[Music]

Monster House Presents It's actually quite unlike anything we've ever seen before. A giant hairy creature, part beast, part man In Loch Ness, a 24-mile long bottomless lake in the Highlands of Scotland lives a creature known as the Loch Ness Monster. [Music] Monster Talk Welcome to Monster Talk, the science show about monsters. I'm Blake Smith. And I'm Karen Stolzner. We've been doing this show since 2009. That's a long time, but not even close to as long as I've been fascinated by monsters.

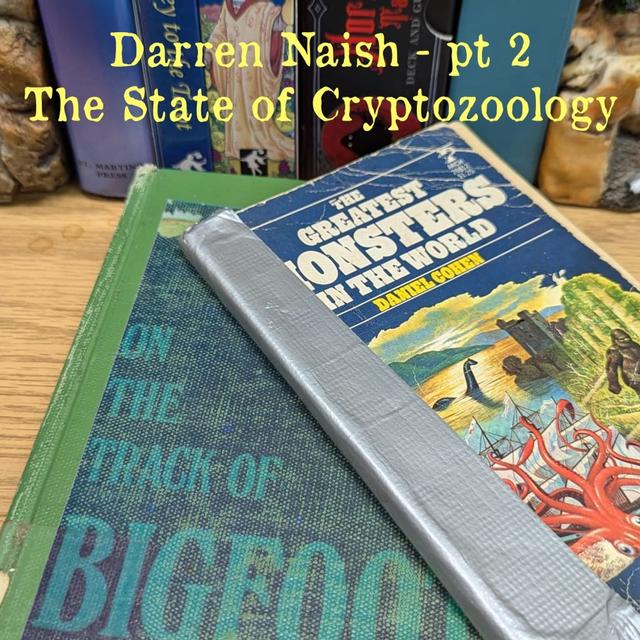

That got started way earlier. I have a tattered copy of a paperback book from Daniel Cohen titled, "The Greatest Monsters in the World" that I bought at the school book fair. Let's see, it's copyright says 1977, so I assume this would have been in the second or third grade. The covers fall in a part held on by a piece of tattered grade duct tape. And inside, I've written my name in three styles, including a rudimentary cursive, which makes me think it was probably third grade.

The point is, the point of that is this. When I first got involved in thinking about cryptids, it was in probably the heyday of the field. It was after the coining of the term cryptosoology, and it was after the Patterson Gimlin film. Another early book that I encountered in the first or second grade was on the track of Bigfoot by Mary and Place. I have a copy of that too. Published in 1974, this green fabric book was one of my gateways into Bigfoot.

I'm whole to get in my hand right now, and I'm amused to see that in the last chapter, it's talking about a young and enthusiastic Bigfoot research named Tom Biscari. Yeah, that's Tom Biscari. Writing a typo into an early bit of Bigfoot fame. It's not really the author's fault.

She's clearly quoting from an newspaper article that I tracked down to a 1973 issue that messes up Biscari's name leaving out the D. Now this amuses me so much, not the typo, but that right now it's the same rag-tag band of misfits, enthusiasts, grifters, and true believers that have been around all this time. The old guards dying off, but the messy mysteries and the tiny fiefdom feuds continue across Bigfoot hunting groups.

While at the same time, the larger story of cryptosoology seems to be blurring into a pop culture potluck. So this buffet of buffoonery includes everything from the sincere amateur scientist to the most gullible gobler of the fantastic, and somewhere in there is still the cryptosoology core, the people who are looking for real animals in these monster stories. But all around that, there's this frenzy of folklore fantasy and confabulation.

If you study this stuff long enough, there's a few reliable character arcs that play out. One is the never-give-up diehard Bigfoot believer. Now this doesn't have to be exclusively about Bigfoot believers. I'm using that for a little bit of a straight-up purpose. Then there's the Bigfoot burnout. This hits a lot of people when they start with an open mind, but get tired of the hoaxes and the ambiguity of the evidence and all the infighting.

And then there are the paranormal proponents, people who may have started out looking for something normal, but have to account for both the lack of physical evidence and the weird supernatural stories that accompany classic hairy hominid tales. What if it's not just an animal, but something supernatural or extraterrestrial or ultra-dimensional or even demonic? The paranormalists can stomach those elements without a hiccup. And of course there are the deniers.

It can't be a real animal, so it's made up types. That's not enough though, discussed by the lack of plausibility, they often denigrate the entire field as a pointless waste of time. And sometimes these folks are broad spectrum cultural dismissers of anything they deem irrational, and that includes religion. Now I know a lot of these folks, but I think they're missing an important point. Namely, the Bigfoot stories don't care if you believe in them. They don't care if they're implausible.

They are stories and stories are vital to the human experience. I don't mind living in a world where Bigfoot is not real, but I feel richer for living in a world full of Bigfoot stories. But let's get back to cryptic zoologist's whole. Is cryptosoology slouching towards bedlam? I'm gonna keep exploring this question because it's an evolving one and seeking lots of voices might help me reach some personal consensus view. Right now I'm not sure.

The pedantic side of me says that if you're not looking for a mundane animal, well then you're not doing cryptosoology. But the big tense side of me says let all the stories come in because this is ultimately a cultural matter and not a cryptid matter. I love monsters and I love people and I just want to understand so I will continue these questions until I stop being curious.

Which I hope is co-terminous with my own life because servicing my curiosity is what makes this whole journey worthwhile. This is part two of a conversation with paleontologist Darren Nash. We're continuing our dogman discussion so be sure to listen to part one if you haven't. By talking about these questions of where cryptosoology is headed. I think it's an interesting question and I appreciate very much Darren's willingness to engage it.

We're not even close to being done with this topic though so stay tuned for future conversations about what's next for cryptosoology. Monster Dog. I first had you on the show back in 2010, episode 21, it doesn't seem like it was that long ago. But yet it feels like cryptosoology has really changed and I think this dogman stuff is a perfect example. It felt like growing up, you know, cryptosoology was about real animals and are animals that might be real.

And I don't know about your take on it but it feels like over the past 15 years or so. There's been a lot more portals and weird apports and supernatural stuff and demonic influence. Is that your vibe too? What do you think is going on with cryptosoology? Yeah, yeah. It's a thing I think about a lot. And my get out of jail free card is the fact that I've always said as long as I've been writing about cryptosoology and publishing on it.

I've always said that I feel that my ideas on this are just constantly evolving, constantly changing. When I first became interested academically in the field and I was very young. I was late teenage years at that point. I was publishing on this stuff when I was as young as 18, which is a god, one of the mistakes that was. Like many of us I became interested in cryptosoology because I had read, I hadn't actually read any of the classic books like those by Hoothelman's.

But I had read enough stuff to make me think that these claimed creatures are real flesh and blood animals were waiting discovery, became interested in it because really enjoyed the kind of theorizing. And let's look at all these, you know, this vast pool of anecdotes and eyewitness encounters and what creatures await discovery. And moving now into kind of like the early 2000s, I'm thinking that if you accept that a large number of flesh and blood animals await discovery, well wait a minute.

I think kind of the anecdotal support for let's say yeti's and various kinds of sea monsters and lake monsters is not tremendously different. And there's a couple of caveats in here that were skip over for now, but it's not tremendously different from a lot of the work that qualified zoologist, naturalist, natural historians do.

When they go to, you know, some island in the south Pacific, they see some small brown bird and they come home and say, you know, there's this small brown bird that we've got to find on, you know, imagine a tropical island. Or whatever. And I obviously because of the influence of Roy Mackel, Bernard Hoover, Merns, Carl Schuiker, Michael Broy, list of other authors.

This is clearly a branch of zoology, cryptozoology is the study of animals that await discovery. So I did as much kind of promotion as I could that cryptozoology is a part of zoology. That was that was the view that I really wanted to promote. I deliberately, I think there's articles I published probably around about 2006, 2007 where I'm saying that version of deronace is saying that we shouldn't refer to this as monster hunting.

We should stop using the term monsters in connection with cryptozoology because people are looking for looking for animals and these animals, whatever, you know, name your favorite cryptid. The evidence for it is not that different from the hypothetical small brown bird I mentioned a moment ago. And I wasn't the only one saying that I was working and co-authoring with other people that were pushing the same thing.

Let's, let's, let's, let's, let's, say and ties cryptozoology. Let's make it, you know, more, more mainstream. Well, today, you know, that doesn't seem like it, but that's actually decades ago now. How, how's that, how's that worked out there and how's that gone through? Well, it's like, it hasn't, that's not what's happened at all. There, there hasn't been any, you know, movement towards increasing scientific acceptance of cryptozoology.

There is nobody that's out there finding and naming like, equates normal animals, like the hypothetical small brown bird that are happy to call those animals cryptids or call them self cryptozoologists. The only people that are doing cryptozoology who are talking about cryptids are basically monsters.

We are talking about the search for monsters. If you are looking for an unknown small lizard or bird or, you know, you know, goby that belongs within a group of recognized species of that sort, that really isn't cryptozoology. That kind of is actually normal zoology.

And I have, yeah, more than happy with it. I've not kind of, you know, been dragged into this view kicking and screaming, but I am far more accepting of the view today that cryptozoology really is about the, it's a sociological study that basically involves elements of folklore that do overlap with natural history and zoology, you know, people are seeing real animals and misinterrupting them and there may be some new species in there, but, yes, it's not, it's not standard zoology.

And then also finally, you already touched on this, the fact that a, a chunk of the stuff that we call cryptozoology, very much is not just non-scientific, but is often almost anti-scientific. The fact that that is there, that's now prevalent.

A big chunk of the discussion, you know, where people are talking about cryptozoology and monsters and how we should interpret them is not happening in a world inhabited by natural historians, or just naturalists, herbitologists, or let's all this, etc. is happening among people who are framing these things as, yeah, related to a spiritual view of the world, a paranormalist view of the world basically.

And I think in the time that I've been interested in cryptozoology, certainly this century, there has been more of a paranormal creep, more of like an idea that, you know, we haven't found compelling scientific evidence for Bigfoot. Well, maybe that's because it's not within this realm. Maybe it's, I mean, you've heard all these kind of, oh yeah, explanations have been put forward.

So, well, it is funny though, because if you accept that they might be real, like real creatures, but they never leave evidence, or the kind that you could reproduce or use to track down an individual specimen. You really kind of face with a couple of options and one of them would be, well, you know, they are actually a culture or psych, their cultural or psychological phenomenon, not a physical one.

But the other flip side of that is they are supernatural or advanced technology way beyond our kin, you know. And neither of those are particularly provable, but one of those falls within a more naturalistic explanation. Yeah, yeah. So, I kind of find myself landing on the cultural hypothesis and the psychological, but also it's not really safe to say that there is a single explanation, because it's not a single kind of story.

And it's like, I don't ever want to push anybody to saying what's your explanation for Bigfoot, because it's a million things, you know. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I very, very much agree in it. That's why I always feel like my views when I'm asked about the subject, me and, or a lot of the place, because I just don't feel like it's tidily, you know, you can't tidily pigeonhole this field into, yeah.

And, you know, the effort that I was talking about from the early 2000s by myself to try and make cryptosology part of zoology, I always knew that wasn't right, because obviously there's this massive, like, folkloric cultural component to it. For certain mystery creatures. And, yeah, today it's obvious that I think that is a larger part of it. It's, yeah, it's a, it's a cultural field, a socio-antibological one.

Yet, it's not fair to say that it doesn't include zoology naturally, because, because those, those are involved in it. My views, you know, most recently been put together for an article I wrote in Biologist magazine published 2022. Pretty good to get, you know, quite a big deal to get an article on cryptosology into into that magazine.

Yeah, it's called a cultural phenomenon, I think, that the type of the article. But, but yeah, that it does push that it pushes that spoiler, but shouldn't you pose that a question? To get people to click on it. Maybe it's, well, 2022 feels like old hat now, anyone that would have read it already has, but, yeah, I wouldn't, yeah, it still does have.

There is still a zoological component in at least some, some parts of it. And I, and I, you know, obviously there are still creatures of interest to cryptosologists that are, you know, investigation and discussion of them is more about normal zoology.

Yeah, that is the case for, for phenomena like dog man. Well, you've got alien big cats. And that's just a load of fun. And, and, you know, those you can sometimes you can get DNA. I don't know, I'm a little concerned about where it's collected, et cetera. But I mean, it's still it's not biologically implausible that there's big cats.

Sure. Okay. Which is very, very interesting. Yeah, that, that, that's a good example of, of a mix and match. I mean, I think there's a valid biological slash zoological phenomenon. There is a cultural element at play which is fascinating. And again, understudied. Like there's, there's actually you could, you could write again. You could do a whole proper study on this. There's, there's views in parts of Europe, including the UK that panthers are kind of a part of the landscape.

Kind of in a sort of like weird conspiratorial sense because rich people are supposed to have owned them and deliberately released them to terrorize peasants. That's kind of an idea that goes back hundreds of years. And it's sort of carried through to modern times because today, I think, I think this was studied in France. There, there were actually groups of farmers up in arms because of, are you aware of the rewilding movement?

I am. I recently became aware of this. Yeah, I was, yeah, we were covering it on in research of because there was an episode about wild children and they talked to a scotchman who was trying to, he was, he was rescuing wolves, but there was also like modern Scottish rewilding of wolves movement. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. So, you know, some people, like people that work on the land, you know, farmers and whatnot don't want.

Links is and wolves and wild boar and moose and so on to be reintroduced to places like France and the UK. And there is, I'm not saying this is like everyone interested is endorses this, but there is the idea that the reason that we've got panthers back here killing our sheep is because.

Well, the ecologists are deliberately releasing foreign animals into the landscape and that's making our life harder so even, even whether there are real panthers, you know, whatever they are, lipids links is whatever, even if you do have that as a valid phenomenon and again, it's biological phenomenon, even if you got that, you still got this sociocultural phenomenon operating, you know, in the minds of all the people without, yeah, yeah.

Yeah, in the US, the big one, the frequently encountered conspiracy is they're here, the like mountain lions and unusual places, I guess would be our thing. And the argument is that they exist, but that the, the state or the federal game regulatory agencies don't want to scare people so they deny their existence. Right.

You know, so, you know, again, always you just need a corpse to sort of disprove that, but I guess one thing about cryptosoology is I've always wanted to be more of a science and I thought if you know people think their amateur scientists when they're going out to look as opposed to monster hunters, it's a different take and you would want them to have some basic scientific training.

You know, how do you collect a sample? How do you let people know when and where it happened? And I've always had this sort of dream, as he always, at least since they've been doing this show, that there would be some way to do sort of a DNA survey of the Pacific Northwest, you know, that if you're going to go out and look for bigfoot also take samples also note where you got them, you know, in like put that in it now because of EDNA that could actually happen, but that's not at all what we see in bigfoot culture, what we see is something different.

It's I call it larp camping, but it's basically people going out in the woods with thermal cameras, banging sticks, making bigfoot hals and if you hear a bigfoot how and you hear a wood knock, you know, how do you know that's a bigfoot in not more campers? I don't know. It's very, it's very confusing.

Yeah, I'm with you on that. And I mean, if you go to bigfoot conferences and such at the moment, EDNA is, it's the, it's a, because you don't know environmental DNA, DNA collected from the environment, including even from the air, not just from the soil and water, but so. Yeah, it's one of the most popular. Yes, it's the new buzzword. Everyone's talking about it.

So, yeah, kind of two parallel things. The people who do have the know how the, the, the tech, you know, the smarts to go and collect data and know how to study and publish it are for the most part so busy with other stuff that it's that's just not on their agenda. If you are an ecologist studying, you know, you name it, the ecology of Sequoia trees in California, you're working pretty flipping hard to get that work done.

There was no money in scientists, very hard to make living in science. And how do they afford to build all their ivory towers, then tell me that. You get those, you get those for free when you enroll. It's the upkeep, there's the expensive thing, especially what with, you know, certain recent political events in the United States have happened over the past several years.

It can be hard to make a living in science. So I think if you are scientifically qualified, if you are invested in a certain, you know, involved in a certain field, then. You are not going to be able to make the time to like, hey, let's, let's for fun. Let's just collect some samples and see if we've got some primate DNA or alien, pat the DNA or whatnot.

So you've got that as, as one strand of what I'm describing it. The second thing is you do have a large number of really interested and often dedicated amateurs who are going out into the wild and hoping to look for, you know, big foot and other cryptids. And as you said, a lot of this does look like does look like, larping it really does. Many of them are doing the right things that they should in order to behave as citizen scientists as amateur scientists.

And if you listen to enough people in like certainly the big foot community, they're obviously the most visual here. So, the elephant Bobo mentioned is quite a lot of times on their podcast. People are, you know, encouraged to collect samples and, yeah, to think about things in a scientific way, to think about constructing and testing hypotheses.

The problem is that although I think that the, the amateur, the citizen, um, scientist is now aware of this more than ever, they're still, there still isn't enough expertise on their part to know what to actually do with data once you get it once you get it. And by the way, I'm not saying that it's a problem that they don't like, you know, get valid evidence of the existence of, I don't know if you told my big foot, but they don't get valid evidence for it.

The fact that there is evidence of any kind, even negative evidence is still kind of, you know, a result of a sort. And potentially still something publishable, what I've discovered is that these people don't know how you actually get things into the, the canon of science, how things actually become scientific. I've now done field work with quite a few people really interested in in, in, in behaving as citizen scientists, they might have a very biased approach.

They might be true believers when it comes to the cryptids concerned, but they do want to kind of do things like by the book, but they don't know how to actually get things, you know, involved in the process of science. You don't publish things in popular magazines and blogs and that's the end of it. You do have to try and get stuff into the technical literature for work in scientists that is tremendously hard.

I mean, actually getting stuff finally publishes is really hard, even if you know what you're doing. So I don't have an end point where I'm going with this, but I'm saying there's these two parallel things. There's the people who know how to do it. It's really hard, but they're not going to be spending their time on the cryptosolid stuff.

And there's the people who are spending the time on the cryptosolid stuff, but aren't matching up with the qualified scientists to have a result that is like, viewable to humanity as a whole. I guess I've always thought, or I have long thought, that if those two groups could somehow work together at all, even if you don't find a big foot, you might find some really interesting biological data.

And I think that would be awesome, you know. Would it be worth the investment in time? I don't know, you know, maybe not, but maybe, I don't know, it depends what you find. I mean, you would probably get a lot of really interesting information about the sort of genetic population of areas that have gone relatively unstudied. And that's certainly valuable in the big, big data sort of sense.

I think part of the reason this is really hard to match those two areas up is because of like basically how careers work. Then can you as a working person take time out of your life and go and spend, you know, like a month in the Rocky Mountains or in Central Asia or whatever, like looking for stuff with pro cryptosolid people? Yeah, most of us just can't do that.

And the number of people that can do that or can do it in some form, a really few in for a between, you're talking about a tiny number of people worldwide. And we went to to jikistan last year with, I'm sure they weren't mommy saying this, but you know true believer cryptosolid people with a Richard Freeman and among others. And we collected a whole bunch of interesting information.

I'm not sure what way it goes. I don't want to talk about all the results here because we do still aim to publish it. But we collected anecdotal information, you know, which to me felt a bit more folklory and a bit more like ethnographic than biological, but nevertheless it was data from interesting areas relevant to the belief in the cryptids concerned. And our mass type, you know, wild man type creature and claimed late surviving Cassie and tigers, you know, we did collect information.

And my aim as someone who publishes fairly regularly in the technical literature is is to get it written up and published. But here we come back to what I was saying a minute ago about, you know, when people do this in their lives, I've had this data since last year. And I haven't yet had time to finish the paper because the way my life works, I just don't have time to sit down and write papers on something that's really extraneous to everything else. Totally understand.

Yeah. It takes me sadly years to get my, I have an idea and then it takes me five to ten years to get it done. And then when it's done, it feels like, oh, that didn't take long, but it did. It took a long time to make chunk of your life. It really is. Well, you mentioned Freeman, it reminds me of the British 40s. Are you still in touch with sort of the 40th culture over there? I've been wondering if I'm a big fan of 40 and times, but it feels like those are all people, my age and older.

Are there still young people becoming 40s? What's the demographic? What's the culture like these days in the UK? Yeah, that's an interesting question. So, I mean, so on the first thing to say is, yes, I am still in touch with a lot of those people, talk to them fairly regularly, talk to quite a few of the people who are involved in putting together 40 and times.

I'm still in touch with, well, I am regularly in touch with quite a few people that are in the UK and elsewhere in Europe, fairly well known for their interest in cryptosology. The fact that we no longer have a really important part of maintaining a community of like-minded people is you need to have the opportunity to meet up. It's tremendously difficult to actually just go and travel half across the country, just go and hang out with someone.

We no longer have unconvention, the 40 and times meeting that died some years ago, which was a real shame because that was a real hub. And John Downs of the Centre for 40 and Zoology used to run an event called Weird Weekend, and that no longer happens due to where John is in his own life. I talked to John quite regularly. There is an event called Weird Weekend North, but the UK is tiny, but it's incredibly expensive to move around here.

So I've heard I didn't realise the trains were so expensive and apparently also unreliable, so this was all news to me. Oh yeah, it's like, you know, I don't drive, so I don't want to rely on my wife to take me everywhere, but a trip of like 200 miles for us is, yeah, you wouldn't want to pay to travel by public transport, I think you could have been unreliable public transport. We don't have a regular sort of monster themed, cryptoswoldy themed meeting, which is a problem.

In terms of young people, that's a really interesting question as well because, you know, the people we interact with, our view, our vision of what, you know, a community is like is sort of dependent on where we are ourselves in life. I'm in my 40s, most people I know are sort of similar age to me, I don't hang out with like teenagers in 20 year olds, but I am not aware of that many young people that are kind of coming into this.

I do see quite a few people on social media who are young and who are quite interested in the history of flesh and blood cryptoswoldy. A few of them have even published things in it, so actually the more I think about this, I think that there are, yeah, at least some people getting into this.

Interesting. I mean, I know we have a lot of young listeners on Monster Talkers, so I always want to encourage people, you know, to be interested in these things, and I just like to use some critical thinking about, you know, how to approach it, but these are the stories that have entertained me my entire life, so.

Yeah, I don't want them to die out, but I also kind of don't want them to turn into weird supernatural stuff. I still, you know, well, I think like the impression I get is that we are among the younger people I'm thinking of, I've got a whole list in mind, actually, the more I think about it, I don't want to say their names, I'm really, I'm going to get them wrong, but.

They really are living in post cryptoswoldy, they really are living within that space and talking about, you know, this discussion of Monster's Cryptoswoldy today goes hand in hand with speculative evolutions, you know, an interest in imaginary aliens and science fiction, knowledge of the animals of the past.

I think it's seen that, hey, wow, there was, you could be there's, there's many people that are interested in, you know, paleontology and the history of thought of on evolution and say that wow, there was a time, there was a time in the 1930s where people had this particular model for human evolution say and it's not that different from that, that's a completely respectable thing that could be discussed in any.

And so, you know, the anthropological technical journal, you could talk about that and at the same time you can say there was a time in the 1950s when people honestly did, you know, burn it, who moments is hypotheses were always couched in his big picture evolutionary scenarios like the yet he's not just a mystery primate is a specific kind of mystery primate that tells you something about the, you know, the evolution of of primates and there's a bunch of whole processes that have led to it being the way that it is.

The people I'm thinking of are living within that space, so the, the tech, zoo con tech, biology, convention event that I run, we've got the next one coming up at the end of September this year in London, Bush House in London, I aim for probably next years meeting to be more monster cryptozoolgy focused and I'm hoping there to get a whole bunch of people that work on monsters, the science of monsters.

And the people I'm thinking of, the number of people researching this, you could, you could have like a pretty good, good number of speakers on session. Oh yeah, that would be awesome. I'll keep you posted. Please do, please do. And I'll put links to your article about dog man and links to your Ted Zookon all in the show notes. So, listeners can check that out. Darren, I love talking to you.

I know we don't get to talk much, but I always feel like we're close and it's really funny because, you know, between listening to your podcast, which I hope you get to come back to someday. And other things, I just, I know we have so much in common, so I hope someday we get to meet in person. Back at you, man. Yeah, I really enjoyed Zookon Chief. Thank you, thank you very much for having me. Really enjoyed it. Monster Talk

You've been listening to Monster Talk with Science Show about Monsters. I'm Blake Smith. And I'm Karen Stolzner. You just heard part two of my interview with Darren Nash. We started out in part one discussing the history of dog man, and here in part two, we were discussing the current state of crypto's wallogy. What's next for the field? Who can say? But I hope to be here to talk about it, and I sure hope you'll be here too.

Monster Talk's theme music is by Pete Steeling Monkeys. If you're hearing this, then you got through our service chain successfully, and are getting episodes via the new feed. And if you're NOT hearing this, then who was phone? [Music] [Music] [Music] [Music] This has been a Monster House presentation.