Hallo, beautiful neighborhood.

I had a fresh new episode ready for you for today, but I saw on Facebook Memories what a marvelous invention that it's been one year exactly since one of our most popular episodes ever, so it felt like a nice time to bump this one back into your ears, especially with so many of us still in lockdown. I personally loved the escapism of going back to this one again, so hopefully some of you do too, or if you missed it the first time, it is one of my

favorites ever. Please ignore any time specific references, although most of our ya is evergreen, so hopefully you enjoy it as much as I did the first time, the second time, and probably the third time that I've listened to it.

I truly soak this one up, as you guys can tell since a year later, I'm still banging on about it, and I'll keep this week's fresh episode for you for next week, which is also a banger you might have seen on socials that We very very closely followed the amazing Jess Fox's Gold Metal performance in Tokyo this year and was so lucky to be able to sit down with her while she is in we are preparing for the World Cup to chat about that experience, Her Way,

Toya to get there and everything else in between, which I'm so excited to share, So make sure you've subscribed to get that one as well next week.

When it drops, the water is like coffee. You cannot see your hand in front of your face. So that must have been just horrific swimming through that water waiting to find all these bodies. When suddenly these lights came on and one by one all these boys started running down the hill. Of course, the whole world suddenly went, yeah, they're saved, you know, no worries, But anyone who knows anything about caving and cave diving went, oh my god, what do we do now? There are risks out there,

but without risk taking, we don't become resilient. We don't become confident. We have to do things that challenges and can be hard or uncomfortable. If you think you're no good, it's something, the best way to fix it is to just do it.

Welcome to the Seas the YA Podcast. Busy and happy are not the same thing. We too rarely question what makes the heart seeing We work, then we rest, but rarely we play and often don't realize there's more than one way. So this is the platforms to hear and explore the stories of those who found lives they adore, the good, bad and ugly, The best and worst day

will bear all the facets of seizing your Yea. I'm Sarah Davidson or a spoonful of Sarah, a lawyer turned funentrepreneur who swapped the suits and heels to co found matcha Maiden and matcha Milk Bar. Sez the Ya is a series of conversations on finding a life you love and exploring the self doubt, challenge, joy and fulfillment along

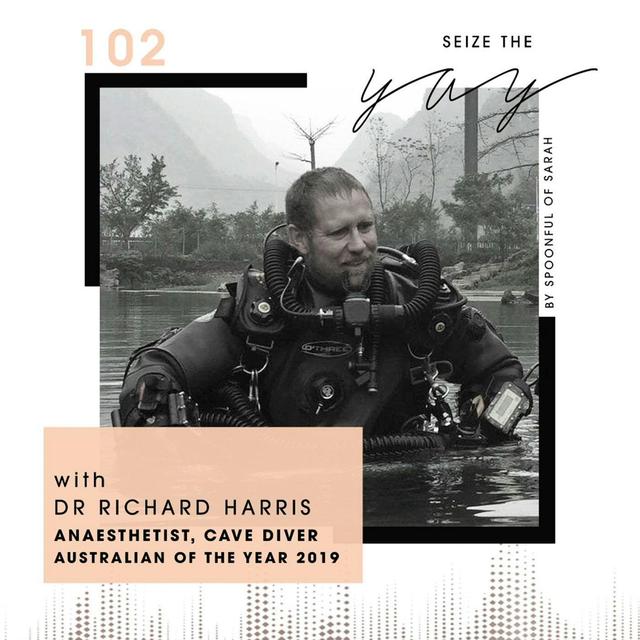

the way. Sometimes I choose our guests out of purely selfish curiosity to converse with a particular person, regardless of whether anyone else would find them interesting, although I suspect most of you will be as fascinated by doctor Richard Harris as I am.

After a random.

News article led me off on a multi hour internet tangent a few weeks ago, I bought doctor Harris's book against all odds and got it in my head that I had to talk to him, and I'm so glad He very kindly agreed to.

Jump on the show.

You know, I get overly excited about the unique way our talents and interests can intersect to create a yayfield life. And Doctor Harris, or Harry as he insists I call him, has a truly unique set of skills as an anthetist and technical cave diver. I'm pretty sure I said that wrong. Aneseotist,

a nethetist anyway, you know what I'm saying. So unique, in fact were his skills that he was pretty much the only person in the world equipped to help sedate and thereby save the thirteen young Thaie boys of the Wild Boars soccer team who got stuck four kilometers into a cave in Thailand in the rainy season of twenty eighteen, along with diving mate and co author Dr Craig Challon, with whom he won Australian of the Year last year. I don't think I need to say much more to

explain why I'm fascinated by historian skill set. I gush a lot in this one, but I just couldn't fathom the enormity of the task before him, the details of which definitely went over my head watching it on the news at the time, among many other things. Harry also has his own wonderful podcast, the Real Risk Podcast, so was equipped with a proper mic, such a pro so that'll be a nice little break from our guest zoom audio.

I highly recommend both his book and his podcast, the latest episode of which is actually with the legendary James Cameron of Titanic fame. I'll include links at the end, and I hope you enjoy doctor Harris, even though you very humbly told me I was only allowed to call you that once. Welcome to the show.

Are you welcome, Sarah?

I am so impressed. You have such a good setup going there. You're the first person in a long time who's had a professional mic.

Well, we're both professionals here, and we've both chosen the same microphone, so we're off to a good start.

Great minds.

So we usually kick off each episode with a little icebreaker, but I've taken to adding in as simple how are you? Since twenty twenty has been so crazy? And I think Adelaide is faring a bit better than we are here in Victoria. But how are you going over there?

Well? We are extraordinarily lucky here in South Australia. As you know, we've got very few cases and we're still wandering the streets pretty well, so I feel like I have no reason to complain at all looking what you guys are suffering through in Victoria.

Well, thankfully, getting totally engrossed in books and stories like yours has definitely been helping me through, which brings me back to the actual icebreaker, which is to ask what the most down to earth thing is about each guest.

And that's mainly because for people who have been in the media, and particularly yourself, after having read your book twice in the past couple of weeks, it can be so easy to put people on a pedestal and forget they're not superheroes, even though of course I still insist.

That you are.

And I've actually heard you refer to yourself a couple of times as a paunchy old man, so I'm sure there's something relatable that you can share in between all the superpowers.

Oh well, in addition to being a punchy middle aged man. If you could see me now, I'm in my tracking docks and my ug boots and i haven't shaved for three days because I've had the weekend off. So, yeah, I'm just a dag.

Amazing. I love it.

I love that you think you're a dag, mean while you're out actually saving the world. But that's really nice that you think that.

Well.

Yeah, So the first section is Your Wayta, which again focuses on humanizing our guests, tracing their story and pathway back through you know, all the chapters that came before the one we often encounter them in and I love to remind the listeners just how uniquely we all find our place in the world and how nonlinear the journey to get there often is. So take us back to young Harry. What was your childhood? Like doctor and nurse parents are really outdoorsy beginning to your life?

Yeah, I mean I think I had a very privileged childhood. As you said, my parents both had good jobs. My dad was a surgeon, so we were never short of money, we never had to do anything you know, tough really, so I consider myself to be incredibly lucky through just my birth and most circumstances. So life was, you know, as close to perfection as it could be. I think we're a very happy family, really close, very tight with our you know, uncles and aunties and cousins, you know,

big extended family, very Australian upbringing here in Adelaide. Life for me revolved around summer. You know, I would be pretty much in my short snow shirt, pair of thongs and walking, whether it was walking the streets or walking the beaches, getting sun burnt so badly every year that I would sort of count how good a summer it was by how many times my back peeled off, you know,

that sort of disgraceful upbringing that you would be. You know, the parents would be sent to prison for child abuse now if that happened.

But we've come a long way.

We have, and you know, I'm not saying this is a good thing, but that was that was summer for us. It was just stub toes and thongs and foot shorts and sunburn and growing up in a family who loved the ocean, small boats, catching whiting ie fish to eat, and also at the same time exploring the sea as a young boy as a snorkeler with a little hand spear trying to catch food and look at stuff. I just loved it, just look at stuff.

Yeah, And I think one of the things I loved so much about your story. The first time I heard it was that you can trace both your medical interests and your underwater interests back to those early days. Even though possibly no one could have guessed how that would manifest later, it was present right from those early days. And you've got your open water diving course at fifteen, so you'd started diving at least not in caves just yet, but you'd started the diving process.

Then what drove you towards that?

Well, it was an extension of the snorkeling and spearfishing for me, and in fact I started diving probably when I was about thirteen. We're lucky to have family friends who were into it. A couple of my parents' friends. One was a woman who was a marine biologist who was a really important figure in my childhood. In retrospect looking back, I used to go spearfishing, and I recount

one story in the book. I think that I came back from catching some reef fish which were completely inedible, and I laid them proudly on the beach in front of all the parents. I must have been twelve or thirteen at the time, and this lady came over to me and went, oh, OK, what have you caught here. And I said, well, I don't really know what their names are, but this is you know, I'm pretty proud of myself. And she said, well, you know, this one's are such and such, and this is what it eats

and that's where it lives. And of course you can't eat that one, it's not edible. And one by one she went through the fish and told me what they were, and told me about their habits and all this sort of stuff. And she then said, very cleverly, so what are you going to do with them now? And I suddenly felt this wave of shame over me that I just killed these really interesting and pretty fish for no reason whatsoever. And from that point on I kind of changed the way I looked at the water, and it

really made me think about what I was doing. So it didn't stop me spearfishing. I mean I loved I did enjoy it, and so, but I would only shoot a fish that I could eat. And I decided to learn the names and the habits of all these fish. In fact, she gave me a book. I've still got it.

The first book I had, called The Marine and Freshwater Fishes of South Australia, was produced by the South Australian Museum, and I had all these beautiful black and white plates of the fishes, pictures and names, and I just studied it. I became obsessed by it and decided then and there that I was going to be a marine biologist, which a dream that I really hung onto actually, And it was almost a toss of the coin choice between that, veterinary science and medicine for me, which of the three

I would do. And I ended up in medicine, partly because I got the marks to do it, and I missed out on vet science. Interestingly, I had enough marks to be a doctor, but not to be a vet and a cousin who was doing marine biology told me that there were no jobs in the field and taught me out of it. So it was and still is quite a strong interest for me.

It's so interesting looking back now and realizing how just how early that was in your journey, and how much more control you have over your decisions later in life than you think. I imagine at that time, when you were choosing between those three things, you thought it was like a forever choice and it was the most important decision you were ever going to make. But I think we so overestimate how final that decision is and how many different directions your life is expected to go after that.

And you know, medicine didn't put an end to your marine adventures at all.

No, definitely not, although I do I worry about some doctors because they do become completely immersed in the world of medicine and their career. It's almost like a vocation for them, and many of them find themselves at retirement age.

And I'm starting to see, you know, some colleagues who are maybe ten years older than me, they're getting close to retirement, and some of them have said to me, Ah, I sort of admire the way you've conducted your life, Harry, you know, or other outside interests, because I'm suddenly thinking I don't know what I'm going to do with myself. I've got nothing else. And you need doctors to be pretty focused, obviously on their job, and you'd want that

in your doctor as a patient. But I also think it's very important that your doctor has a life outside of medicine, because how can they relate to people normally. I mean, some doctors don't really have to if they're looking at your X rays or looking at a piece of view under the microscope. But you know, if you want your GP to be a well rounded person, so they have some idea of what goes on outside their office.

It's so interesting that you said that, because this is where I get so fascinated. So I think the people

who tend to be not necessarily the most successful. And the whole idea of this podcast is to separate and make a distinction between success and fulfillment, because I think we chase success, we get on this very productivity hamster wheel and end up on this autopilot's circuit that can lead people to be in their fifties and sixties and retirement age and have no hobbies and no interests and no experience and think what have I done this time?

But the people who have sort of recalibrated from financial metrics and titles and looked for joy and had activities, I call them your playt eight. Like if you don't play outside your vocation, you're missing a whole part of yourself that's for joy and exploration and that develops other sides of you that actually makes you a better worker as well, because you've got a.

Breadth of experience behind you.

And I love that You've always had such a strong endeavor outside of career that some would think would be all consuming, but you've still managed to do both, and I think it's obviously made you better for it and made your life experience better for it.

Yeah, and look, I mean it depends how you measure success, for example, in medicine or in any career. But you know, obviously there are anythetus out there who are far more academic, They've done more research, they might be professors, they might be far more skilled even at giving an anesthetic. But I certainly feel that I do enough and have been well rounded enough to give a good quality anesthetic, a safe anesthetic. I'm not saying I'm the best, but I

don't think i'm the worst. Fortunately, it's not a bad place to be. No. No, So I don't think I'm a star of Anesesia by any stretch. But my career has been so interesting to me, at least because I haven't been happy just to give anesthetics nine to five. I've really mixed it up in terms of the places I've worked, the types of medical work that I've done, which include stuff aligned with but not purely anesesia. The whole time, so that's been really important to me as well.

I find I get this sort of five year each with my work. Where I go, I think I need to shake things up a bit and try something a bit different. I always do some anesesia, but the other half the time or part of the time, I might be off doing diving medicine, or eero medical retrieval work, or working in a third world country, or just something different. And as long as it fits in with the family, which it usually does, you know, it's been a huge success for me.

And that's the other thing that you just touched on that's important, is that it only has to really work for you. We're all meant to have different interpretations of a successful and joyful and fulfilling career, and for some that is pure academic achievement and rigor, and for others that does involve more of a balance.

And I love that.

I love finding people who have stuck to things that have really invigorated them their whole lives and not let go of it because society thinks that things should look a certain way, or career paths should look a certain way.

I certainly don't want to disrespect those medical people who are so focused and so passionate about their work that that is their life. I mean, that's fantastic, but that's never been me. I can't be happy unless I've got some way of making life a bit messy along the way.

Well, your life has definitely not been short of a challenge in terms of all of your vocations. So before we get to obviously the chapter that I am so so excited to talk to you more about, how did you actually start that kind of broad practice.

So firstly, it takes a really.

Long time to specialize, as in anything including anesthesia, and then on top of that to branch out after your specialization to get experience in aeromedical work. You ended up in New Zealand, and then you were here and then rural communities and then even started to sort of move your way back towards diving in hyperbaric medicine back in Adelaide.

How did you craft that?

Do you have that level of control from early or did you set out from the beginning, like how did you build that career for yourself?

A lot of it's a bit I kind of go with the flow sometimes, but it comes back to this getting bored easily probably if I'm doing the same thing for too long, I start to seek out other opportunities.

So diving in hyperbaric medicine was an obvious one because of my interest in diving since such a young age, and a lot of hyperbaric medicine units in the public hospitals in Australia are run by an esthetus or intensive care doctors or emergency medicine people or occupational physicians tend to be the group, but anissaus primarily, so I was always surrounded by people who worked in that field and it was always in the back of my mind that

that's something I'd like to do. And yeah, an opportunity came up, basically, so I started to do that and working part time, and I was just starting to think about maybe I've done this for long enough. I'd been working there about twelve years part time, and I actually opened the health Essay Health computer to renew my application or whatever it was, and the advertisement popped up for MedStar,

Theessa Ambulance eramedical Service recruiting. Now I went, oh, that's me, And that had been the other thing that I'd just been thinking about because I did a bit of it when I was training as an anissa, certainly in Adelaide and New Zealand. I did some so that had been in the back of my mind is something I'd like to revisit. And so this message popped up on the computer. I said, wow, I could just give them a call.

I suppose see what happens. And I knew the guy who was the director of the service, and so I just gave him a ring and said, look, I haven't done this for the last eight years or something, since I was a trainee or a bit longer. Perhaps is it worth me coming down for a chat? And he said, sure, Harry, come down, We'll have a talk. And there it was. So I got into that and really threw myself into that. Then I found it to be really to my liking. I love the excitement of that work, and I love

the organization and the people that work. They're amazing bunch of doctors, nurses and paramedics, all really extraordinary people. And yeah, it got right into it and was going well until this crazy thing in Thailand happened when I had to sadly sort of step away from it because I just didn't have time to commit to it.

Yeah, I still actually looking at your LinkedIn and the.

Timeline, I was like, how has he fitted in all this stuff? Oh my god, how are you not a hundred?

It's just I think you're such a testament to the fact that you can fit in a lot of life experience. If you're good at time management and you're committed to if you genuinely love it, you can make room for the things that you love.

Well. My wife does take note that if ever things are a bit quiet, diary is looking a bit empty, then I will find a project to sabotage that status quo very quickly, and I usually end up regretting it, going, oh my god, I've got so much on my plate, and I get really stressed. But then she says, she notes that, well, as soon as you're quiet, then you know you do it to yourself. You find something to take one.

Sucker for punishment.

Yeah, but I also think people who have an insatiable thirst for adventure and extension, like self extension and mind

opening and new experiences your comfort zone. I have stepped out of it once, obviously, leaving corporate and moving into business, and I sort of patter myself on the back for five years, thinking like I'm never going to have to take another step out of my comfort zone, but it catches up with you over time you grow into becoming comfortable again, and you need to continue to seek out those next steps that challenge you. And I'm sure you probably didn't imagine that the thail end step would be.

I mean, that's a huge jump in challenge from a difficult thing to something that the globe thinks is impossible quickly. Just before we go there, I mentioned before we started recording that I'm also a sucker for a niche community and just digging really deep into things that day to day most people have no idea about. But when you start to dig beneath the surface, it's there's a whole

worldwide community of people who are fascinated by something. And I didn't actually think about cave diving as being such a specific skill, like separate to just deep sea diving or open water diving.

It's very very specific.

You all seem to know each other, and it's very technical. Like when we're talking caves, it's like at any one time, you can't just surface like you're usually in tunnels. And I didn't know any ofone would dive into zero visibility, and how do you actually become proficient at that, Like, how do you graduate from like a normal diver to a cave diver.

How do you even find the caves?

All these days? It's a very established pathway actually, So if you're a comfortable scuba diver and you're looking to do something more challenging, then I guess that's the one of the next logical steps. So there's an area of scuba diving that's become known as technical dive, which is

basically going beyond the normal recreational dive limits. So, as an open water scuba divy, you're told that really the maximum depth you should ever go to breathing a tank of air is forty meters, maybe even thirty is recommended, and you have a single tank on your back, you've got two regulators coming off that, and you always dive with your dive buddy right next to you. That's the

sort of mantra don't hold your breath and ascend slowly. Well, when you go technical diving, you're looking to extend those limits, whether it's in depth or duration or into what we call the overhead environment, which might mean inside a shipwreck or inside a cave or with an artificial ceiling above you, which is a decompression ceiling, which means that you can no longer go straight to the surface because you've got to do stops on the way up, otherwise you get

this decompression sickness or the bends, and to do that it requires a lot more training, It requires a lot more time in the water, and it requires specialty equipment and sometimes other gases that you breathe on as well.

And cave diving, you can train for cave diving the same way as you can train for some of these other aspects of technical diving, and a lot of cave divers sort of gather all these certificates along the way, so they become proficient in deeper diving with mixed gases, and they might start using rebreathers, which are a different

type of diving equipment. They certainly have to learn to use more than one scuba tank to prolong both their duration but also their redundancy, because if you're obviously in a cave and you can't go straight back to the surface, if one of your pieces of equipment fails, you have to have a backup, and you need to back up for everything including your lights and your tanks, in your

ear supply and so forth. So in Australia, the easiest way to learn all this is through the Cave Divers Association of Australia, and they've got three or four levels of training. I say three or four because I should know, but it keeps changing, so I think at the moment of three, yeah, And it takes maybe four to six years probably to go through that training progression quite slow and arduous, and you need a lot of time underwater

in between each of the levels of the courses. And because there's so much attention to detail and safety, the sport is actually incredibly safe and the risk of a bad accident, which means a death really in this sport is very very low.

Indeed, Oh my gosh, I just sort of shiver thinking about the idea of having a roof over you so you can't just sort of float up to the surface if anything happens. And I read quite a few times in the book you're mentioning that, you know, keeping your cool and not panicking in those situations because you can't just sort of rip off your mask and fly to the surface is something that also with your training technically comes a lot of psychological training to get yourselves ready

for the situations that you're going too. What mentally keeps you going through say a zero visibility you know, tunnel that your top and your bottom at both scratching, Like, to me, that's just so scary and foreign. What makes you keep going? Is it the view that you're going to get at the end. Is it the things that you've seen at the end of some tunnels that makes you go? Or the fact that no other humans been there? Is it the adrenaline or the risk? Like what brings you back every time?

Yeah? I guess it's the motivation. Depends on the motivation for what you're trying to achieve. You might be in there for reasons of exploration, or you might be in there because you're doing some work for some scientists, or you might be in that situation of a restricted zero visibility squeeze as we call them, because you've got to go out that way to get home and that way, you're pretty motivated. I can tell you to stay calm. The way we cope with it is purely through familiarity

and training and pattern recognition and muscle memory. It's just having done this sort of stuff time and time and time again, in gradually increasing difficulty circumstances. And that starts right at the very beginning with the training. You don't actually get to see very much at all during cave diving courses because you've either got a blindfold on or someone's ripped your mask off face. So, yeah, the courses, I mean, the courses are run not in those sort

of environments. They're running open water sinkholes where you can just pop up to the surface. But mentally, I tell you, you're in a cave when someone puts this blindfold on you and then taps you on the shoulder, which means something bad's about to happen to you, and they pull your regulator out of your mouth or or you know, cut the line that you're following to get out of the cave. All this sort of stuff. Then you have to fall back on the training that you've been given

and solve the problem. And if you don't solve the problem, you don't pass. And they give you a thing called a stress test at the end of the course, which sort of throws all these things together in quick succession. And I think some people, I mean most people pass these things because they're you know, you're pretty comfortable underwater

by the time you start this sort of course. But some people actually go, you know what, this is not for me because I don't like the way I'm feeling, or I don't like the way this makes me feel. So maybe cave diving is not for me. But for most people who obviously who pass the courses, they get a lot of pleasure out of that environment. Yeah, and actually the more advanced you get, the more gnarly some of these places are. They can actually be quite fun.

It's like sort of three dimensional problem solving with your eyes closed and the clock tickings. It's kind of weird, but it's fun.

I often say that self awareness is the best tool you could possibly develop because it allows you to really find what you think is fun and block out what anyone else might think, because I'm not sure we would all agree that what you're describing is our idea of fun. But I guess it only really matters that you think it's fun. But as we know now, you've been called up on a global government level to use your skills outside of just pure leisure. Was Thailand the first time

that happened? Or can you even dive professionally. Had you ever done rescue missions before?

When you say professional, I guess the answers no, because never been paid for anything. But I am involved in volunteer cave rescue in Australia and in about the year twenty ten I actually started a training course for this sort of scenario because I recognized that there was a lack of a capability not only in Australia but worldwide for rescuing people through an underwater underground body of water.

And you'd think, well, why would you ever need to do that, But you know, as cave divers and cavers, we often go to remote caves which we have to visit by passing through a sump, a water filled section of the cave. For example, out on the nullaboard plane, there's a very well known cave called Cocklebitty Cave and it's about six kilometers long and most of it is underwater, but it's interrupted by two rock chambers a third and

two thirds along the way. So to cross these rock chambers you have to get out of the water and carry all your diving equipment across this underwater mountain pretty much and then back into the water and then head off again to the next one, and then at four and a half kilometers in there, you come across the second one, which is even bigger and longer, and again

have to carry all your equipment across it. And these places like a huge rock pile, their massive boulders about forty meters high that you have to climb up and across the top and then down the other side into the water. So I was out there with Craig, actually Craig Challon, and I said, I remember saying to him, what happens if one of us falls over here and breaks your leg? Or how would anyone possibly rescue us?

Because the only way out is back through the water, back across the other mountain, and then back through the water to the entrance. That seems like an impossible quest. So it was kind of selfish self interest that made me think, well, we need to we need to get organized,

because I don't think anyone could rescue us. So I went home and we gathered some of the emergency services around, the police divers and some very experienced cave divers and so forth, and we ran this little weekend of chit chat and exercises, scenarios and came away with a kind of a coarse structure which I've subsequently taught every year since in South Australia, but also taken it over to

New South Wales and New Zealand. So we'd spend a fair bit of time by the Thaire Cave Rescue thinking about how we were going to approach this sort of problem. But we never anticipated they would be non English speaking children at thirteen of them, and in such a difficult cave, and people who were not cave divers. I mean, they were quite good cavers, the fact that they've gotten themselves that far in, but they certainly weren't divers.

Well, Okay, so I'm so excited about this part of the interview. And I've already read the book, so I already know a lot of the detail. But what's so interesting to me is that it was all over the news. Of course, we all knew the fundamental details of the thirteen boys getting stuck inside the cave, water coming down, they couldn't get back out, and you know, you mentioned the whole situation of there was actually no way out, accept a way that they couldn't physically get them, And

then we all knew that the world came together. There was a lot of difficult to get in them out, but then they got out, and I think a lot of us missed a lot of the subtleties in between of actually how literally small the chances were of a successful removal of the children from that cave were.

And as I was reading it was just particularly because.

It was written by you, guys, and written in your chronological mindset at each stage of the plan, where you you know, the plan you ended up with is definitely not the one that you guys first started with. Just talk us through it all from your perspective. How did you get there? I know, you guys, you know the Thai navy seals had had a good go before you even arrived, before you were called on, and then there was a lot of diplomacy to get there. But there

were nine chambers, you know. I think we all thought that this cave diving again, misunderstood that it was just some boys in a cave. But there were like nine different chambers to get in, and you're in your wet suits and you're dragging all your stuff, and even just to get in to find them was a challenge, let alone, to then work out how to bring out thirteen of them who couldn't dive themselves.

So take us through it.

Well, you've painted a pretty good picture. Actually, I don't know if I could do much better, but yeah, so, I mean, there were a couple of interesting things about this cave that made it different to what we would consider normally going into ourselves. I would never go into a cave that is actively flooding, that's the first thing. So the environment itself was potentially quite hazardous. In fact, when the first rescuers got on site, they tried to

dive in. When once they got some divers there, like the Thai navy guys, they tried to dive in there. It was physically impossible to swim into the flow of water appearing from the entrance of the cave. So then they called these British guys Rick Stanton and John Valanthine because of some local contacts a guy called vern Unsworth, a British caver who lived in the area. Rick and John are extremely proficient, like they are the go to

guys for this sort of thing. There are two of three or four people in the world who have even swum an injured person out through a cave underwater like this before, so they had the experience the runs on the board, I guess, and also Rick and John in particular, they're kind of the rock stars of our sport, if you like. They are very very highly regarded, very tough guys, very capable.

Second only to you and Craig.

Now obviously, well i'd say I would honestly say, we're very very long second to these guys. They're just in a class of their own, honestly, and I've been on expeditions with them, so I can tell your first hand that they know they continue to do stuff that I'm just in awe of, just way out of my leg But anyway, so they arrived on scene and they thought, well, we'll give this a go. They tried to get into the cave and they were the same They got spat out by the strength of the water. So they were

pretty despondent. They thought, there's no way that anyone's getting in there to get these kids, even if they are still alive, and the chances are frankly that they've already drowned.

But they stuck around for a few days. They kept trying, and the reins eased off, and gradually the water settled to the point where they could actually start to make some forward progress, and in what I would say is the greatest diving achievement of the modern era from what I've seen, they drag these huge sacks full of climbing rope with them and laid this rope through the cave to where the kids were over the next three to four five days, and that would be extremely difficult and

dangerous dive to do. You can imagine the water is like coffee. You cannot see your hand in front of your face. You're just pushing and swimming, pulling yourself hand over hand, pointing yourself into where the strongest flow is coming from. You have no idea where you're going. There's so many places in a cave like that that you can get trapped or hooked behind a rock in the flow,

or squashed or whatever. And they would tie off the rope every fifty meters or so, so they always had this rope they could follow back out find their way home, and every now and again they'd pop up into an air chamber, from which point they could walk or wade or swim on the surface to the next point where they had to go back underwater. And as you say that, repeated nine times and a very very long way, about two point four kilometers in the end, so it's a

hell of a journey. And then finally popping up into Chamber nine, whereby they took their masts off and sniffed the air to see if they could smell any sign of where if the kids were in there. And Rick I remember him telling me that when he first smelt the air in that chamber, he thought he'd swum into a tomb, because he said the smell was so bad that he was expecting to find the bodies of these

kids floating in the water. So, you know, huge pressure on these guys, and that must have been just horrific swimming through that water waiting to find all these bodies. When suddenly these lights came on up the hill up to the right, and one by one, all these boys started running down the hill. And you've probably seen that amazing bit of video from John Valanthin's head camera when he says how many of you are there, and one of the boys, Adul, who speaks a little bit of English,

says thirt. John says, brilliant, you're all here. Rick, being a bit of a wise guy says he'd already counted them by then he knew there was so that's pretty cool. And of course the whole world suddenly went, yeah, they're saved, you know, no worries. But anyone who knows anything about caving and cave diving went, oh my god, what do we doing now?

Well, I think that's exactly That's it, the fact that none of us did know anything about caving and cave diving. As soon as we knew they'd been located, we were like, it's done, Like you can just sort.

Of helicopter them out somehow, like drill a hole in the you know.

And as I read the book and I realized just how that almost posed a worse problem for the caving community and the emergency services, because if there's a dive that Navy seals can't do, like who is going to do it? I don't think anyone at that time in the general public actually understood how technical the problem became, and then how impossible it almost was. That if men could barely dive in to find the boys, than how to even get them out. And I know there was

an attempt to drill. There were some attempts to drain the water out the entrance.

Elon Musk then.

Got involved with the submarine thing and the tube that he was going to try and put through, And I remember, like I've obviously voraciously consumed content on this whole thing since reading your book, because I've been so fascinated looking at some of the diagrams to scale of the tunnels between each chamber. It's just mind boggling to think that they got that far in and that you guys then had to get every time you went in and out was hours, not like twenty minutes or half an hour, but hours.

Yeah, it was about a three hour trip each way, which got a little bit faster actually as we got more practiced in the cave and coming out was slightly faster because you were going with the flow, I suppose. But yeah, it was a solid day in the cave. We're in there for ten or twelve hours each day, you know, getting to the kids, looking after them, and then coming back out again. Oh my gosh.

And so very very few of us, I mean, many of us have found our purpose and maybe done something quite rewarding with it, but very very few of us have actually been called up as the only person in the universe who is capable of doing a certain task, especially not by a government after the Seals have already not been able to do that.

So what did that feel like for you?

Well, I was excited, to be honest, because we've done all this training. I've been you know, the last eight years or so, I've been running these courses thinking, actually,

we're training for something that will probably never happen. And I know Craig and I were secretly hoping that we would get called over to Thailand because you felt like a fireman who's never put out a fire, you know, you want to get a gold And it's funny, I've spoken to quite a few soldiers, especially special forces, people who are desperately keen to actually test what they've learned and their training and just and themselves, I suppose, which

is hard to understand and maybe even harder to sympathize with, but I sort of understand it. Now, You've got these skills and you really wonder whether you're up to the task yourself, and you want to put them to some good. So yeah, we were keen to go and to say I'm the only person in the world who could have done that. It's a slight exaggeration. There are definitely other cave diving anesthetis, but maybe no one else is silly

enough to get involved. But I just happened to know Rick Stanton and some of the other people that were already there, So yeah, I was always in the crosshairs, I suppose.

I mean, even still having said that, though, I feel like there's still maybe only five or you could count them on two.

It's just not one hand.

Yeah, And that's why.

This fascinates me so much, because that very very unique intersection between you love the cave diving and your actual day job. What a sliding doors moment that that suddenly became so relevant for a whole global community and like

thirteen families. It's just absolutely incredible. And I love how you and Craig were actually really honest about from the very beginning, how you were kind of angling to figure out how you could get over there, because you did, we actually have skills that were relevant to offer to a very very difficult problem once you actually got there, and then I mean, everyone who's interested you can read in the book there's a lot about even just diplomatically,

how you get someone there, and then you get them immunity when they're going to go into something so intense and high risk. Can you describe the actual tunnel to us and like what you actually faced, because again I don't think any of us really understood at the time that it was hours in, hours out. The only way really that was left after exploring all the options was to sedate the children, and then it was on your shoulders to choose with what how long would that last?

Would they panic if they woke up? You're sedating them, so who's diving them out? All the other divers had never injected anyone with anything before, Like my mind, just none of us in the public heard really because it was just so technical. But like, how did you and Crag go about making some order in the chaos?

Yeah, there were about a million decision points to face, and we had a very limited time to get through that. The forecasters were saying that we probably had three to six days before the monsoon rains would really kick in again. And we knew from the experience of the first divers on scene that once that happened, and if the monsoon came and stayed, then that's it. That's the end of

the rescue. Because the river floods again, no diving can be achieved, and if we can't drill a hole or something else, then those kids to have to stay there until the end of the monsoon, which is conservatively three to four months, probably more like five by the time all the water drains away again. And that turned out to be the reality of that, by the way, so we really had twenty four hours to make a decision

how we were going to do this. As soon as I arrived, there was an assumption and actually quite a lot of pressure on me to agree to this anesthetic plan. And I had said to Rick on the phone before I even left Adelaide, that I think that's impossible. It cannot be done. It's never been tried. I can think of a million ways those children will die if we

try and do that. But I'm prepared to come over and maybe as a doctor, I can go and look after the kids while you guys come up with a better plan, or as a cave diver, and maybe I can just give you guys a hand in the rescue or even in the recovery of the bodies, if that's what's needed, because the kids still had to come out

one way or the other back to their families. So on that basis, we went over and as I say, as soon as we hit the ground, everyone's going, right, well, how are you going to anesetize and what are you going to do? I'm not doing it. I'm not even talking about it until I've looked at what else is

going on, until I've seen the cave for myself. And of course I'd been racking my brains for the last twenty four hours anyway, thinking about how I would anesthetize them, and getting as many opinions from friends and colleagues about that in the meantime, so I had a bit of an idea what I was going to do if it came to that, But for me, that was off the table until it was absolutely the last resort. And you've mentioned all the plans around water pumping and draining the

cave and drilling and all these sorts of things. I had to be sure my own mind that none of those things were possible. I had to be sure that it wasn't possible to teach the kids how to know just the rudimentary diving skills we could safely escort them out awake. I had to be sure that we couldn't maybe just stock up the larder with food in there for them and let them sit there for three months,

if that was the safer option. And so my first request or demand really was that I had to dive the cave myself and have a look at it and see the kids for myself, see the environment they were in, see how difficult the cave was, and that would just

help me get my head around all this stuff. And that's all I had to do, really, to be very sure in my own mind that there was no way these kids were coming out any other way than anesthetized, and that they would not survive more than a few weeks in there without food and proper medical care and so forth. And not only that, but there were four Thay Navy military people in there with the kids, and

they were in exactly the same boat. If the kids were not rescued, that meant those four men would also perish in there. So it was a bit of responsibility to do something. And I actually still believed, really right until the last child was out, that this would not work, and I believed it with all my heart. To be honest, I'd still thought there's no chance that this plan can conceivably be successful, and that any of these kids could survive,

let alone all of them. And the only reason I managed to push your head with the plan was that the alternative seemed even worse to me, and that was to leave these kids to die very slow and lingering death. And I couldn't walk away from them with that, you know, on the card. So we had to try it. And I thought that, well, at least if the kids die under our care, they'll be anesthetized and asleep when it happens. So when you put it in those sort of binary terms,

it seemed like a pretty clear choice. You know, it was a bad outcome for me if we went with that plan, but either way, the kids would be dead, and we forget that.

You know, I think the images that you get in your mind are of them with light and heat and dry flaws.

But when I was reading through the fact.

That they like to get food in someone actually has to dive it in that three hour trek, like there's no convenient way to actually get stuff to them and goods to them. Like there's just so many things that I just couldn't unless you've read the book. And I highly recommend everyone does, because showing how you eliminated each option was actually fascinating to read how technical then the

ultimate solution did become. And also I'm so fascinated by self doubt and how psychologically how much of a barrier that can be to us in our day to day lives, but let alone in a situation where the outcome that you're doubting is actually fatal for people, you know, children. I just don't know how you stayed focused for such a huge task with so much weight on your shoulders.

And I've heard you speak about how what you actually had to do with the children to test their masks and stuff that is, by any normal standards in any normal situation, counterintuitive to anything that you would do for someone's well being, But it's what you had to do. So talk us through the sort of mental challenge you went through in coming to that plan and then actually executing it, not knowing each day that any of them had survived until you got out at the end of

the day. Like if anyone doesn't know, doctor Harris was in Chamber nine with the children all day and the other divers were diving the children out sedated. So do you want to maybe explain that process as well, so that people know how it happened with the other divers sort of taking one child.

There are some really interesting moral dilemmas in this whole story which I've become a bit fascinated with actually, and how we you know, again sliding door moments. You know, if things had gone differently, we would have faced some really awful moral outcomes, I think. But anyway, the actual process of anesthetizing these children was that I would go to Chamber nine with the four British divers who were going to actually physically swim the children out. They would

take charge of one child each. I would call each child down one at a time. They would already be dressed in a wetsuit. They'd come down and sit on

my lap in the water. Was at the base of a very steep slope, so I was in water up to my lower chest, I guess, and I couldn't really get much higher out of the water than that, So I'd cock a knee up and they would sit on my knee with their top half of their body up out of the water, and I would show them the needle and syringe and I would then inject them in the leg with ketamine, the anesthetic drug, and it would take about five minutes for that to work, and they'd

slowly get a bit knotty and then get limp and become like a rag doll and fall asleep, and so I'd support their head and their face to make sure their airway was okay whilst that happened, and then the British diver would bring over the full face masks that we were going to use to make sure that their face and airway stayed dry during the diving extraction, and then we'd try and put that on the kid's head, which is actually quite hard to do when the kids

will floppy like a rag doll. So we had a few issues with that, and a couple of kids sort of ended up flopping into the water by accident. And you know, it's not even funny, but it is, well, that kind of is, but it wasn't you know, I agree entirely. I mean, it was just a circus and we were sort of giggling at times because it was just so awful and it just seems so hopeless. It's like a movie of how not to give an anesthetic basically.

But anyway, with us. So we get the mask on, and we do the straps up so tight because we're terrified that these masks would get dislodged or bumped with all the stalic tights and projections in the cave, and the poor kids ended up with squashed noses and I think some blood noses and things. But anyway, they were safe, obviously. And then once the mask was on, then I would

do this first test. And I remember very clearly with the first boy that we did this too, getting him and just pushing his face down into the water for just a few seconds, and then lifting him up again and expecting the mask to be half full of water and seeing that, okay, it's still dry, and so try again for maybe twenty seconds, and then finally leaving him lying face down in the water. And I remember very clearly the feeling of this is not what I'm supposed

to be doing as a doctor. You know, I feel like I'm basically ethanazing this child. It's like drowning a kitten or something. It just felt it felt awful and

so so wrong. But the kid be bubbling away happily, you know, the bubbles coming out of the face mask as they should and so the British dive would then go off and get his own equipment ready, and whilst he was doing that, I'd get the kid make the final preparations by tying the kid's hands behind their back with a carabine a clipped to two cable ties, and

then wrapping their feet together with a bungee cord. And the idea of that is to make them into the most streamlined kind of dart that we could, so they'd be easy to push through the water and through these tight restrictions in the cave. Because if their arms were flailing about then obviously they would get injured or tangled

in the ropes or the projections in the cave. But more importantly, if they suddenly woke up underwater water, then they might reach up and rip their mask off, or even more worryingly, do the same to the rescue diver and drown the rescue diver. Because you can imagine if you're in the tight confines of a very restricted part of the tunnel, you can't see anything at all, and suddenly this kid starts waking up and thrashing around, you're

both going to end up dying. There's no way that one of these British guys was going to just abandon a child. You know, they would do everything in their power to try and rescue them, and that would almost certainly end in the death of both of them. So, you know, the first rule of any rescuers to protect the rescuers number one, and then the victims come a close second, but it has to be in that order, because without the rescuers, you can't do anything for the other boys. Yeah.

Absolutely, What were the in the sort of Gnarlia Settler that you caught it nally before the narliest section of the dive?

Like how tight are we talking? And how rough?

Like I think we have this idea of like a tube that's smooth, but I'm sure it actually wasn't like.

That at all. Yeah, the type parts of the cave were different configurations. Most of them were quite wide but very flat, so maybe I don't know, you know, this sort of height you could fit your head its head and chest through it and then you would be scraping with your back and your chest and you would have to wriggle, you know, to push yourself through them. So

they were pretty tight. Like if I was any bigger, I would struggle Fortunately the floor of the cave was mud, so that actually works in your favor because you can scrape a bit of a trench through, and the more times people go through, the easier it gets.

So you'd have to push the child through first, or you'd go through and then pull them.

Yeah, or maybe have them alongside you. But sometimes there was only one spot in that wide what we call a flattener, only one spot where you could fit through, and the rope wouldn't necessarily follow that part of the cave, of course, so the rope might be out of arm's length, and then you'd have to feel out with your other

arm to find where that hole is. And as I say, it's like a blind three dimensional problem solving exercise, which is fine when you're by yourself and you've got time on your side, but when you've got someone else to worry about, and knowing that the anesthetic will be wearing off and you've got to keep moving, the kids getting colder every minute they're in there. There's a lot of pressure on these British guys to do this, and a huge amount of mental strain and stress on them.

Yeah, absolutely, And they had to inject the kids a couple of times to make it last, didn't they? Because the extraction was so long, the sedatives wouldn't actually last long enough, would they.

Yeah, Well, ketamine is a drug that we use quite a lot in ana seesure and especially in emergency situations because it's very forgiving in many ways. But giving it as an intramuscular injection is a bit unusual, not unheard of, but a bit unusual. But giving it repeated doses as an intramuscular injection is just about unheard of. And so I had no idea really how much to give, how

often it would need to be given. There's really no recipe for what we did, so I just had to best guess it, really, and just as best we could as we went along. Now, of course, these other divers aren't medical people, and so they took on an enormous responsibility. I mean, they never would have looked after an unconscious person on the surface, let alone underwater when you can't

see the patient. So, you know, imagine if I asked you to do this right now in a you know, if I turn the lights out and said, right, there's an unconscious person there, just look after them for three hours, keep them alive and if they start to wriggle, inject them in the leg. They'll give you one little torch. It can shine on them briefly while you do the injection.

Let alone, if we were in a tunnel.

It was a big ask on these British guys, which says a lot about the quality of these blokes, which is why I was alluding to their excellent natures early on.

You know, one thing I did love about reading the book was how much of you guys and the other personalities you injected into the story as well. Like it was, it's a terrible, overwhelming, all consuming experience, but you have to be able to laugh at the end of the day, like you guys have to be there to make each other sane through If a child like you know, slips and slides on their wetsuit down into the water, like you have to laugh because what else can you do.

And I love that you all had banter with each other and we're each other.

A hard time. That's very much. That's very much for our benefit, that kind of black humor, I think, to keep the positivity to keep going back another day and another day after that. You know, you had to jolly yourself up a bit with some kind of technique.

Yeah.

And why I love going through these kind of events is that in hindsight, of course it all worked out.

We know that there was a happy ending, but you didn't know that at the time. Like each day when you came out, yes, you got one day closer, but there was another whole twelve to fifteen hours twice and then another time for you to get through. So when you first came out and realized it had worked for four of them, did you have any time to think or celebrate that before you were like back the next day or no?

Not really. We had to go straight into debriefing meetings as soon as we got out of the cave after that first rescue day, And obviously we found out the first four boys had survived, which was great news. But actually that night I was more frightened, I think than

any other time during the rescue. I sort of got it into my head that I don't know how we got away with day one, but tomorrow this is definitely going to all come unraveled, and we're going to be found out to be the fraudsters that I know we are. You know, I just was so convinced this plan couldn't work. And so that night, you know, I virtually had no sleep. It was raining all night, so I was listening to the rain on the roof of the hotel, thinking we might not even be getting back in to see that

boys again. And you know, that was really tough each day saying goodbye to the remaining boys and those military guys, thinking if it rains tonight, you guys are dead. We're going back to our hotel. We might never see you again. I felt very guilty leaving each day, I have to say, and I.

Can't imagine the exhaustion you would have had as well, just with the moral and ethical and physical questions that are going through your head the whole entire time. But also I think we trauma is kind of not easy to deal with, of course, but if you can rip a band aid, there's something to that. Whereas you guys had to just sit there for fifteen hours and wait, there was no just push the boy through the tubernis out the other side. It was such a long process of you waiting with no answers.

And yeah, I found the swim out of the cave each day quite a good opportunity to kind of try and relax and just say, okay, well, look I'm in a cave, I'm diving. This is what I enjoyed doing. I'll just follow this rope out And that wasn't technically too terrible for us, and going with the flow of the water was actually quite relaxing. So I found those swims out with my own thoughts, because there's no point

diving with anyone else in those conditions. They just get in your way, so you're completely by yourself for those few hours swimming out, and I found that actually quite relaxing strangely, and helped me like a deep yeah, get some mental energy back, thinking about okay, what do we do? What could we do better? I wonder if any of them are alive, but we'll soon find out, I suppose.

So. One of the things that stood out so much as well is just the rellis of those young boys, like they were so young, some of them, but every time you would come out of the water, my heart would just smile reading about how they would greet you with such happy, positive and optimistic smiles. And the coach was so careful to look after their well being. And then the Navy Seals agreed to just sit with them until you know, they weren't leaving until the boys left.

What were some of your biggest.

Takeaways on sort of humanity and the fact that the global community can come together to pull something like this off. I imagine it kind of changed your life in how you see life and people and connection and community.

Yeah, you've summed it up just there. I mean to arrive on this scene with people from every country you can imagine being represented in some form, whether it's their military or some volunteers, or some equipment being there on site that's been donated or sent over. Plus the thousands and thousands of tied people on site, from people cooking food for all the volunteers were handing out clothing or rubber boots or hats or umbrellas or you name it.

You could get a free haircut there outside the cave entrance if you had the time. Unfortunately, there's some beautiful typhood being cooked there and these huge woks, but we didn't have time to even see any of that. It was like a sideshow ali at the agricultural shows. It's just people with all these stools and you know, this sort of happy atmosphere it was an amazing place. I only got stall. It was like that. It was I only got to very briefly walk around at once and

just to see what was going on. But it was so colorful and vibrant, you know. But yeah, and then it was back into the meetings or planning or you know, sorting out equipment and stuff. But it was kind of a cool atmosphere there, and overwhelmingly this feeling of community that all these people were there for one reason, one reason only. It was extraordinary thing to be a part of. Actually, it was a real privilege.

I love that you guys have maintained your connection with the boys as well, and that you went back to Thailand to see quite a few of them.

I think I think we saw eight of them, including the coach, and that was amazing obviously to see how they're doing and to meet some of their parents, because we never even saw the parents while we were over there the first time, which brings me to one of those moral dilemmas, you know, about informed consent, both for the boys and for their parents. And I'm kind of glad I never got to talk to the parents beforehand, because what possible way could I frame that conversation with them.

You know, here's a plan. I think it's got one hundred percent failure rate. But we're but but it seems better than leaving them to die of illness, starvation, or exposure. What do you want me to do? I mean, how could you ask a parent to make that decision? It's impossible, I think.

But I love that you asked the boys, though.

Well, we told them what the plan was. I don't know whether we were really seeking their permission. But having said that, you know, the last thing I would have wanted to do, in fact, I don't think I could have done, would be to drag a child, kicking and screaming, to the water's edge, plunge a needle into him, and then basically a soul him in that way. I couldn't have done that, So I had to give them sufficient confidence such that they would comply. I guess for my

own sake. I mean, I couldn't. You couldn't do that to a child if they were resisting. It was hard enough to do it with someone who was being nice to you.

Yeah, but it seemed like they all had really lovely memories of your anethetist banter and just sort of slowly, you know, going off into another world. How you guys talk to kind of fill the space and make them feel really comfortable. I was reading that some of the boys when you asked what they remember, they were like, doctor, brigard, job job job, job, job, job.

That's cute.

Yeah, they tease. They did tease me a bit when we finally met up with them that, oh hello, hello, olch you know.

Job job next.

Did you have much dead time while you were waiting between sending the boys off or you were just sitting in the cave waiting.

I tried to send them out at about forty five minute intervals because we had to give the dive downstream in the other chambers time to process them and send them on their way and red anesthetize them and sometimes unpack them and repackage them in their gear to move them through some of the dry chambers and things. So I didn't want to overwhelm those guys, so we tried to space them out. But it seemed to work out at forty five minutes to an hour, so there wasn't

a lot of time to relax in between. I mean, we gradually we're getting colder and colder during the day. Of course, we're in the water for all of that time, and the water was twenty three degrees, but we only had had thin tropical wetsuits on, so it was pretty shivery. By the end of the last boys, I'm pretty ready to get going as soon as the last kid's done.

Oh my gosh. Well, I just I could talk to you about this forever. It is so so fascinating to me.

But I obviously appreciate this is probably not the first time you've talked about it in this level of detail.

No, it's become a bit of a thing, but which has changed my life, you know, honestly in so many ways that I never expected when I attended this rescue. I can honest say that Craig and I went over there we looked at it as a job that we could get involved with, that we could contribute to, and it was a bit of an adventure. But we had no understanding of the size of the story and no

expectation that that was the case. And I was quite appalled actually when I got home and found that there was all this media attention and focus on us, I just really well, I actually did quite a good job at hiding from all the media for at least sort of two to three months, and it was only because of the South Australian of the Year and Western Australian of the Year awards that we received that we started to feel like we couldn't really hide from it much

longer because it would seem a bit rude if we've been giving it an award and we wouldn't even talk about it, So we kind of had to roll over in the end.

Well, I think that's also another interesting thing, and that was my next question for you. Was after an event like that, one of the other books that I have read many many times is called Emergency Sex, and it's

got nothing to do with sex. It's just obviously guess your attention out four different UN workers who go on these expeditions rescue missions in all the major war zones of sort of the last twenty years, Rwanda, Cambodia, Somalia, and how they just spend their whole trip trying to get to safety, and then they get to safety and they can't deal with normal life, so they find another war zone and they all keep finding each other thinking.

What are you doing back here? We just got you home safely? Was it hard for you then to go back.

To normalcy after, you know, back to Little Adelaide, after this global scale operation and that adrenaline.

It wasn't really because, as I said, I just put it. I was able to put it in the workbox, to say this is you know, this kid's my next patient. Okay, this is a slightly strange operating theater and the risks are a bit higher than usual for one of my awn anesthetics. But nonetheless, that's the way I compartmentalized it end my brain and the way I dealt with it, I think. So when I came home, I thought, well, I'll probably I might give myself a long weekend and

then back to work. And you know, and that's the way I was to work. Well, I got home on the Friday night, and I thought, I'll take Monday off, treat myself to a long weekend, and then go back to work on Tuesday. Stop it. And you know, that's just the way I was thinking about it all. I didn't think it was that big a deal, honestly, and I thought we'll probably get a nice letter from you know, maybe the premiere or something saying good job.

Meanwhile, you but the Australians.

It just went mental. Well yeah, and all of that was completely unexpected.

But very very well deserved.

I've been shared Australians of the Year last year. You both Order of Australian Metal. You're an OAM now, is that right?

That's right, you're a royal. I kind of remember what the tie some super long title, but it's very fancy.

It's very cool. It is very nice and you get a sash, so that's good.

I've read about the sash.

I was like, that is so regal and tie of them to do. And then the aneth Tist British organization thing that was named after the guy who did all the.

Test about yes, the Edgar Pesk Citation, which is my favorite award of all of them actually because Edgar Pesk was a physiologist in the Second World War who decided he was asked to prove that the May West life jackets would support an emmon who had gone down in the English Channel if he was unconscious, to prove that these life jackets would keep his head out of the water.

So he said, well, the only way to prove that is to have someone anesthetized in a pool wearing the life jacket, and of course I can't ask anyone to do that, so I'll have to get myself anesthetized and get in the pool. So he is the first and only person that I'm aware of prior to this rescue who has been anesthetized and then intentionally put in water, and so he has always been a hero of mine, and that kind of has come the full circle that I ended up getting that award, which was really nice.

Yeah, and you are now a hero to so many. Honestly, I know, I love how humble you both are about the whole thing, and the way you write about it is just as if it's like I mean, you express the grandiosity of it and the challenge, but in a way that makes you guys seem like just so humble about your role in the whole thing, even though you are actual Australian hero.

Well, I think cave divers like problem solving, and all the guys there, the British and the European cave dives, they're all the same. They just looked on this as a gigantic puzzle to somehow solve and to work out how best to do it. And fortunately for us it seemed to work. I still don't really understand how, but I'm happy that.

You're happy to go with it.

So the final section is called playta And I don't imagine that you actually have any time for any real pursuits outside of being an actual doctor and an ethetist as well as a cave diver and now in Australian of the Year.

But what do you now do for fun?

Is there anything when you unwrap Harry doctor, Harry, cave diver, Harry all the roles that you wear and Harry dad and Harry family man, like, is there anything that you do that's.

Just for your own joy?

Do you have well Flix, I have to see. Oh yeah, I do like on Netflix. I mean, I'm a very keen photographer and underwater videographer. So my secret path is that i want to make documentaries about our adventures. And I've actually been well, I've been trying for about ten years,

but of course had many many rejection slips. But the great thing about this adventure is that it's opened a few doors for me in that regard, And until COVID started, things were actually starting to progress quite well with a concept for a documentary series. So I'm that's still on the table, but has just had to be put to bed for a little while until the nasty virus goes away. The other exciting thing that I've just started is I

had my first fora into motor sport yesterday. I've bought an old I've bought an Old nineteen sixty eight mini, and yesterday I did my first hill climb event in it. Absolutely loved it.

Oh that's so much fun. See.

I love again that between doctoring and water related things, you have another hobby.

This is amazing.

Well, my wife, actually I meously does worry about my cave diving, obviously, especially when I go away out of out of range on some major expeditions. She does worry a bit, and strangely, yesterday she came to this track to watch me, you know, just in case I've rolled the car or did something crazy. She said, you know, this is so much better than cave do I'm not worried about you at all doing this. You compare it because I can see you. I can see you in

this funny old little car. It doesn't seem to go very fast.

And with the documentaries, I saw that James Cameron wrote your forward, so I feel like you've got more than a good foot in the.

Door in that department.

Yes, it was quite a nice I'd worked with him on a couple of little things. Well, he was working on some very big things. I had very minor roles in them. But so I had met him before because he's actually a very passionate ocean explorer himself and he loves everything about diving. So he was very generous to actually give me a call after the rescue and say well done, and gave me some advice about the media and so forth, and so I thought, well, maybe I could just ask a favor back to him and asked

him to write the forward. And then I've just interviewed him for my podcast. So no, so that is super exciting.

Oh my god.

Well again, Okay, Also, guys, he's also managed to squeeze in a podcast on the side. I don't know how, but this is absolutely amazing. Is that what your next big goal is? Documentaries?

Podcast?

Yeah? Well, I am quite enjoying all the media side of stuff now, and doing a podcast has been a real challenge. Yeah. I'm quite a nervous interviewer. I don't like the way I talk, of course, and like nobody does. And I I'm an R all the time, but I think it's really good for you to do stuff like this too. If you think you're no good at something, the best way to fix it is to just do it. And so in the COVID madness, so I was sitting around thinking, Ah, I think I'll just do a podcast,

see how that goes. And had I known how much work it was, Sarah, as you probably already could have told me, maybe I wouldn't have rushed into it. But I've done twelve. Now can I give it a plug? It's called Real Risk.

Oh please do.

I basically talk to adventurers about risk taking and how they perceive risks and things and how they manage them.

Oh. I actually, I'm just going to binge. I'm not going to sleep tonight. This is all I'm going to listen to.

Start with number twelve. James Cameron.

Oh he is the most recent one.

Yeah, Oh wonderful?

Is that? One of the weirdest things that happened afterwards? Like who else called you that you were just like, how do you know?

OK? The weirdest thing that well, not quite the weirdest thing that happened was meeting Harry and Meghan at Admiral t House in Sydney.

Photo is it?

There is? Craig and I are just having a stubby and we're chadding to Harry and Meghan. There we are, and they're just like, oh, hi guys, how are.

How you doing?

Harry said, I love afternoon tea in Australia. You get a beer.

Oh my gosh, what an incredible journey. I just have so much admiration for you. Very very last question. I'm so grateful for your time, but I would love to know three interesting things about you that don't normally come up in interviews because I feel like you get interviewed a lot, but people would ask a lot of the same questions. So what stuff that doesn't come up that's interesting about you? And you can't use the bird thing because I already said.

That all right, Well, I think the motorsport's a new thing because that only started yesterday.

Yeah, that's exclusive content everything.

And I don't I'm at least what would she say? Well, snore like yeah, snore like a train, like a train. In fact, last night she said, do you remember me waking you up and poking you and telling you to roll over? Because I thought you were just about to stop breathing. I do love my food, and so I tend to get a bit fat if I'm not if I haven't got a project. Sometimes I get into running, and I got up to like thirty three k's run

like I've just got OCD. I think, whatever I do, I'll throw myself into it, and then I suddenly get sick of it and I'll never run again. And that's what that's the phase I'm in right now. We're not running phase.

I love how they're in Craigs chapters.

There's a few little subtle digs that you're getting back into your wet suit and oh, I can tell you guys.

Are good mate.

It's a long running thing.

Husbands. And since I love quotes so much, what's your favorite quote?

Well, it's a complete cliche, but to me it's become more and more obvious that it's true. And that is what doesn't kill you makes you stronger, and that's perfect

for you. I think. As Australian of the Year, the message I wanted to get out was to young parents and to kids that it's very important to get outside, have some adventures, take a few sensible risks, get off your screens and explore your local environment, whether that's jumping on your bike with your best friend and riding up to the park and damming up the creek and catching frogs and all that stuff that kids should be doing instead of playing on their computers, and to the parents

to let them go and ride their bikes around. They're not going to get snatched by a predator, They're not properly going to get hit by a car. And you know, I'm a parent, and I know it's very hard and there are risks out there. But without risk taking, we don't become resilient, we don't become confident. We have to do things that challenges and can be hard or uncomfortable,

and that will make us overall much better people. So wrapping kids up in cotton wool and hovering around them, not letting them even get a scratch, actually will make them much worse off in the long run.