge and a lot of times I will just give it a try, you know? I mean, those sorts of challenges, you know, someone's, oh, it's up for you to skydive. And I'm like, maybe not. But that kind of tightrope, I'm willing to walk the tight, musical tightrope a lot of

the time. But so. The Sky Where You Are came out of some art songs that, again, it was pandemic era and there was a video thing of art songs and I had performed these art songs with a young singer who was associated with whoever was putting this together. Actually an opera theater is what

they're called based in Minnesota. So we recorded my three art songs and the director of an opera theater, Kelly Turpin, said, you know, I think that you could write this mini opera that they were doing for the Decameron Opera Coalition, which was put together during the pandemic, of course, Decameron being a reference to Tales Told during another pandemic long ago. And so these small to medium sized opera companies commissioned people to write, it could be no longer than 11

minutes. operas. They were supposed to be on stories from the Decameron, but she got dispensation to do one about domestic abuse during the pandemic when people were, you know, sometimes locked in with their abusers. And so a new libretto by Jenny O 'Connell, who had never written a libretto before, but she consulted with a local women's shelter and in Minnesota. And then That was what resulted was like I was asked to do this because she said, I think you could do this.

I think that the way that you approach art song is is like storytelling, I guess, or the musical way that I approached it. She felt like I could write an opera and it was just right for me to try it like two song, two singers, two instruments. That was all they could afford. And so it was a really great. entrance into it and, you know, a very meaningful project. And then I was asked to do when they did another De Carmen Opera Coalition the next year by a different opera company to

write something for them. And for this, I expanded it like they had a little bit more time. So it was 15 minutes. It was three singers and I could get up to four instruments and I have no piano this time. I decided I was going to go completely different route, partially because of the topic, which was about generational trauma established as a place like this beach that all black people end up on the beach and they're different generations of them. And this young woman has just arrived

and she doesn't know where she is. And so it's a very metaphorical thing. And they have to figure out how to get through. the situation and the answers together. But anyway, I decided that the piano wasn't something I wanted to use. I wanted to use a marimba, and I wanted to use a cello, and then I wanted to use a saxophone, like an alto saxophone, and then some percussion. So that was... starting to do more in the realm of orchestrating and with instruments that I

don't know. But having started my career in this so late, I know people who play almost every instrument and I have collaborated with people who have played almost every instrument in some way. So I could reach out to people and say, hey, you get a book that tells you. this is the range and this is the things to look out for. But then you talk to the horse's mouth and they can give you more insight. And, you know, you find out more and people were willing to look

at the parts and say, Yep, this would work. Or maybe you should do this here. Or I know that's not a good idea or something. So you know, that learning curve, so many opportunities that I've been given. And, yeah, it's really been like, I think divinely led, because I wasn't looking to do that at all. And then the other Yeah, and so getting to do, I don't know, I'm talking a

lot. Getting to do Good Trouble was because that first opera that I wrote, someone who I knew, Diana Solomon Glover, was a singer in New York at the time that I was in New York. And I learned from a mutual friend that she had written a libretto, I think her first libretto, and the piece was going to be performed at Santa Fe. And so I just reached out to her on Facebook and said, hey, congratulations on your first libero. That's

amazing. And I said, ironically, I wrote an opera, a first opera that I wasn't expecting to write. And so she was curious to hear it. And she liked it enough that she invited me to be part of this developing project. And I'll cut to the chase. So anyway, in the end, it was picked up by Cincinnati as a commission. And that's how that happened. Yeah, it's incredible. Having to have this knowledge of writing experience as a writer also helps put together a production like this, right? Yeah,

I think so. Yeah, it's a full circle moment. But I understand that you're, you know, I haven't read it yet, but there are novels by your choices letting go more than enough. Yeah. I mean, choices I wrote for fun when I was in grad school and Honestly, it was sort of an act of, I felt like I was reading stuff and I thought, oh, I could write that well. You know, I wasn't thinking myself a great author, but I was thinking I could write something as good as this, whatever it

was I was reading. And, you know, it was fun for me to create that story. And I sent it to, because at the time you had to send through the mail, Valentine and maybe a couple other places. And this lady wrote me back and said, you know, I don't have any room in my list, but I think that, you know, Essence magazine was starting up a series of books for black women, you know,

romance novels. And it wasn't really a romance novel, but it was, you know, there were relationships that were sort of the core of the core conflict was about relationships. So again, it kind of fell into. my lap that I got this recommendation, they were just starting it, I sent it out, they accepted it. And so that was published. And then after that, the next thing I wrote was actually more than enough. But they, they said, Okay, well, you're gonna have to get rid of the too

many relationships going on here. And there was a gay character who was a central character. And they said, Well, you know, I don't think you can have that this is in the 90s. So I said, Well, I'm not really willing to like get rid of these people. And I'm not willing to do that. And I wasn't setting out to be a famous author anyway. So that was fun. I'm going to just go

back to being a pianist now. And I don't know when it was that my mom suggested that something about, you know, writing something more about my own experiences, my own life, and letting go is not strictly autobiographical at all. Because half of it is written from the point of view

of a man. So I, you know, but There are outlines of things like it does have some Juilliard like the protagonist is a Juilliard trained pianist and she's at Juilliard and I was extremely shy when I was first at Juilliard and some of those things are actual stories and some of it is really not and so you know when they're aspects of my marriage again some of it's true some of it's not and so I would never say exactly what was true what was not. Well, some things I would

say, but not all of them. So anyway, that's where that came from. And then the other one, there was a Kindle thing where they were just having people you could publish whatever. And so I said, Well, I really like the story of more than enough. And so, you know, it's a period piece because it was very much written in the time of the 90s. And so I just put that you know, as a kindle thing. Now they have taken that down. Now they don't have you could buy episodes. And so I divided

it. So it's not really available anywhere anymore. But someday I may upload it. You know, you can do that. So I may. The great thing about, you know, these days as a creator, there are multiple ways to. Really put your materials out there like whether that is a video format Oh, I know you were also one time a podcaster too for a while Yes, I did. Yeah, you also have a extensive blog. I read a couple of them Yeah, yeah, there's

a lot. It's a lot Finding Beauty. Yeah, that was my that was my podcast but I mean I suppose the thing about it is if you have the attitude which I kind of skew towards of you putting it out there and someone may find it they may not find it and Then you know, I'll do it limited like I may post on Facebook or whatever and do a little bit of promotion and then you know gets limited audience and then other things so like if you put out a book, it's like either you're

saying again if someone finds that they may find it if not they won't but really to get any sort of traction with a book you need to really make an effort with letting go i i um sent it to various uh book reviewers and you could send it you know and they wouldn't ask you for money to review it they just wanted to get free books And so I got a number of reviews, you know, from people I knew, but most of them were from me doing a lot of work and identifying people and sending

them out. And sometimes they wanted hard copies, which means I had to buy hard copies. So, I mean, that's the thing. You know, if you want, you can put it out there, but no one will see it unless you do some other work to make sure people know about it. So it takes energy. It does in time. Yeah, sure. Yeah. But. It's fun being creative. Yeah, that's true. That's true. And once you started just for some people, it's just unstoppable,

right? Yeah, creative energy just yes comes up and yeah, in my case, I've had to like narrow things down a bit. Like I can't try to do all these things at once. I mean, there's a novel that I started. I think it was 2019 that I would still love to finish. But I haven't had You know, I haven't had time, so I may find a way to circle back. It's not something that needs to be current. So, you know, who knows? It's very inspirational hearing from you in person this way about creativity.

Yeah, it's encouraging to then that creative DNA is really handed to your daughter and your son and. Know we briefly talked about your family So I kind of want to focus on your son and can you tell tell us a little bit about your son? He is I've enjoyed looking at his Paintings and a drawing too. I like the pencil drawing of closet. Oh, yes It's so incredible. And they also I love his self -portrait. Oh, yes. Yeah, there's a

number of self -portraits. He likes to Yeah, he's he's I don't know if he's his favorite subject, but he's one of his favorite subjects, I would say. Yeah, I mean, Malcolm was diagnosed with autism when he was about three and he had the language delays and he still doesn't have a lot of expressive language despite a lot of different interventions and lots of speech therapy. So

he understands what you're talking about. um and um he you know he's the essence of him is just like he's very friendly and loving and i mean obviously no one's always in a good mood but you know um but the art thing. It's a whole other business. It's another one of those things. So he's had a number of exhibitions. He was selected one of 15 people from across the country actually in 2019. They had to be between 19 and 25 and he was just 19. He was the youngest one for a

Kennedy Center program. They have a number of things that are for people with disabilities and the disabilities ranged from you know PTSD to sight, you know, like having vision impairment and just different things. And there were two people on the autism spectrum in that class of 15. And they were supposed to have a nationwide tour of the art, but then the pandemic happened. So they had the art was just displayed at the

Kennedy Center and it was displayed. I arranged for one here in Lancaster and there were a few other stops, but they had to be cancelled. But, you know, he's had things that were published in like the Penn University Review or something. I submitted things internationally at there was a gallery in Toronto that had a show that, again, was delayed by the pandemic, but two of his pieces were exhibited there. But, you know, trying to maintain some momentum with that, again, it's

a job. And so I'm the person who does it. My sister is the one who designed his website, and she's kind of the webmaster in the family. And so, you know, I mean, I guess... The blessing with Malcolm is he doesn't have, you know, he's not like discouraged. He doesn't feel like, oh, no one's buying my art or someone is buying my art. I mean, he likes to think that people like his art. He loves it when someone says, oh, I love, you know, you're a great artist or anything

like that. He really enjoys that. But he's not invested in like, how is my career going kind of a thing? You know, it's very And it's not that he doesn't like to get paid for it, he does, but he's just as happy to go somewhere and get ice cream, you know what I mean? And just enjoy activities and whether or not people are investing in his art, he's not as focused on. And there are some things about his autism that I think

are really kind of a gift. um i mean he himself um anybody who has met him um you know he really is a gift he's just has a beautiful soul like and um even when he was in school you know um one of my daughter's friends had has a sister who was in his grade and so she asked you know does malcolm ever get bullied because he wouldn't necessarily have the words to tell me And I guess the sister just looked to her like, Are you crazy? Like, who would bully Malcolm? That's crazy,

kind of a thing. But I know that for kids on the spectrum, that's not necessarily a crazy thought, you know, but he, I mean, even in both high school and in middle school, some big kid just kind of took him under his wing. I mean, Malcolm is very tall, but he's very slight, like he's very thin. And I remember he wanted to go to all the school dances. He loves to dance. So, you know, I would take him to the school

dance. And I remember dropping him off. Someone had told me that this guy who was on the football team had really taken a liking to Malcolm. And, you know, just as like, you know, like, hey, buddy, you know, I saw him like, hey, Malcolm, how you doing? And good to see you and all this sort of stuff. And, you know, he just he just attracts goodwill. And, you know, that's just.

an incredible blessing. Even like the other day, we were in the grocery store and some guy was like, Hey, did you go to Hemfield High School? You know? Yeah, I think I mean, he didn't, I guess he didn't really interact. But it's just, you know, he has Yeah, there's something about him. So it's really wonderful. What a gift. And really, it shows in his painting and portraits too. I really like looking at them. Yeah, it's healing. So then, then you co -founded the Silence

Optional Concert Series with Sarah. Sarah and I started performing together as duo chiaroscuro when in 2011. And so the the name is a bit of a joke. And it's also kind of our approach to expression in that Sarah, her her mom is has Icelandic roots and Sarah is very blonde and I'm not. So I thought Kioskira was an interesting name for us. But somewhere along the way, you know, I can't always take Malcolm to concerts in that he may or may not be quiet in the way

that people expect him to be quiet. And so there was a quartet in Canada, actually, that had started these series of concerts. with that aim, and my brain is not functioning today. Anyway, I can't think of their name, but it's a string quartet, and so they would have, allow people to be in the audience who may be, you know, we're on the autism spectrum or whatever, and so we

gave a number of concerts with that. that you know if even I mean little kids could come as well and you know they were short like 30 -35

minutes they had a theme. The first ones that we did also had artwork for each piece that was created by Sarah's daughter and you know like whether she put together um some videos um or you know she didn't create original artwork but it would you know things would be images would be projected and um yeah they were um they were fun i mean we haven't been doing them lately she um isn't like completely out of the picture as far as being uh you know it's like an hour

or an hour and a half away but um just over the course of time we haven't been performing as much together But we, you know, as far as being asked to do those sorts of things, it's still on the table if people are interested in those programs, because they're very gratifying. And, you know, let Malcolm come to my concert and, you know, have enjoy because he really does enjoy all kinds of music and classical music. Wow, wonderful. Yeah. Now we're coming toward the

end of our conversation. Is there anything else? I have like two major questions to ask before we go but Is there anything else? I don't think so. I mean, we've covered a lot of ground. I don't think so Well, I mean Well, let me see what your questions are. Let me see your question. Oh one is the legacy what? kind of legacy you hope to leave. I mean, you're still very young, but you know, no, and then the second one would be what does true inclusion look like? Okay,

you know, so, yeah. So legacy is something that I can't really worry too much about. I mean, I'm just trying to do what I feel I need to do in the moment. I mean, when you have written things like compositions, you know, there's a potential that people will continue to perform them if you write a book or, you know, anything that I've put out there. Having done that means that there will be people and there are people who I've never met who've discovered these things.

And that's always a gratifying feeling to know that people appreciate what you were doing and what you've done. I can't be sure of what legacy will be because, you know, that's something that will be determined way in the future. And sometimes people forget about you, even, you know, people who are considered major composers of the day, and then, you know, people forget them. I mean, until years and years later, I mean, even, you know, Mendelssohn had to resuscitate Bach, you

know. So I'm not really going to worry about that. I just hope that, you know, I've used my time and continue to use my time on earth in a manner that is positive and, you know, I'm not trying to do something to undermine somebody else or, you know, just use it in a positive way and I can't really worry about the rest. And then the second question was about Sorry, inclusion. Yeah. Right. Like, is it all about just including the repertoire by, you know, composers

of color? But I think to me, it's more than that. But also, let's say inclusion also can be, you know, on someone on a spectrum. Right. Yeah, I mean, and that's another marginalized group is people with disabilities. Now, obviously, some things, I mean, Well, okay, my, my thought about true inclusion is that, first of all, to acknowledge that there was no good reason for us to be in this situation to even ask that question.

You know, I mean, the systems that were put in place to exclude, you know, I mean, it's been so elaborate and so long lasting. And, you know, we shouldn't even have to have these conversations because the parameters that have been used to judge and to exclude should not exist and make no sense. If you look at them, they make no sense. You know, so having gotten that out of the way.

I mean, it would be wonderful to have a day when there's not a conspicuous skewing in one direction about who is on the board of this and who makes the final decision about that. And in addition to, you know, the programming and seeing diversity represented in programming. And to me, like, you know, the people who push back on the idea of inclusion and equity and diversity, I would

have to ask, like, what is your objection? And if the idea is that, well, inherently certain things are not as good, because that has been sort of the idea, is that, you know, just making the assumption, well, this person did it, so it can't be as good, you know. The underlying logic there is non -existent. So I guess, I mean, the true inclusion would be when we're not thinking

about this anymore. you know, and it's not that we're not thinking about it anymore, because we don't want to think about it, or we're ignoring it. Yeah. Willful ignorance involved, or blissful ignorance. It's just, we don't have to think about it anymore. Because, I mean, it's just like the obvious thing that should have happened in the first place has happened. Now, will that

happen? You know, I mean, we can hope. we can hope it seems that I mean, it's not natural that when you get to a certain point of kind of knowing, I think, you know, you love pie. And whenever you go to the place, the cafeteria, you always get three pieces, and then the other 10 people have to split the other five, you know, well, I mean, if you really love pie, it's not the sort of thing that you're going to give up easily to say, well, You know, well, how come I'm not

getting my share of pie? There are eight pieces of pie and I always get three. It's like, well, should you be getting three? It's like, yeah, but I've always gotten three, you know, and I want I want three pieces of pie. So what are you going to do about that? You know, so I mean, that's the system. But I feel like, you know, there are enough people, hopefully, who are thinking about it and thinking, well, you know, that is kind of a lot of pie, actually, you know, and

get enough of those people. And we get to the point where, like I said, we're not thinking about it anymore. And everybody's like, that's equity. And diversity is because there are a diversity of people and you say there's no one who inherently doesn't belong. So that's where the diversity comes in. When you have these disproportionate things and inclusion, of course, is part of that. And, you know, the argument, I mean, without going on and on, and I'm going to just stop with

access does affect all of these things. And I don't want to pretend that that isn't also part of it. I was born in a family that could afford piano lessons and good music lessons and all kinds of things. And, you know, we can't expect everybody to give that away if you're a piano teacher. And so how important those who have the opportunity and the means to make access available. How important that becomes to those who could make up for the access that is not