Hello and welcome back to another episode of Surgery 101 brought to you with the help of the University of Albert. In this podcast I'll be talking about acute pancreatitis. I'll be discussing how to recognise the patient with acute pancreatitis and how to make the diagnosis. I'll also be talking about the pathophysiology of the condition and relating it to the management of the patient. So without further ado, let's proceed with the burning topic of pancreatitis.

okay so you're on call at night on the surgery service and you're asked to go acute pancreatitis. What should you expect to see when you get there? First of all acute pancreatitis is a pretty common cause of a pretty common surgical presentation which is acute abdominal pain or the acute abdomen. So most patients that you're assessing with acute pancreatitis will require pretty much the same approach as any other patient with abdominal pain.

Let's start off with the history. You want to get a good idea of the timeline, when abdominal pain started, where it was in the abdomen, if it moved anywhere else, what the character of the pain was, what the severity of the pain was. what the duration of the pain was and if there were any precipitating, aggravating or relieving factors. Usually in the patient with acute pancreatitis, the pain is quite particular. It is in the upper abdomen, usually above the amblytic.

Patients will often describe it as being in a band distribution and they may indicate that it goes around their upper abdomen. The feeling is typically a dull pain and it tends to go into the back. and it's fairly severe, it may be associated with some nausea and vomiting as well. Unlike other common causes of abdominal pain such as cholecystitis or appendicitis, it tends to be roughly in the middle of the abdomen. really to one side or the other.

It's often precipitated by eating. Typically it can occur after a large meal. and patients may have their supper and then go to bed and have the pen come on in the night. It can also occur after the ingestion of alcohol. Okay, so what should you look for when you're examining the patient with a good patient?

Because pancreatitis can occur in a range of severities, patients can look very well with mild pancreatitis, just a little bit of abdominal pain, and you're not that worried about them when you see them, or they can look really, really sick when you see them if they have severe pancreatitis. And we'll talk about why that is in just a minute.

When you're examining the abdomen you will probably notice some pain in the central abdomen or up in the epigastrium. Maybe some guarding in the upper abdomen as well. and with severe pancreatitis you may get guarding all over the abdomen to the point where the patient with acute pancreatitis looks exactly the same as the patient with perforated bone. generalized periodontitis with rebond, gardening and rigidity all over the abdomen.

So let's talk a little bit about the causes of acute pancreatitis because it's important to cover these in the history when you're speaking to the patient who comes in with pain like this. And acute pancreatitis is quite an unusual condition because there are a number of different sorts of causes. which all seem to lead to the same inflammation.

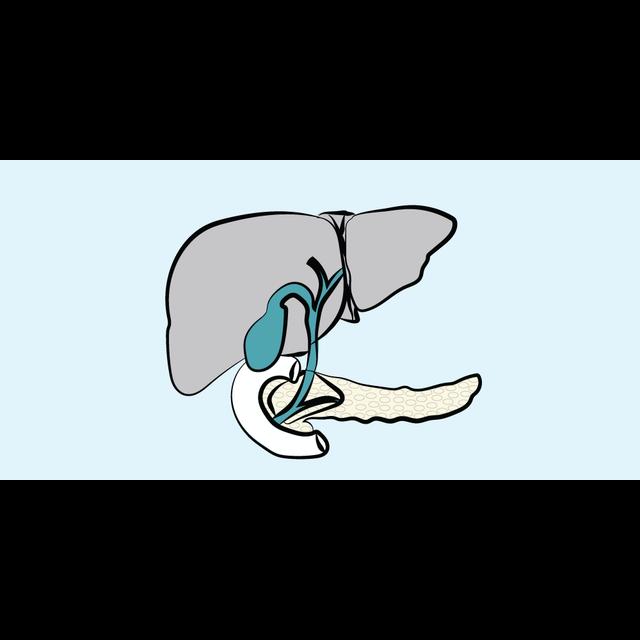

occurring in the pancreas gland. Probably the most common cause is gallstones and we think what happens is a gallstone leaves the gallbladder, comes through the cystic duct, it must be quite small to get through the cystic duct. then travels down the bile duct and at some point gets stuck when the bile duct joins in the pancreatic duct and we think there's some sort of backup there.

within the pancreatic duct which causes inflammation in the pancreas. The next most common cause I would say is alcohol and we're not sure why some people who digest alcohol get pancreatitis but it seems that there is a connection between. ingestion and the condition. So it's important to take an alcohol history from the patient.

So alcohol and gallstones are the two most common causes. But there are a bunch of other causes. You can have high levels of calcium in the blood hypercalcium and it can cause pancreatitis. You can also get it with hypertriglycerinemia. You can also get it after trauma to the abdomen. If you have some traumatic injury to your pancreas, you can get a traumatic pancreatitis. You can also get it after ERCP. This is probably related to instrumentation of the pancreatic duct at ERCP.

You can also get it after a viral infection such as mumps. There are congenital causes of pancreatitis such as pancreas divisum. And there are drugs that can cause pancreatitis. such as steroids, diuretics, acythioprine and some of the anticonvulsants and chemotherapeutic agents. There's also a hereditary form of pancreatitis and pancreatitis can be associated with porphyry. And last but not least is the medical student's favourite cause, which is scorpion venom.

I know training in the UK, we use the acronym GET SMASHED to remember the common causes of acute pancreatitis. And this stands for gallstones, ethanol, trauma, steroids, mumps.

autoimmune, scorpion sting, hypercalcemia and hyper triglyceridemia and then lastly ERCP and drug It's important to note that even with this long list of possible causes of pancreatitis, In about 10 to 20% of cases, the cause for pancreatitis is not clear and the patient doesn't appear to have any of the risk factors that we have just discussed.

But thinking about the causes of pancreatitis is quite important. If we can figure out what the cause is, we are able to try to prevent further episodes of pancreatitis. And we'll talk a little about this when we talk about management. As a surgeon, I sometimes say that I think about acute pancreatitis like it's a fire burning within the abdomen.

And sometimes it's a small fire and it smoulders for a few days and it goes out. And other times it's a big fire and it spreads to other parts of the body. You think about where the Pythagoras is, it sits in the Rhettoperitonium right in front of the major vessels. And when the pancreas becomes inflamed, there is significant release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines into the circulation. And it's this that causes what's called a systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

The inflammatory mediators which are released into the circulation cause problems with other organs in the body. You may see evidence of respiratory failure. You may see evidence of cardiac failure. You may see renal failure or liver failure or problems with the coagulation system, all based on the fact that the inflammatory response has been triggered by the acute pancreatitis.

And you may see this in the patient with acute pancreatitis. They may have a high pulse, a high temperature, a high white cell count, and a high respiratory rate. All of those things should get you thinking this patient is pretty sick. And perhaps the signs you're seeing are indicative of a major systemic inflammatory response syndrome. I would say that of all the different organisms that can fail in acute pancreatitis, respiratory failure is the most common.

It's very common to see pleural effusions in association with acute pancreatitis. And in intensive care, you may hear people talking about ARDS or acute respiratory distress syndrome in the patient with severe acute pancreatitis. So let's talk about how we make the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and how we decide how severe it is. As I mentioned a little while ago.

The first step in making the diagnosis is to have a high index of suspicion, take good history from the patient and examine the patient. and the patient will have this upper abdominal pain like a bad going into their back with some upper abdominal pain in it and there may be some risk factors in their history such as alcohol or drugs perhaps. They may have had recent trauma or a recent ERCP. Or perhaps they had mumps recently. Maybe they were bitten by a scorpion.

The key to clinching the diagnosis is to get a serum lipase blood test, which is called an amylase in the UK. And usually with acute pancreatitis, this is diagnosed. The lab in the hospital where I work quotes values of lipase up to 300 as being normal and typically with a patient with pancreatitis I see values between 5,000 and 25,000 so it's a pretty significant lipase rise. I would go so far as to say any patient who presents with an acute abdomen should have a lipase down.

And I've almost been caught out a few times over the years where I've seen someone who I thought had a perforated bowel perhaps or I thought had peritonitis and I was thinking of taking to the OR for a laparotomy and it turned out they just had pancreatitis.

And as you're going to hear in a minute, the primary treatment of pancreatitis is non-surgical. And typically we don't like doing laparotomies on people with pancreatitis without a good reason. So I would suggest you do a light pace on every person who comes in with an acute andaman. So the diagnosis is largely clinical and biochemical. It can be supported with imaging and often people with pancreatitis will get an ultrasound or a CAT scan in the first.

24, 48, 72 hours after admission. And ultrasound is useful for showing if there's gallstones. And the CAT scan can be useful for identifying pancreatic necrosis. And it's not unusual to have free fluid in the abdomen with a severe pancreatitis. It's quite important to try to figure out how severe the episode of pancreatitis is.

And there have been a number of ways suggested of doing this. The key concept that they all have in common is trying to detect signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and early organ failure. There are a bunch of systems that have been used to assess the severity of good pancreatitis. There's the Apache criteria. There's the Ransom criteria.

and the Glasgow criteria. And these look at things like the white blood count, the blood glucose, the serum calcium and other markers like the serum urea and the arterial oxygen concentration. I won't go into the details of each system here, but if you're interested they're all available online. In recent years though, attention has shifted more towards thinking about acute pancreatitis as being associated with organ failure and looking for early signs.

organ impairment, so looking for hypoxemia and tachypnea in respiratory failure. looking for tachycardia and perhaps hypotension for cardiac failure, looking for an elevated creatinine or urea in renal failure. looking for problems with the coagulation, looking for elevations in the liver function tests. And if someone has mild pancreatitis, they're going to settle in a few days. Then they typically don't have any signs of any organs.

If someone has moderate or severe pancreatitis, they will have signs of multiple organ systems being impaired. And it's this type of patient with moderate or severe good pancreatitis. who may end up being treated in the intensive care unit for support of their impaired or failing organ system. So let's talk about the treatment of the patient with acute pancreatitis. Let's focus firstly on the patient with mild pancreatitis.

These patients will typically get better over a few days with supportive, conservative treatment. This means they may not eat for a couple of days. They get some intravenous fluids and some analgesia and the pain gradually settles. And this is perhaps the most common sequence of events with acute pancreatitis. Once they're feeling better again, it's important to consider the cause of their pancreatitis and to try and treat this cause so that they don't get any more attacks like this.

We need to check if the patient has gallstones or not, because if they do, they should probably have a cholecystectomy to try and prevent another attack of gallstone pancreatitis like this. Traditional teaching would be that that cholecysterectomy should be done on the same admission as the attack of the acute pancreatitis.

If you have rapid access to a day case cholestectomy, it is reasonable to discharge the patient for a few days or perhaps a week or two and then bring them back for surgery after that.

and this is really because you don't want a second attack of a good pancreatitis to occur even if the first episode was mild further episodes can be more severe so it's important to proceed quickly and take the gall banner out and prevent further With regard to the other causes, you may advise the patient to avoid alcohol or to stop certain drugs that they're on if you think that's the cause of this attack of pancreatitis.

So what about the patient with moderate or severe pancreatitis? It's important to identify these people early by looking at those early signs of organ dysfunction. It's important to have them in an appropriate environment of care, such as a high dependency or an observation unit. And if their organ function gets worse, it's important to involve the intensive care team quickly in case they need ventilation or cardiac support or dial.

Usually, moderate or severe pancreatitis does take longer to resolve than mild pancreatitis. But still, the main step treatment is conservative and supportive. supporting organ function, treating organ failure and preventing complications such as infection. I'm not going to talk a lot about the surgical treatment of pancreatitis.

largely because the indications for surgery in acute pancreatitis are pretty small and most people with pancreatitis don't need an operation unless you count removing their gallbladder in the case of gallstone pancreatitis. Really surgery is reserved to treat the local complications of severe acute pancreatitis.

These are infected pancreatic necrosis, pancreatic abscess and pancreatic pseudocyst. And I'll talk briefly about each of these. It's fairly common to see pancreatic necrosis in the patient with severe acute pancreatitis. And in the stable patient with pancreatic necrosis, this is not by itself an indication for surgery.

If the patient is unstable and their organ failure appears to be getting worse, then sometimes doing a necrosectomy, which is an operation to debride or remove dead parts of the pancreas, can improve the situation. And this is especially relevant if there's evidence of infection around that dead necrotic patient. And really it's exactly the same argument for that second indication of maturity, which is pancreatic abscess, which is quite an uncommon but very serious condition.

I've never seen a case of pancreatic abscess, but traditionally we talk about the mortality from pancreatic abscess being... So really those first two surgical approaches to the pancreas are designed to get rid of dead, infected pancreatic material, which is making the patient's organ failure worse. The third operative approach to the pancreas is for... complication called Pygredic Pseudocest.

and this is a large fluid collection that gathers in response to the inflammation in the lesser sac which is the space between the pancreas and the back wall of the stomach. It's pretty common on the imaging to see a collection of fluid in the lesser sac in association with acute pancreatitis, but most of these fluid collections are asymptomatic and resolve on their own. Sometimes, however, that fluid collection does not go away and it persists.

And that's what a pseudocyst is. It's called a pseudocyst because it's a fluid filled space which is not lined with epithelium and therefore is not a proper Really it's just a large fluid collection in the lesser sound. Often the patient will have ongoing upper abdominal pain or not be able to finish a full meal because of the pressure on their stomach.

So if the flu collection persists and the symptoms persist, this is treated by performing a cyst gastrostomy which is making an opening into the back wall of the stomach to evacuate the cyst contents into the stomach lumen. Let's review the key points you need to remember for the patient with acute pancreatitis. Think about the typical history of a patient with recent ingestion of food or alcohol with acute onset, upper abdominal pain, like a band going into their back.

Don't forget to consider the diagnosis in anyone who presents with an acute abdomen. Don't forget to ask about causes and risk factors. Use your mnemonic, get smashed. Gallstones and alcohol are the two most common causes, but don't forget about the other ones, like drugs, viral infections, triglycerides and calcium. Think about pancreatitis being like a fire that spreads to other organ systems in the body with a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, organ dysfunction and organ failure.

The serum lipase is diagnostic and may be supported by imaging. Management is largely conservative and supportive but there are some indications for surgery such as infected pancreatic necrosis, pancreatic abscess and pseudocyst formation. Once the patient is better again, don't forget to treat the cause of their pancreatitis. If it's alcohol, get them to avoid drinking. Consider stopping any funny drugs they're on. And if it's gallstone... Remove the Gold Ladder to prevent further attacks.

So, that's a medical student's basic guide to acute pancreatitis in 20 minutes or less. Thanks for listening to Surgery 101, and I hope you enjoyed this podcast. Please join us again for our next episode. If you have comments about our podcasts or suggestions for future topics you'd like us to address, please visit us at surgery101.org