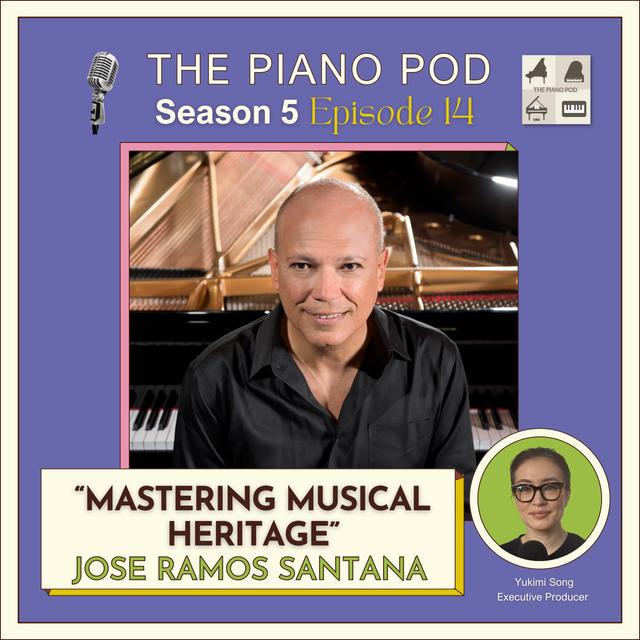

you Welcome back to another episode of the Pianopod, everyone. Today, I am thrilled to welcome José Ramos Santana, a pianist internationally acclaimed for his interpretations of Spanish and Latin American piano music. A Juilliard -trained virtuoso, José has performed as a soloist with major orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and has graced prestigious concert halls around the

world. His artistry and dedication to Spanish music earned him a special recognition for the Isaac Albany Medal, an honor acknowledging his contributions to the genre. In addition to his performing career, he is a devoted educator serving on the faculties of New York University and the Hart School of Music. In this episode, we'll explore the rich world of Spanish piano music.

What makes it so distinctive? how regional influences shaped its development, and the pivotal role of ethnomusicologist Felipe Pedrell in defining its nationalistic style. José will also share insights from his work with the legendary and late Alicia de la Locha, one of the greatest Spanish interpreters, and truly a legend among legends. Her influence on Spanish piano music is unparalleled, and we'll discuss how her mentorship

shaped José's artistic approach. Beyond Spain will take a deep dive into Puerto Rican classical music, a tradition that remains underrepresented in the broader classical world. José will highlight key composers, discuss the connections between Puerto Rican and Latin American musical styles, and share how his Puerto Rican heritage informs

his artistry. His journey from growing up in Puerto Rico to training at Juilliard and establishing himself as a leading concert pianist offers a fascinating glimpse into the life of an artist, navigating both tradition and innovation. As an educator, he continues to shape the next generation of musicians and will hear his thoughts on the evolving landscape of classical music and the challenges young pianists face today. Before we begin, I want to share something new with

you. Every Friday, I publish a blog on Substack where I go beyond the podcast, offering personal reflections, behind -the -scenes insights and thoughts on music, creativity, and the evolving role of classical musicians. If you enjoy these conversations, I invite you to subscribe at thepianopod .substack .com for exclusive content and deeper discussions. Now, let's dive into this incredible conversation with José Ramos Santana. Please

enjoy the show. You are listening to The Piano Pod, where we talk to the brightest minds in the industry about how they are bringing the piano into the future and thriving in a complex, ever -evolving world. Welcome to The Piano Pod, Jose. It's such a pleasure and honor to have you on the show. Thank you. It's my pleasure and my honor to have you as a host. Thank you for having me. Oh, of course. And then I know you're in like a New York tri -state area. Yeah,

in Connecticut. Connecticut. Well then, thanks. So thank you for joining me on this cold and icy February morning. You know, I've always been fascinated by Spanish music. It's instantly recognizable. You know, the moment you hear a piece by any Spanish composer, say, you know, Granados or whatever, even if you don't know the name of the composer, you know, that's a Spanish music. Right. Right. Yeah. And then there's just incredible fusion of folk traditions with regional diversity

and classical structures and then annex. Really expressive passion and rhythmic vitality. That's really, I feel like sits it apart. So I've also been really always drawn to Spanish culture in general and the language, poetry, and the cinema, you know, they have such a amazing cinematography list of films that they have. And then, so I really liked the. The way that these films really capture something raw and deeply human and emotionally

intensive, just like Spanish music. So today I am absolutely thrilled to explore the world of Spanish piano with you and someone who has truly lived and breathed this repertoire. And of course, I'm excited to talk about. Puerto Rican music and composers, which I am yet to learn. And this amazing music of your homeland. So let's start by getting to know you a little

better. So you've received numerous accolades and performed on some of the world's most prestigious stages and distinguished Steinway artists yourself. You are undoubtedly one of the most celebrated pianists. from Puerto Rico, but in your own words, can you tell us, if you were to capture the essence of your artistry, mission, and passion in just a few sentences, how would you define who you

are as an artist today? Well, I am an amalgamation of many things because my artistry, I was very privileged, very lucky to have had the last... I guess, part of the 19th, 20th century tradition of musicians, you know. When I was born, it was the time that Pablo Casals was in the island and he brought that, you know, his own tradition. Some of my teachers had studied in Europe before

the Second World War. So... Akin to the Spanish culture, two of my teachers have studied first at the Real Conservatorio de Música de Madrid and then to Ecole Normale, which was first founded by Alfred Cortot. So saying that, some of my teachers were... became very much influenced, and they studied with people like Ricardo Viñes, who was one of perhaps the most famous first interpreters of Spanish music, although he lived

in Paris at that time. And in Spain, they studied with, or they were associated with Fernandez Arboz, who was one of the notable... conductors of the Sinfonica de Madrid at that time. I think one or two of them studied with a lady called Lola Rodriguez de Aragon, who studied with Anton Rubinstein. So there was, you know, this influence. And the Spanish music was always a very strong... kind of definition in my upbringing. So therefore,

I think that I, and I loved it. So I think that my mission is to continue that with that old tradition. And of course, later on, I met Alicia de la Rocha and so on and so forth. As you said, the Spain culture and the Spanish tradition in me was deeply rooted. And so I feel that I'm a conduit for the new generation from this point of view. That's part of my mission. My mission is also to educate young generations of pianists.

And right now, for example... I started in Puerto Rico, Puerto Piano and Strings for Puerto Ricans and also international students to come to the island and just participate in this wonderful festival with international and national artists. So I think that this is what I want to make sure that... I establish, you know, as my legacy and as my mission. Also, again, I've been very fortunate and I'm very thankful for life. I've had great teachers in my background from Puerto Rico to

the end of my studies. They all carry a tradition that is lost. And so anyway, I feel that I am a link to that old tradition of artistry in the piano. Thank you so much for sharing. So speaking of Spanish music, so let's really dive into this wonderful world of Spanish music that is still yet to be played, should be played more often, I feel like. It's still the mainstream is the German and French school and the post -romantic of Rachmaninoff and so on. But Spanish music,

I feel like it's underrated still. Right. So Spanish music is often associated with flamenco and guitar, but there's so much more to it. Can you walk us through the diverse regional influences? Yes. For example, let's start from the north. You have typical dances. And, of course, the Basque country has their own language, but the Basque have their very complex rhythmic dances. One of them is called Sorzico, which, by the

way, Albanians wrote a piece based on that. It's 5 -4, 1 -2 -3 -4 -5, 1 -2 -3 -4 -5, 1 -2 -3 -4. It's a kind of unstable rhythm like that, but it's very beautiful. And then you also have the Galician. which comes from Gales and Wales and the British Isles, so that they also have their own musical language and dances typical of their region. Then if you go down, you have, well, to the east you have the Catalan, the Catalonian ones. Also, it's an amalgamation of Spanish and

French and Basque. Then you have Aragon, which you have the famous Jota, which you can find in this Spanish Rhapsody. That's the main theme is the Jota, from famous Jota. And you have Jotas also in some of the Albanian Iberia. You find the Jota in Malaga, the first of the fourth book. And then, of course, the ones that we know most as Spanish music is flamenco, the south, the Andalusian. And that's an amalgamation of flamenco,

gypsy, and... But there are also rhythms, for example, in Manuel de Falla and harmonies that are not flamenco. They are basically Moorish. So it comes from the Moor culture. which runs sort of, I guess, parallel to flamenco, but it dates even farther back than flamenco. So I think those are the ones, you know, different regions of Spain that you can identify as Spanish music. Those are the cultures, the general musical languages you'll find in the peninsula. Yeah, fascinating.

Yeah, as I was studying a little bit more about Spanish music for this episode, I'm learning a lot more. I've known Spanish music, the background of it, but just the historical background is so fascinating, right? Right, yeah, it is. So then I come across this name, Felipe. Pedro? Yes. Ethnomusicologist. I think he holds the key to this quote -unquote Spanish piano music because he's the one who influenced three big names you mentioned. Bernice... Granados and

the Fire. Can you tell me the background of this story? Do you know? Well, Felipe, as you said, he was an ethnomusicologist. And as an investigator, he delved into all these rhythms and cultures that the peninsula has had. And he encouraged Balbenes and De Falla and Granados to write in the style of Spanish language, of Spanish folk

music, Spanish tradition. So he was... a precursor of, let's say, Nadia Boulanger, that in the 20th century also she motivated all the composers that went to study with her from different countries to write in their own folkloric language, like

Copland or Astor Piazzolla, Bernstein. So he was actually, I think, the... the first one to recognize that the peninsula has a great cultural tradition in music and dance and it should be put into the composers pages you know it should be written down as music and and of course in the case of these people they were pianists and um so that's how they demonstrated uh they steal all the things through pianistic writing and at that time you know it was late 19th century

The influence of France, Liszt, was very much in vogue among everybody in Europe, pianist -wise. And so they wrote like this, in this Lisztian, super pianistic way. Right, right, right. But also, I remember these three big Spanish... composers, Albanese, Granados, Dafaia, they also spent quite a long time in France. Yes. I think that that was like the cultural center around that. Yes. So you hear the influence of French music as

well. Oh, yes, very much, very much. For example, I think the one that you can see the most of this in the Iberia street is Albanese. when he wrote it when he was living in Paris. And he wrote it as Impressions of Spain. I'm paraphrasing, but this is what he had in mind. And it was the publisher who said, you know, well, let's find a more marketing title. And why don't you call it Iberia? But again, Albéniz concentrated in the southern or the Andalusian rhythms of flamenco.

And distilled by the impression, I think he was a good friend of Claude Debussy. Claude Debussy admired his El Albacín, one of the greatest pieces written in that period. So he had this Paul Ducasse, all these composers at that time. had a distinctive influence. And thanks God, because I mean, his writing is just unique and phenomenal. He took the impressionistic and made it his own with this marriage of flamencos, Andalusian, Spanish

music. Absolutely. Yes. So for those who are listening right now, we're discussing about Isaac Albany's amazing. his masterwork, Iberia. Iberia has four volumes and each volume, each volume has three pieces. Correct. Right. But it's not the little tiny dance suite or anything. It's like each one has, is massive. Right. Exactly. It's also a piece in itself. Yeah. Oh my goodness. Right. Right. And then I know that you performed all of them. It's physically extremely difficult.

It is. Because the problem is that they don't get easier as the volumes progress. The most difficult is the fourth volume. And the more complex and the longer ones, like it is. It's very difficult. It's hard to keep the concentration, of course, the memory for that long period of time with so many notes that he wrote. And when he wrote it, he thought, I don't think anybody's going to be able to play this. It's unplayable. So there was a pianist called Blanche de Selva

that did play it. And she says, no, no, no, this is possible. It takes work, but it's possible. Really? Yes. Well, you know, personally, I did book three, all of them. Yes. But I didn't perform three of them back to back. There's no way I could do it. It was extremely difficult, but I fell in love with them immediately when I was introduced. So what makes this work really special for you? Yeah, I think it's my cultural background. My family, I was born toward the end of... My

mother was 45 when she had me. So she was quite old. And many of them were born when Spain was still dominant. Puerto Rico was a colony of Spain. And so that root of Spanish was always present in my family. And, of course, my teachers, too, when I developed. So that's what I felt so drawn. Also, Spanish music seems to be very happy music.

It's the happiness of the human race, the joy of living, and the enjoyment of this moment of cultural... ecstasies that we have because as you say Spain and it's so rich and so beautiful in so many ways but you know the southern part of Spain and Puerto Rico were very much alike you know there's beauty in Puerto Rico too and there's you know at that time you know as I said we were still very much influenced from with the Spanish culture in the island Yes. So I found

a voice with them, you know. And I was going to say, when you said before that the pianist education nowadays concentrates, well, I mean, of course, the base of the pianic education, as you say, the German, you know, romantic, even going back to Beethoven, Haydn. So every pianist has to do that. That's the background. That's the base. But there are other influences that should shape a pianist's view and education.

And let's start first with the French. You know, for a, you don't hear for a anymore, very little. And Debussy even is becoming not that popular. Ravel, some works because of their pianistic challenge. But that's another part of the pianistic development that has to be cultivated. The other one is, of course, the Russian music. Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, Tchaikovsky, and all the Russian. And that's also very, very important. And the Spanish.

Why the Spanish? Because the Spanish... Music frees your spirit to be very creative, but yet very disciplined. So you have to really learn to have a free spirit within very disciplined structures and rhythmic patterns and things like that. And that helps, because if you're playing, you know... I don't know, Chopin, all the Romantics, Liszt, and even the Russians too, Rachmaninoff. You have to have this free spirit in your playing, but yet it has to be very, very disciplined.

So all these things, all this culture, musical influence, share the same value from a different point of view, different perspective. And the more culture, I think the more you are exposed to as a student, you grow up with that. And I think it's great for the development of a pianist later on when they mature. They have all these resources to follow and fall on, you know. They are making up interpretations about. different styles and things like that. Absolutely. Yes,

yes, yes. So in this, you know, Iberia, all 12 movements, out of 12, 11 of them are sort of Andalusian influence. Right. And you mentioned you have such a deep sort of relatability or closeness to that culture. the Southern culture, but except for one, one is the, I think Lava Pies is not from the Andalusia. No, Lava Pies is a, is from Madrid. Okay. Yeah. Why is that

so hard? Yeah. Well, because if you, if you, Lava Pies is a, it was, but it still is called Lava Pies, but it was a kind of an ethnic ghetto. If you want to, describe it that way, where the gypsies used to live. But they intermingled with other cultures, Spaniards. So it was very, very typical. And then, of course, Madrid has their own personalities and their own type of, I would say, Yeah, characters. You have the characters of the guy and the girl, the chotis, the chotis

dance, which is very Madrileña dance. And, of course, the Paso Doble is also there. So, Lavapiés was what Albanians remember hearing all this confusion. It's a little bit like Charles Ives, you know. had all these memories when he heard, you know, all these evangelical hymns with parades and with, you know, other hymns from the Republic and everything together. And he, of course, in his own dissonant, highly complicated language, pianistically, contrapuntally. harmonically,

you name it. So Lavapiece is that type of piece, you see, that it sort of brings this confusion. I can imagine Malbec says, God, I remember all that. They had like a little organ that you just pumped like that. There was a little monkey that... kept dancing to it, and there was somebody asking for money, and then there was this florist selling the flowers, and there was all kinds of things

happening, very, very colorful. And he tried to write in notes all these dissonant sounds, all these clashing experiences, and that's why it is so difficult. Yes, it is. heard, you know, many, several performances. Well, one standout was a live performance by Yu Zhuang. She played beautifully. But some recordings, they played it so clean, too clean to me. It's just a miss, it missed out the cultural, like a little messiness,

in my opinion. Well, yes, because it's difficult, you know, you have to sort of make a choice but whether you're going to be very very clean or just emphasize the rhythm the one i think that is most satisfying is de la rocha because she has that rhythmic backbone with all this cleanness that she used to play with and it's fantastic how she does the proportions of sound and form and everything sort of works for her unfortunately the piece also lends itself to be bombastic.

And I think that's already distorting the idea that, you know, it's not bombastic. It can be bombastic because it's so huge. But that's, I don't think, what Mr. Albanis had in mind. It was just this super colorful writing, very complicated. And you have to sort of strike a balance between both of those. Wow. So speaking of Alicia de la Rocha, so first of all, what was she like? Well, she was the typical, you know, either Russian

teacher or, well, the Spanish grandmother. You know, she was like, you know, for her, her pupils were, you know, part of her and she took a personal interest in each one of them. development and their careers. And, you know, she was wonderful. Yeah. So you actually studied with her and she gave you love? What I did with her is I studied the Iberian. No way. Yes, I did. Wow. Yes. I think we did 11. There was one that I couldn't play for some reason, but we did 11 of the 12.

I worked here with her. How special. Wow. What stands out of all the probably advice you get? Yes. Well, it's very funny. I like to tell this story because when I first came to the Juilliard School, well, in the story with Adela Marcos, of course, she knew that I was from a Hispanic, Spanish background, and she emphasized that I should play this music. And at that time, I think I only have done maybe one of the debuts. And she introduced me to another one. Well, the Triana,

of course, and the first one, Evocacion. And she played Evocacion in such a convincing way when she was in the studio. Her best performance was in the studio. There she could play like you have never heard anything like it. What struck me was the understanding of the style that this lady had. She had never been to Spain, and she had never studied with somebody from Spain. She studied with the Levins, the Russian and German

school, Schnabel. And yet she was able to capture the flavor, the spirit, and even the rhythmic turns, and did it so well. that it just, I was in awe, you know, how she did it. I think she used to play also Andalusia from the Falla, again, in a manner that the other person I've heard play like that is Della Rocha. So when I went to Della Rocha, I played some of that, and Della Rocha said, oh, my God, you play very beautifully. Who was your teacher? So I thought, and then

she... De La Rocha called the Academia Marshall and told them about me and blah, blah, blah. But so starting with De La Rocha was like a continuation of what Marcus was doing. I remember doing once Albaicín with her. And of course, you know, sometimes you forget, you know, it's so complicated that you strive for getting the notes right and clean. And she said, no. No, no, no, phrasing, phrasing, phrasing. It was just like, listen to Adel Marcos teach. So it was very, very interesting, very

illuminating. She gave me some information about, you know, what the dances are, the integrated complexity of the dances. And, for example, she pointed out to me La Jota in Malaga, in the middle section. This is a hota, you know. And so you want to see what a hota is, you go download one of those YouTube videos of the dance in Aragon and you see what a hota is. But she was just wonderful, just wonderful. Wonderful to hear that. And so, you know, obviously, I have this

personal question. As I said, I learned a few from Iberia. And I often notice that his notation is quite messy on the score, even the ones that are printed on the print. I feel like some of the notes are wrong, wrongly notated, or maybe sometimes the accidental is missing. Well, yes, you have to be very, very careful. The only two editions that are... true to what the composer, Albanius, wrote. Well, the only one, really,

is the Urtext, the German Urtext. They have it, and all the notes in the Urtext are correct. This is a very interesting topic, what you just brought up, because with Beethoven and composers like that, it was very difficult. Sometimes he raised... wrote on top, and you didn't know what really the notes, what he meant. But with Albanese, when you see the script, you go to the Library of Congress, or you go to the Morgan Library of the Iberia, it's so clear. And how can editions

in France, like Durand, misinterpret that? I still, it's mind -boggling. I don't know what,

they did a very sloppy job sometimes. So, it took... somebody like de la rocha uh and and this to say look let's let's do a real good edition and she promoted uh you know the the real uh note correct writing and reading of the notes so i think she had a lot to do with with that in there by seeing there are a lot of wrong notes that she corrected she says no no this is not the original this is So, and of course, you have to really do what he did. You cannot really play

it as it's written. It's unplayable. You have to take things into hands. You have to, you know, and you have to voice them properly sometimes. So you have to make it easy. For example, when you take the one that everybody... It's so afraid, Tiana. There are ways of playing it that makes it more possible to play, you know, and in a way of not affecting the music and the music impulse or the music phrasing because of the difficulties. So if the arrangement helps that,

why not? Really? Yeah. But that's something that I have to learn from someone like you. Yeah. Yes, you have to rearrange many of those pieces. Della Rocha did too. She rearranged many of them. Really? Yeah. Della Rocha's hands were interesting because she had, they say small, but she had long fingers. So she was able to, you know, when you have long fingers, that's a plus, even though you have sort of a small hand. But you can do

many things with long fingers. I see. You have sharp fingers like mine, and that's more challenging. Joseph Hoffman had sharp fingers, too, and yet he was great and virtuoso. It's how you manipulate the piano. I see, yes. As De La Rocha used to say. That's interesting, and it's so true. Well, thank you for sharing all these insights about Iberia. I've always had big question marks about

interpretations and things like that. So just coming from you, especially studying with someone like Adele Marcus and then, of course, with Alicia De La Rocha's insights, it really just all of a sudden the music even comes more alive to me. Right, yes, yes. And, you know, as I said, my main teacher was Marcus, but De La Rocha, I only studied the... I videoed with her, but she considered me one of her pupils. I was like, honor. I said, well, thank you so much. Oh, no, my pupils always

mean a lot to me. So keep me posted of your career. She was so sweet. She was like a grandmother. Oh, wow. Yes. What a great story. Yes. Yes. Wow. So now, can we now move on to Granados? Yes. Granados, also you, played his most famous Koyaskas piano suite. So can you tell us what makes these series of pieces? Well, Granados was, you know, the improviser. All that you've seen in Page was improvisations that he did. No way. Yes,

everything is improvisation. he decided, or somebody I can remember decided, you have to pen them down, you have to write them down, because they're too precious just to left in the air. So he did. Goyescas is based on the opera Goyescas, which stems from Goyes painting. And so the style of Granados is much more conventional in the sense of... pianistic writing, you know, like more Lisztian, arpeggios and double notes and things like that, in a more clear way, not harmonically

as integrated. But there were two main influences in Granados' upbringing. That was Robert Schumann and Domenico Scarlatti. Oh, okay. Yeah. So many of his writing has this type of scarlatian clarity and bite to it, you know, with this very romantic, I guess, French salon style. But Amalga, the Goyescas is a throwback to classical Spanish

music, meaning from the classical period. Arriaga, composers like that, which weren't that many, but his tonadillas were all, you know, based on classical Spanish music, not necessarily a flamenco or Andalusian. It's different. I see. You have a piece called Zapateado, for example, which is, it's a part, Zapateado is, well, You have that later on in Latin America, in Mexico, zapateados means to dance with your foot in a particular manner and rhythm. So even the gauchos

have zapateados when they dance. It's like a cowboy dance, became a cowboy dance in Latin America, but it stems from the dance with the feet in Spain. Then you have pieces like Alegro de Concierto or Cenas Románticas, which is very much romantic piano music with a Spanish flavor. That's really what it is. And also, I must say that, you know, he was the founder of Academia Granados. He was a pedagogue. He loved to teach. Albanian was not much of a teacher, but he loved

to teach. And he lived in Barcelona most of his life after he came from Paris. And he founded this academia. He did treatises on piano playing, technique, pedaling, production of tone and sound. And it's very interesting because I read somewhere that he came to the same conclusions as Theodor Leschetizky did. in terms of approaching the

instrument. I don't think they knew each other, but it's interesting that they both found out this way of playing, this way of listening to sound, which is, you know, part of the old romantic pianistic tradition. Right, right. So that's why you have somebody like Frank Marshall. I was a great teacher and teaching Alicia de la Rocha. You know, she has this approach to music, the structure, the grandeur, the production of the sound, the pedaling, which is not taught

anymore. You know, people just put the things, they say it was by ear. Yes, but you have to train the ear to hear it properly, how to play it all. And it's a whole discipline. So Granados wrote a trilogy on pedal, how to pedal. Wow, that's interesting. So Alicia's teacher, Ms. De La Rocha's teacher was Frank Marshall. Frank Marshall studied at the academy, Granados Academy. Yeah, he studied with Granados. He was Granados'

pupil and assistant. And when Granados died, he, you know, he did continue the Granados Academy. Then he called it Academia Marshall. Really? Interesting. So with that tradition that Della Rocha had, and then now you have the tradition coming from her. That's very, very intriguing. So, I mean, there are more pieces that we can discuss, but I also want to... really get some sort of sense of the fire from your point of view, Manuel de Falla. And you've performed at

Nights in the Gardens of Spain. Yes, I will perform it next year again. Oh, wonderful. That's such a unique orchestral plus piano piece. Yes, it's a very beautiful piece. The orchestra sets a background of, I guess, I would call it Moorish impressionistic sounds and textures. The piano has more of the cantejondo, flamenco role, and rhythms also, also colored by this beautiful impressionistic and neo -romantic harmonies.

always, I think, considering the... He always had the sound of the Andalusian music in his ears, so he was able to write harmonically as he heard the sounds. But in Fantasia Betica, he uses some of it, but he goes back to the Moorish tradition, which with the quarter tones... and things like that. So he tried to imitate that at the piano the best he could, and it was quite successful. So to do that, do you use trills

a lot? You have to use pedaling. You have to be very careful how you pedal to create these harmonious overtones and blurs to give the impression of these overtones. this Moorish instrument gave. Wow. Yeah. He was also a musicologist inclined. He didn't write too much. He was a very ascetic man. He lived a very, he almost was like a monk. And of course, he moved to Buenos Argentina at the end of his life. But everything he wrote was so well planned and so well thought, you

know, that note, one note. was out of place. I see. Okay. Yes. Wow. I have yet to really learn his pieces. I've touched upon a little bit, but not quite. For example, the four Spanish dances, the first one, it's a jota. It's a real jota. The last one is a totally gypsy flamenco dance. the taconeado and things like that. And the other ones are, again, amalgamation of impressionistic Cuban habaneras. Very exotic. So the Latin American and Spain, later on, they fuse much more and

more. And so sometimes it's difficult to distinguish. For example, the best example is the tango by Albain. This tango and tango was brought from Argentina to Spain and to Europe. And Albanese immediately wrote this beautiful piece called the tango. That's true. Yeah, yeah, yeah. The PianoPod is now on Substack. If you're wondering, Substack is an all -in -one platform where creators like me can connect directly with you, share exclusive content, and build a thriving community.

By subscribing, you'll get behind -the -scenes updates, early access to new episodes, and special perks designed just for our audience. Your Substack subscription helps us create more of these meaningful conversations and support initiatives that uplift the classical music community. So join us on Substack and be part of this journey. Please go to thepianopod .substack .com. Thank you for your support, and I look forward to sharing more joyous and meaningful experiences with you on

the piano pod. Let's move on to the 20th century Spanish music, which you've done the complete piano violin works by Xavier. Montsalvage. Montsalvage, yes. It's very hard to pronounce. I know. It means wild forest. Oh, really? Oh, my goodness. Yeah, but his music is like a wild forest. It is like a wild forest. Yes, right? And he has this, some of that, I've listened to his solo pieces as well, and then has the sort of Afro -Cuban. Influences to? Oh, yes. There you are.

The amalgamation of Caribbean and Spanish music. And, of course, he took the poems of Nicolás Guillén, a great poet, and he sent them to music with these just delicious pieces, harmonies of habaneras and Afro -American, Afro -Cuban dance at the last one. It's just fascinating in the hands of a Spaniard. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Beautiful. So for my listeners, please check out Mr. José Ramos Santana's recordings of some of the pieces I mentioned, especially this Violin

and Piano Works by Monsalvache. Yes. Monsalvache. And then also you have other recordings, obviously. Oh, so yeah, I did. I recorded the Glossas piano concerto for a piano and orchestra with the Royal Philharmonic by my friend and colleague Roberto Sierra, a noted Puerto Rican composer who's having a great, great career to this day. Oh, that's

right. Yes, yes. I know the album. But didn't you also, record like concertos like Ravel concertos Ravel G and the Sansanji minor that's right they are incredible and then I can't wait to talk about Roberto Sierra but before that I kind of want to know your upbringing in Puerto Rico and then you know how you You discovered the love for music. And then, you know, later on, you moved to the United States and studied at Juilliard with Adele Marcus. So how was music introduced

to you? Well, I grew up with my mother from in my mother's side of the family. My mother went back to live with them and she took me. So since I was, you know, a baby. My aunts and my uncles, they all loved music. They weren't professional musicians, but they were amateur musicians. My aunt started voice with the great tenor Antonio Paoli, who was a very, very important figure in Europe in the early 20th century, late 19th

century. He even sang. under Verdi, one of the Otellos productions, I think, in Covent Garden. So my aunt loved music, loved opera. But my other aunts all took piano. My uncle loved music. They were founder members of the first Pro Arte Musical in the 1930s in Puerto Rico. That brought all the great artists, Segovia, Rubinstein, Claudia Rao, Jesha Heifetz to the island. They used to stop in Cuba and then in Puerto Rico. And so that was the background of my, when I grew up.

Then my next door neighbor moved to be a pianist herself, her daughter. And both, actually she started with this great pianist. She's known as Mexican pianist, but really she was born in Durabo, Puerto Rico, from a Puerto Rican father, Angelica Morales Fonsauer. And Angelica was a pupil of Emil Fonsauer, who was one of the least pupils. So I had that next door to me, this teacher who studied with her. I used to hear her practice. So I started because, of course, we had a piano,

and I used to hear her practicing. I used to go to the piano at my house and try to pick up by ear what they were practicing. So she calls one of my mothers. She says, wait a second. Is somebody trying to play the Greek concerto that I'm practicing? I said, oh, yes, that must be my son. So anyway, she said, really? I was four and a half years old. So she said, well, send that boy immediately to me. So I started with her. But I developed mostly with the Figueroa

family after a period of time. When I was seven, eight years old, I went to the Figueroa. And they were the ones that really, really developed me. Carmelina Figueroa, my teacher at that time, was... the head of the High School of Performing Arts in Puerto Rico, the Free School of Music is what it's called. And she studied in Paris. She studied à l 'école normale with all her brothers and sisters. They moved there, and they were under the umbrella of Cortot, Casals, Thibault.

They formed the Quintet, Figueroa Quintet at that time. in Paris, and if it weren't for Hitler and the Second World War, they would still probably be there. But then the Second World War broke, and they had to come back to Puerto Rico, and they started teaching there. So my teacher, it's interesting, because at that time, you had people like Dino Lipati, René Janoli, Gida Bakauer, that went through. through the Col Normalo study with Courtauld. But it was meant to be like a

pedagogy school, I was told. The Conservatoire of Paris always was performing. It was the Julliard of Paris. But Le Col was more to train good teachers. So my teacher studied with an assistant of Courtauld, Jeanne Blancard, and she was a great pedagogue. So she gave me a very, very good foundation. So when I went to the Juilliard school and I played for Marcus, she was like, wow, you really know how to play the piano. Who taught you? And

so I told her. And so when I went to Marcus, I had that already, you know, under my belt. So Marcus just really developed. and discipline and all of that. But I had a very, very good foundation, good training, good sense of musicality and ear for sound and all of that. Wonderful, wonderful. I was very, very privileged. But developing ear is like really the priority, the most important thing as a musician. Yeah, the most important thing. Absolutely. Wow. And what was it like

back in Juilliard days? Well, Juilliard, they used to call it a professional school. So it was a very professional school. It was a big shock for me, you know, coming from Puerto Rico to just be in New York at that time. But my mother moved with me. And the training that Adele Marcus expected was... She was very tough. She was a very tough, demanding teacher. And I'm talking later on nowadays with my colleagues, the ones who studied in Moscow, the Moscow Conservatory.

It was the same kind of training. You had to be able to, you know, have pieces. I remember I had eight works in one semester by memory. She demanded you have to have it by memory the second week. And it was really that type of training, like in all Russia. But that gave me a tremendous discipline. And, you know, later on, she was not the most easiest person to get along with. But later on, in the later part of her life,

we became very, very good friends. And we used to have a... laugh and dinners and we'd talk about music. She would hear me for hours and she would sit down and advise me and it was wonderful. Wonderful. And then your career as a soloist and recording artist flourished. Yeah, flourished. After that I immediately signed with Herbert Barrett and then I went to several competitions.

I was a finalist in the Bacower. Then I won an affiliate artist that gave me opportunities to play with many symphonies across the nation, including the New York Philharmonic, Detroit Symphony. Yeah, so that was a good St. Louis symphony. Good break in that time, my career. I was very lucky. So, you know, if you ask me then and now, it has been such a different, you know, what... young people's faces now. And that's from my time when I was at that age, at that

younger age. And it has changed quite dramatically, completely, I would say. Yeah, I think so too. Now, then... Maybe we can talk about that. You're an educator. You're teaching currently in Connecticut. It's a hard school. And also, you also teach at NYU as well? At NYU, I am, yeah, one of the artist faculty at NYU. There's such a huge difference between the time that you spend as a youth, as a young professional to now. Drastic difference.

Totally. As a musician, or young musician. they're all required to have multiple different skills, not just as a pianist. Yes. Time has changed. Time has changed, yeah. What do you see? Well, of course, the demands are different now, you know, from where I was. But I believe that the students, for example, when I was at the Juilliard School, besides piano, I took courses on... improvisation.

I took courses on accompanying, transposition, orchestral reading, many, many other things that prepared me to do things that I needed to do. I even took organ. So, you know, I was in a strand as a musician. I needed to play for a church once. I did it. You know, it was no problem. So the education I got at the junior was very, very valuable. I think we planted the seed. for what I have become. Later on, the best education I've really gotten is by teaching. I have learned

so much from teaching. I discovered so many things that has really been my education. So for my students, what I'm shocked nowadays is, I don't know, maybe... It was like that, but I wasn't aware. But, you know, they don't know the piano repertoire. I remember, just to give you an example, I had a student once who came from a prestigious Ivy League school with a prestigious music department, and I was shocked. I mean, things he didn't know. I said, well, you're a pianist, you never taught.

No, what a culture you have. I said, well, I think that... How can you be and not know those things, you know? How can you be a complete musician and not know the things, you know? And the same thing, you know, with the arts, you know, I was exposed to museums, to opera, to chamber music, to theater. They are not. They're just very much in the practice rooms and trying to win a competition. And this is very stifling because especially nowadays, if you don't win a competition, what

are you going to do? If you don't have all these other skills developed, if you want to be in music. So I insist on this well -rounded education to my students. And I provide them myself. I take them to museums. I take them to the opera. I tell them what to listen for. Yeah, I think this is very, very necessary. And it's lacking in their education. It's been given, but very, very lightly, very superficially, and not enough. It's not integrated. into their lives, right?

And it's not realistic, but as I say, because they only think in terms of competition. But if that, how many people can compete and win? One, two, three at the most? You know, that doesn't even guarantee a career. It just tells you, you know, a few years of concerts and then what? See? So you have to be prepared for that. Then what? You know, because that's going to be most of the time of your life. Yeah. And you have to be an entrepreneur. You have to know how to

become creative, you know. The classical music is challenged now by pop music, which is a great competition. So I think that in a way it's been our fault because we've been in such a bubble, you know, all the time that we don't realize there's a world around us. And we have to connect with the world and the needs of the world. And the needs have changed. So I believe in bringing classical music to everybody, not just an elite,

but everybody should be exposed. Because it's such a gift to just enjoy this great universal music. I hate to put it, classical music is a universal music. that bind us together and things like that. And I think there should be access to all kinds of economic, social economic levels, not just a privilege. Yeah, I know. And I see

that too. So even when I see, I'm raising quite a few young, small, but talented students, but then... they're so focused on the competitions because that's how the industry is right now. And not just a classical music industry, but I think in general, if you want to get into this school, that school, then you've got to win this thing or you've got to score this thing. It's not about being exposed to a different culture. No. When I went to school, I didn't go for the

school. Once Leo Fleischer told me, what do you think, Julia is gold? No, I didn't go for Julia for gold or for Julia because it's gold. I went to Julia because of a teacher. See, I wanted to study with that person. I wanted to get that legacy. Kids don't think this way anymore. They just think in terms of the names of the school. And that's unfortunate. That really is unfortunate because this, we're not in a, this is not, I mean, there's a certain sport. and commercial

aspect of our profession. But the root is art. And as Adele Marcus once told me, your career starts at the piano. Nothing else. If you're really good at the piano, if you're really an artist, life will take care of that. Life will take care of it. But you have to have that first. And this is what it's not, these young generations don't really have in mind. It's a little bit empty, hollow, their approach to everything. Yeah. And later on, yeah, they discover that.

I want to go back to your roots, Puerto Rico. So, you know, because I still want to learn about composers. You mentioned about Roberto Sierra, but I also know Gonzales de Jesus Nunez and then Adeline Cruz. So can you just tell us about this beautiful, beautiful music of Puerto Rico? So let me tell you my view of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico is a nation. What by saying it's a nation is that it has all kinds of music. I'm talking

from a musical point of view. So we have obviously the salsa, we have the pop music, we have what we know of Puerto Rican music, the Caribeños music, that it's universal now. But there is also a parallel world of... folkloric music that has not really been popularized. For example, the music from the mountains, the Híbaros, they have their own way of singing, which comes from the Canary Islands in Spain. As a root, you have the African, Puerto Rican population, Bomba and

Plena, which is also not known so much. Having mentioned those, let's say, three, and of course you have the European influence from Spain and France. Those music we had in Puerto Rico, polkas, we had in Puerto Rico, mazurkas, and all sorts of European form of music written by composers from Puerto Rico. I'm talking about the 19th

century. Many of these... composers like Julio de Arteaga and Manuel Tavares, I'm talking about 1865, 1870, 1880, went to France to study in France at the conservatory, or people from the conservatory. There was Marmontel, who was a very famous piano teacher at that time. I think

he was a pupil of Kalbrenner. And this one you mentioned, Gonzalo Nunez, who later moved to Cuba, and I think he died in Cuba, but he was born in Puerto Rico, started in Paris with George Matias, who was an Englishman who was one of Japan's pupils. Oh, I see. See? So he was supposed to be quite a virtuoso. I think he played in New York once in Aeolian Hall, a very old hall that doesn't exist in ages. But he settled in

Cuba. So he wrote music, again, with kind of Habanera rhythm, but very French Salon style, you see. Now, Tavares was, he stayed in Puerto Rico. daughter, Elisa Tavares, was a pianist and she became one of the, she was like the Rosina Levine of Puerto Rico in that time. And she studied with Isidore Philippe in Paris. And she studied, she played in New York too. She started an academy of piano in Puerto Rico. Many of the pianists of the early 20th century studied with her, Elisa.

But Manuel, her father, was the one. wrote Danza, La Danza puertorriqueña. It was the father. The Danza comes from the Cuban Contradance and the

Cuban Habaneras. People like Ignacio Cervantes, Saumel, wrote in Cuba Contradances and Dances, were just salon pieces with... a promenade for first a section then the dance the b section and goes back to uh this a well there's introduction a b a that's the format uh of the danza uh in the hands of cervantes was very very short maybe one two pages at the most in the hands of mr tavares in puerto rico he was three four pages long so he you know expanded the form of dances

and uh as i say danza means to dance but it also means to listen so it's like a masurka it's a combination of dance and song so you can sing it yeah so and and and and uh one thing about cervantes even though he was in puerto rico he was cuban he was living in paris At that time, he studied there, and he lived near Franz Liszt. And Mr. Liszt walked one day through and heard

this piano music, very weird, very exotic. So he knocked on his door, and Cervantes opened the door when he saw Mr. Franz Liszt in the footstep. And Franz Liszt came in, and he played some dances that he composed for Liszt. Really? No way. That's so cool. It's cool, yeah. But Puerto Rican dancers in the hands of Manuel Tavares. Then there was another Juan Morel Campos that came at the same time. He was not a pianist, but he wrote a lot of dances for piano. And Mr. Morel Campos never

left the island. Yet he was the most prolific and inventive. I mean, he had very, very... innovative way, harmonic even, to impart to the danza puertorriqueña. He wrote over 500 of them. Then in the 20th century, that tradition of danza has been still, you know, up to this day, I had a pupil of mine who wrote a danza. But it sounds like a danza rita by Richard Strauss. It's so chromatic and so, you know. But it still has that habanera kind of rhythm,

you know. The Afro -American, the Afro -Puerto Rican, Afro -Caribbean, and the French. So it's fascinating. So that's one genre that the Puerto Rican classical music has. cultivated. Then in the 20th century, composers like Hector, Campos Parsi, Amaury Veray, they were born in the 20s, so they got to study either in Paris with Boulanger or in the United States, Campos Parsi studied at the New England Conservatory with Adam Copeland, Irving Fine, and so they went back to Puerto

Rico. had positions of administrative and teaching positions at the conservatory in the government, and they wrote pieces based on other Puerto Rican folk idioms, like la bomba and plena, which is Afro -Puerto Rican music. Mr. Campos Parsi wrote a plena for piano that is very, very effective. written, the concert plan, he called it. And then you have somebody like Roberto Sierra, who was a pupil of all these people. And he was already a product of when Pablo Casals founded the Conservatory

of Music in Puerto Rico. And Roberto was a pianist. I remember him being a pianist and participating in student recitals. But then he decided to continue. as a composer. He went to Urdrecht in, I think, in Holland. He studied with Ligeti. And so he became one of Ligeti's students. And, you know, the rest is history. He has been very successful. Just now, Duda Mel and the Berlin Philharmonic play some of his music. He's been recorded by Deutsche Grammophon. And he's written a lot of

music for piano. He has, I think, 19 sonatas for piano. No way! Sonatas for piano, yes. And his writing has evolved tremendously. He also has the 24 preludes, based back in Chopin's preludes. Do you plan to play any of them? Yes, I've done some of the preludes, too. I haven't delved into the sonatas because they're very difficult. I haven't at the time. But I have some students of mine that I want them to study solo because they're really, really wonderful pieces. Yeah,

yeah. Very, very... But my genitives, they're very difficult, very complex. But yeah, they're wonderful works. I need to... get the score yes the score is available yes yes uh subito music i think is the publisher i think yeah yes yeah i'll check them out roberto sierra wonderful wow so i mean all these composers latin especially latin american music is underrated so that's why someone like amazing artists like you is promoting the music of Latin American music and

Spanish music as well. So, yeah. How is it going? Actually, I teach a course for graduate students in Latino American piano repertoire. It's part of piano literature courses at VANS. At Hart School? At Hart School, yes. We examine country by country. Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Colombia, Panama. So we take a good look into the composers that shaped the 20th century in those countries. And we're very, very fascinated.

For example, we just finished Chavez, Carlos Chavez, and Manuel Ponce, and the difference between both two composers. from the 20th century Mexican piano writing, it's really, really striking. Not to tell, you know, the ones that are now still alive that are very more on the aleatoristic style and things like that. So there's a great wealth. There's a great wealth in piano music in Latin America. We just know maybe the frosting of it, but there's a lot of other very... In

Argentina, there... You have Alberto Williams. You have, well, Jose Castro. Of course, Ginastera. And you have Osvaldo Goliov now. So, Richa, it's

another one that I'm forgetting the name. But there are a lot of composers that have written for piano music that is fascinating and is worth... discovering because it's very very well written and very and you know our ears have maybe 50 years or 70 years ago it was a little bit shocking but now our ears have the evolution of our ears is great has the capacity of you know absorb this music much with more intelligence and understanding and appreciated cultural aspects of them. Yeah.

Yeah. Wonderful. So, you know, as much as you've, you know, become this artist and, you know, gain your reputation and artistry worldwide, but seems like you are giving back. to your home country, your where, yeah, your heritage by doing a festival, the Puerto Rico International Piano Festival, but also promoting Latin American music as well. Tell me a little bit. I know you mentioned a little bit about the festival, but. Yes, I must give a plug on my festival. It's happening. We're

going to celebrate the 10th. Oh, wow. Congratulations. Thank you. It's held at the Conservatory of Music in Puerto Rico, in San Juan, Miramar, which is a beautiful conservatory. Thanks to one of my colleagues, Maria del Carmen Hill, who fought for it and got that building and transforming it. It was one of the 40 most beautiful conservatories in the American territory. And not only that, but it's a... Old Stanway School. No way! Wonderful! Yeah. So there are wonderful facilities for practicing,

for playing. The pianos are kept in tip -top shape. And it's usually in the summer. This year is going to be from June 22nd until June 30th. And we have a roster of wonderful artists. Eduardo Salim has been a part of it, Terry Njaparitse. We have had Pavlina Dokowska from Manus. We have had people like Andres Cardenas in the violin department, Amit Pellet, a great Israeli cellist.

So we do chamber music and piano. And of course, the Puerto Rican teachers like Maria del Carmen Hill, who's the head of the piano department. And this year we have Diana Figueroa Pabon, another distinguished part of the faculty from Puerto Rico. We have in the violin also the... Francisco Caban, who's a wonderful pedagogue, and Luis Miguel Rojas, although he's Venezuelan. He's been in Puerto Rico for many years. He was part of El Sistema, a great cellist and a great teacher.

So we also have Darrett Atkins in the violoncello department. He's going to visit us this summer from Oberlin and Julia. He's part of the faculty there. So we have Manuel Laufer, who specializes in contemporary music. So we have a wonderful, wonderful festival. Wow. Yes. And then age is targeting the professional age? It can be. If it's under 18, they need to be accompanied by a guardian or a parent. they can, you know, they can come. And, you know, and then grads, undergrads,

you know, students. Great. Yeah, I will make sure to list the link in the show notes. Yes, that would be great. Yeah, it's the one everybody goes, they love it because they fall in love with the history, the culture of the island, the performing facilities. And the teaching that is very intense, but it's excellent, excellent. I did this because there was a lapsus in where I hear my colleagues from Puerto Rico, oh my God, you know, the piano department is not what

it used to be. You know, we're not producing, we're not getting students. So there was a shift mostly for opera and there's a great voice talent in the island. I think the piano was a little bit abandoned. So I thought, well, let me see if I can infuse them with a new innovation of doing a festival for the conservatory. And it has created a lot of enthusiasm. And some of the kids from the conservatory have proven that they have come here. One of them is studying.

at the Eisler Conservatory School in Germany, in Berlin. The other ones has been here in NYU and Mannes. So we're beginning to see, you know, local students cross and become very, very competent pianists. Oh, wow. So that's, I'm very happy about that. Great. So is there any upcoming concert you have or any recording that you want to do? Let's see. Well, I'm supposed to go to, we're also working in Spain with Barcelona and Zaragoza, the conservatory. So I'm supposed to go there

and give master classes. I'm going to Shanghai, China. Yes, I was there last summer and had wonderful connections, especially the Shanghai Conservatory. And so that's coming up. My festival is coming up. And I'm playing the Knights in the Garden of Spain with the Puerto Rico Symphony of Defiance next season. So I have a few things to look forward to. So my audience can check out your website to get the latest news. Your website is at JoseRamosSantana

.com, correct? Absolutely, yes, yes, yes. Great. Well, it's been a really wonderful conversation. It's almost time for us to go. Thank you so much, Jose, for really joining. But before I forgot to tell you, we usually do a little rapid fire questions before we go. They are silly questions, but every guest has to do it in order for them to be dismissed. So I want you to answer them as short as possible. And they are really just a trivial question. So let's start with one.

First question. What is your comfort food? Oh, my comfort food is Puerto Rican food. Oh, yes. How do you like your coffee in the morning? I can't live without it. I cannot live without it. You cannot live without it. Puerto Rican coffee. Okay. Are you a cat person or dog person? Both, but I tend to be more cats. Summer or winter? Oh, summer. We need to get out of this miserable winter. Yes. Okay. Now, level two. What skill have you always wanted to learn but haven't had

a chance to? To be an artist, a painter. Oh. What is your word to live by or words to live by? Don't lose your focus and don't lose your faith. Great. What is the most important quality you look for in other people? Innate goodness, integrity, innate honesty. Name three people who inspire you, living or dead. That's hard. I know. Just whoever comes to your mind. Well, one of them is Mr. Casals, Pablo Casals. I admire him greatly. Great respect for him. My teacher,

Del Marcos, was a great, great influence. I'm very thankful for her. And the last one is, I would say, well, my mother. Wonderful. Great. So last question. Fill in the blank. Music is blank. Music is life. Beautiful. Great. This concludes the episode of The Piano Pot. A heartfelt thanks to you, Jose, for joining us today. Thank you. And then to our wonderful audience, you can learn more about Jose and his work by visiting his website at joseramosantana .com and start

listening to his incredible recordings. And then, of course, thanks to our... Faithful fans and listeners for tuning in today. If you enjoyed today's episode, please give it a thumbs up and subscribe to the PianoPod's YouTube channel. And don't forget to share and review this episode on your go -to podcast platform. I will see you for the next episode of the PianoPod. And thank you so much, Jose, once again. Thank you very much for your opportunity. It was a pleasure

to be with you. Oh, thank you, Jose.