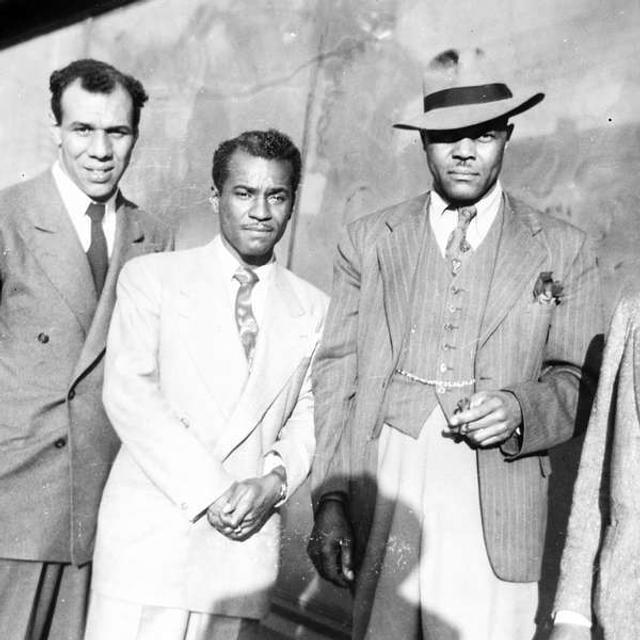

what they had on each car was called a jump seat and is about just wide enough for you to sit on they call it a jump seat because The bell would ring and you'd look up on the board and you see, okay, I had to go to this room. So you jump up and then you're that seat that was on a, on a hinge and it would jump back up into the wall. Right? That's Warren Williams. His Uncle Lee was at the forefront of the drive to organize sleeping car porters in Canada.

An important and timely story as Black History Month draws to a close in both the United States and Canada, where today's show originated on the On the Line podcast. And on Labor History in Two. the year was 1969. That was the day black food workers went on strike at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. I'm Chris Garlock, and this is Labor History Today.

Hold the fort, for we are coming Union hearts be strong Side by side, we'll battle onward Victory will come Look, my comrades, see the Union banners waving high Welcome to another edition of On The Line, a podcast that focuses on British Columbia's rich labour heritage. I'm your host, Rod McElgora. February is Black History Month in Canada. On The Line has marked the occasion this year with a look back at the fascinating history of sleeping car porters, almost all of whom were black.

They were essential during the heyday of overnight train travel. It's a story that has only recently started to be told, combining the history of black employment in Canada, unionization, and the fight for dignity and equality on the rails. Kudos to the CBC for its current series on sleeping car porters called simply, The Porter, Recommended. We examine those long ago days.

Mostly through the voice of Warren Williams, whose uncle, Lee Williams, was in the forefront of the drive to organize the sleeping car porters. Warren is currently president of QP Local 15, representing inside workers at the City of Vancouver. But in the early 1980s, he worked for the railways, including a short time as a sleeping car porter himself. By then, thanks to his Uncle Lee and other porters who stood up to the railway companies, much had changed for blacks on the rails.

What follows are excerpts from an interview I did with Warren Williams last year. Warren talked about the history of sleeping car porters in Canada and his family's experience on the rails. Beginning with his own time working on the railroad. Oh Lord, I hear that whistle blow. Oh babe, I hear that whistle blow. That she blows just like she ain't gonna blow no more.

But by that time, uh, we had, uh, blacks working, as I said myself as a dining car steward, It's unheard of back in my uncle's day and my grandfather's day. Um, and so you had, uh, blacks working as dining car stewards and as service managers and, uh, sleeping car conductors still didn't have any, uh, blacks working as train conductors or brake men or, uh, Uh, not that I know of, or, um, engineers, or firemen, that was still predominantly held by, uh, uh, white.

There were a couple of Indigenous fellows doing that work in northern BC, but, uh, yeah. Uh, my grandfather, interestingly enough, was very upset when I hired on with the railway, when he found out that I'd hired on with the railway, he was not happy about it at all. At the time, you know, he had, they dealt with a lot of racism, uh, et cetera, and he made it quite clear that that's not something he wanted his grandsons to be doing. And, but he said, Marty, it's nothing I can do about it.

Now you've signed on. I'm just gonna. Tell you how to take care of yourself in close quarters. That's this, that's the truth. He did that. And, uh, and be careful and do your job to the best of your abilities and you'll be doing it better than most and they'll have no reason to come after you. But they will come after you. Yeah. Warren's ancestors on both his father and mother's side fled the racism of the United States to settle in rural Saskatchewan.

A church built by his mother's family still stands and is now a heritage site. Saskatchewan government just recently in the last 10 years or so designated the church that's a log hewn. Church, uh, built, they call it the Shiloh people, uh, by the, my descendants, my grand, my, uh, great grandfather, Caesar Lane, uh, um, built the church and they've just designated it a heritage site.

Uh, and so there's still, uh, and my ancestors, uh, some of my ancestors are buried there in the church, there's a plaque and et cetera. And that's, you know, that's my family. Yeah, it's pretty cool. Um, so what did they do on Hill? And was it Hillside? Yeah, Hillside. They're farmers. They came up with farming. I believe at the time the government was, uh, it's interesting. The government was offering in Canada was 60 acres and a mule. I think it was in the United States.

It was 40 acres and you've probably seen the logo, right? Uh, so that's so that, you know, they're trying to, of course, this is during Jim Crow era and in the United States. And so we, a lot of blacks were, uh, migrating north to Canada. And it got to the point that, um, the Canadian government in 1911 put a ban on, uh, uh, Blacks migrating, immigrating to Canada. They did it for a year, apparently, yeah, apparently for a year. That had an impact on Warren's family.

They had to move in search of work that brought them to the railroad because, of course, it was hard for, uh, blacks to get work. Right. Um, and so the families eventually either moved east to Winnipeg or west to Alberta and, uh, and like Mount Kali, for instance. His first, he got a job in South Battleford on the, and that's where he got his first job with the CNR and then the family migrated to, to Winnipeg.

Just like a lot of black families did the railway was the hub for Canada at the time and Winnipeg was central to all of Canada at the time. And so everything, basically everything went through Winnipeg at one time. Yeah, both rail lines. And both rail lines, uh, exactly went through Winnipeg to CPR, Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway.

And so the, so my, my, uh, grandfather, uh, Carl Williams, and his brothers, Lee Williams and Chester and all, they migrated to Winnipeg and, uh, started working. On the, on the railway, my grandfather and, uh, one of his, a couple of his brothers, Tommy and Roy, worked on for CP Rail and my uncle Lee, uh, worked on, uh, Canadian National Railways with, uh, and at that time it was, uh, uh, Canadian Blacks, uh, from, you know, that had migrated from the United States.

And or were born here, worked on the railway, and then you started getting an influx of Caribbean peoples, black people from Caribbean, from the West Indies, Jamaica and Nova Scotia started to come to Winnipeg and migrated to Winnipeg for work. They hired on as porters for the railway's sleeping cars. They're all sleeping carporters. My, uh, my grandfather was a, um, he had a trade. He was a stuckler. You might remember what stuckle is like.

And my grandfather did that, that type of work on the side, but he couldn't get work. He was very good at it. And when he did get work, people would watch him work. Apparently he was that good at it and fast. And that was the thing, but he couldn't, he just couldn't maintain work because they weren't hiring blacks in Winnipeg. And the only place that he could get hired. It was on the railway and that's what happened with a lot of the blacks and it was, you know, in the community.

It was, um, a good paying job, you know, a steady work wasn't good paying, but it was steady work, um, money coming into the family. You can raise a family on it and you had a bit of, um, prestige in the community. I don't think I ever seen any of my uncles or my grandfather. at any time else, uh, not wearing a suit, except if they were in the house. But if they went out, they were in a suit, jacket, tie, and off they go.

And that's how they would go to work, and that's how they presented themselves at work. The tradition of black sleeping car porters had begun in the 19th century, when George Pullman invented the pull out berth. Pullman wanted Blacks to make up the berths and cater to overnight travellers, because he considered the job akin to domestic service. Canada's two main railway companies, Canadian National and Canadian Pacific, maintained the tradition.

In an age rife with discrimination, as Warren mentioned, work on the trains was one of the few jobs Blacks could get with steady wages. Daniel Peterson, father of famed Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson, was a sleeping car porter. So it may have been no coincidence that the song most associated with Oscar Peterson was the classic jazz tune, Night Train. But it was far from a dream job. Porters were on call to sleeping car passengers around the clock.

In addition to making up and then reconverting their berths in the morning, They carried and stowed their luggage, pressed their clothes, shined their shoes, for a tip if they were lucky, served them food and drinks, and did anything else a passenger might want. They had to provide their own uniforms, and they had no job security. If a passenger complained, they could be fired. Just like that.

As if all that wasn't enough, shifts typically lasted three days, yet there was no fixed place for them to sleep. You very rarely back in those days, up until 1940, you didn't even have a birth.

And then after 1940, you may get a berth if there was room, but even if there wasn't room, even if there was room prior to 1940, you didn't get a berth and what you, uh, what they have, what they had on each car was called a jump seat and is about just wide enough for you to sit on and it, they call it a jump seat because The bell would ring and you'd look up on the board and you see, okay, I had to go to this room.

So you jump up and then you're that seat that was on a, on a hinge and it would fall, jump back up into the wall. Right? And so that that's basically you didn't you, you slept in that seat. Basically, you didn't, you didn't have even the didn't even have the dignity of having a place to sleep. And of course, you know, like, you're, you're cleaning up people's messes and.

24 7 anytime of day or night at their beck and call without absolutely and you better, you better be polite, you better be courteous, you better be smiling, uh, you better not give them any reason to, uh, be upset because you could, they, you know, they have, they would write you up and 60 merits, you'd be fired. There's no way of answer, but it's about it. And if you, uh, Became what was called in the day too familiar or too friendly with uh, white pass female passengers.

That was pretty much an automatic, you're you're gone, fired, right? You had to act like they weren't there pretty much, you know, and just deal with the man. They're expected to be subservient also, right? Not only to the passengers, but to the white uh, workers on the railway, and of course the employer too, right? So it was not a It was it was um, it was a load that they carried. But they carried it well. Um, and we're proud of the work that they did.

They took a great pride in the work they did, which is why my grandfather put that lesson on me. Do it as best as you can, and you'll be doing it better than most. And, you know, it was, you know, I mean, I had the experience of, uh, being asked by a passenger to shine their shoes back in when I was on the road, and I told them, no, I don't do that. And they were surprised. Sleeping car porters realized early on that they had to fight back against the way they were treated.

In those days, the best way to do that was through a union. But when porters sought to join the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees, the union proved just as racist as the union. As the railway bosses, they turned their back on the porters because they were black. So in 1917, the Canadian porters courageously formed their own union. The Order of Sleeping Car Porters, based in Winnipeg, was the first black labor union in North America.

Two years later, despite the way they had been treated by the White Railway Union, 90 porters took part in the six week Winnipeg General Strike in 1919. Most were never hired back. The Canadian Sleeping Car Porters Union won some gains from Canadian National, but the CPR proved a tougher nut to crack. After 12 union activists were fired by the railway, attempts to organize porters for CPR failed.

They revived in the late 1930s, when the U. S. based Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters expanded into Canada. After several years of secret organizing to avoid being fired, Canadian porters voted to unionize in 1942. It took three years of tough negotiations before they were finally able to sign a union contract with the CPR.

The breakthrough contract gave porters a monthly salary increase, two weeks paid vacation, overtime pay, And at last, a reserved berth on each passenger car so porters actually had a guaranteed place to sleep. One more thing, porters could now put up name plaques in their sleeping cars. No longer would they be anonymous or George, as passengers often called them. The contract was the first time a union organized by blacks had negotiated such a detailed agreement with a Canadian company.

Still, on the job discrimination remained. Black porters continued to be denied promotion. They were unable to become conductors or even work in the meal cars. Warren's uncle, Lee Williams, spearheaded the drive to end this ongoing racism, but it wasn't easy. My uncle.

1930 started working 1930 1930 started working for Canadian National Railways, and he fairly quickly found out that, uh, working conditions for, uh, blacks on the railway were not, uh, nothing to write home about, um, and could see the injustices of it. And initially he initially he, he, he would say that, you know, he tried to just do his job, not worry about it, and just, you know, do come home. Get up, go back to work, do his job, blah, blah, blah.

He didn't, he didn't, uh, really want to pay a whole lot of attention to it, but something, uh, along the way happened and, and he started to, people in the community started talking to him and, and, uh, trying to push him to become part of the, the union. So he became, uh, chairman, I think of the order of poor sleeping car porters and then, uh, went to convention. Because they were allowed to go to convention. So I think the first convention was in Montreal that he attended.

And at that convention, he put a resolution forward to end the discrimination in their collective agreement. And it was ignored the resolution was ignored. And so the next time he went.

To convention was in Toronto, and he put the same resolution forward in Toronto, and, uh, he says that, you know, from what he could see from the raised hands, he believed that they had a majority of votes that the resolution would pass, but the president of the day said the resolution had failed and it didn't pass, and so then that's when he, uh, started looking at, okay, what, what, what can I do? And that's when he started talking to John, uh, Diefenbaker. Yes, that John Diefenbaker.

Yeah. Prime Minister of Canada from 1957 to 1963. Diefenbaker loved taking the train to Ottawa. Lee Williams was often his porter and got to know the garrulous Saskatchewan politician. And then in 1955, uh, my uncle Lee Williams, uh, Who had the fortune, who was fortunate enough to be on a run from Winnipeg to to Vancouver. And he would pick up Prime Minister Diefenbaker when he was an MP. And Diefenbaker and he'd ride the trains going east to Ottawa.

He'd ride the trains, and so my uncle was fortunate enough to get to know him, of course, because he ran, he, he rode by, uh, on the sleeping car, and my uncle would be the porter, so he got to know him, and, uh, He started talking to him about the conditions on the railway and not being able to be part of this, the union and the wage discrepancies and not being able to get promoted and, and being served, uh, food that should have actually been thrown out, that sort of

thing, uh, and the segregation of it. And so Prime Minister Diefenbaker, uh, talked to him about the, uh, uh, Canadian, I think I had it written down. Oh, there it is. Canadian Fair Employment Act. Right, right. And so he talked to him about it and then he told him what he needed to do in order to, uh, present his case, right? And so, through, you know, a few, uh, trips and phone calls, he finally, my uncle, he did that in 1955. And, uh, nothing changed.

And then, uh, less to be Pearson became the prime minister. 10 years later, I think it was 10 years later, Pearson was the prime minister and my uncle Lee contacted Prime Minister Pearson at that time and and told him that he expected that the law will be upheld and given the situation and and four days later, the response from the prime minister at that time was to tell the way, uh, C. N. R. And C. P. R. That they would They would tow the line.

And that's, uh, that they became part of the same collective agreement as the white workers and were able to get promoted. My uncle was the first to one of the first sleeping car conductors and then became very inspector or service manager inspector. Afterwards, they collected, they became part of the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Workers. And my uncle Lee actually became president of that of that union shortly thereafter, because, uh.

The workers realized, white and black, realized that he was actually a fair individual and treated people fairly. And so he, though the white workers were the majority, he got enough of their votes to become president of the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Workers. Winnipeg and Montreal were the main urban hubs for the black porters, but Vancouver was also home to many. A black community took shape in Strathcona. www. un. org Close to the train stations.

There was once a three story building at the corner of Main and Pryor called the Porter's Club, where porters met and socialized during their downtime. Among them was Frank Collins, the eldest of four brothers in Vancouver, who all worked as porters. In the 1940s, Collins was elected president of the Vancouver branch of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a post he retained for many years.

As an interesting footnote, Frank Collins was also the brother in law of renowned jazz singer Eleanor Collins, who recently had a Canadian stamp issued in her honour. She is still living. At the age of 102. For many years, Frank Collins also headed the BC Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, underscoring the close link between the porters and the overall fight for equality for Blacks in Canada.

The small but vibrant black community in Strathcona, where the Collins brothers lived, was known as Hogan's Alley. Warren Williams said it was a real draw for porters making a stopover in Vancouver. That's where they all went. They all went down to Hogan's Alley. Um, Vi's Chicken Shack was down at Hogan's Alley, right? So they would, they would go to Vi's and they'd eat at Vi's. Um, it wasn't until late 60s, early 70s that they even actually, uh, were put up, put up in hotels. To sleep.

They actually stayed, they actually had cars, sleeping cars on at the rail yard where the sightings that, yeah, where they slept, right. But yeah, they would go to advise and they would, uh, Hogan's alley and, and they would go to the cave that the cave downtown was, uh, one of the hubs for, uh, black American and Canadian talents and jazz and blues and rhythm and blues. And, you know, Marvin Gaye was there, you know, uh, the Supremes were there.

What happened when I was a, uh, probably 14, um, my uncle Lee was a deacon in our church, the Pilgrim Baptist in Winnipeg, and we formed the church formed a youth, uh, a youth group and, uh, youth, uh, services. And through that, my uncle Lee and my grandfather and other uncles that were, they worked on the railway at the time, uh, were able to get us all passes on the, you know, they used the family pass and took us all to Vancouver. It took about 30 kids to Vancouver.

And part of that trip was to go to Hogan's Alley. This is the black community of Vancouver. And we went to Vice, Chickashack, and, uh, it was, uh, It was a good, it was a great experience. Actually, it was a great experience. Yeah. One of the things about, um, uh, being black in Canada is we're so, um, now we're so dispersed, you know, like we don't have the same sense of community that I grew up with.

But even with the sense of community that I grew up with in Winnipeg, I took the train when I was 16, uh, to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. And, of course, Nova Scotia is where the greatest majority of Blacks are and were, and it was, it was, uh, even for me it was an eye opener, but it was like being in heaven. Lee Williams left a legacy few can match.

In 2002, at the age of 94, he received an honorary doctorate from York University in Toronto, in recognition of his lifelong commitment to the battle for racial equality. Warren Williams looks back on his Uncle Lee with real pride. Well, I think that, uh, what he really showed people, you know, we are, he refers to himself, and he died in 2003 94, and Throughout his life, he would say, I'm and he believed that people should be treated as equals and people should be treated with respect.

And I think that's, that's the one of the legacies. And the other is if you don't have to settle, like, you don't have to settle. If you're willing to work for it, you can achieve. But it doesn't, it's not just going to be handed to you. So if you're expecting it to be handed to you, it's not going to happen. But if you, if you, if you're willing to, you think that's the big one.

And I think that for a lot of our, our family, especially, especially my age group, and maybe, you know, 15 years younger, my younger cousins, they all learned that. They'll learn that if you're, if you're willing to, if something is important to you and you're willing to step up for it, you can make it happen. Thanks to Warren Williams for adding his take on the history of one of Canada's most interesting unions, which is only now becoming better known.

If you'd like to learn more about Canada's sleeping car porters, may I recommend the comprehensive account by Cecil Foster in his book, They Call Me George, The Untold Story of the Black Train Porters. And thanks as well to my hard working podcast colleagues, Bailey Garden and Patricia Weir. I'm your host, Rod Mickelborough. We'll see you next time on The Line. Horseman's night, we are come, union hearts be strong. Side by side we'll battle, victory will come.

I'm Rick Smith, and this is Labor History in Two. On this day in labor history, the year was 1969. That was the day black food workers went on strike at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Their strike intersected many points central to the social upheaval of the period, including the rights of public sector workers. Besides extremely low wages, workers complained of racial abuse and discrimination on the job.

When the administration ignored their demands, the cafeteria workers sat down at the tables and refused to return to the kitchens. Black women workers like Mary Smith and Elizabeth Brooks organized protests and rallies to build public support on and off of campus. As the strike wore on, many students rallied to their defense. The Black Student Movement was the first campus group to support the cafeteria workers.

Noting the lag of desegregation on Southern campuses and in the South generally, Black students added their own demands to those of the workers. They included the expansion of Black student aid programs and Black study programs. Clashes escalated between students at Lenore Hall a few weeks later when opposing white students attacked integrated groups of students sympathetic to the strike, forcing the closure of the cafeteria hall. Governor Robert Scott ordered the National Guard on standby.

Finally, the workers formed a union and won many of their demands. This benefited 5, 000 other state employees as well. But a month later, the University of North Carolina administration betrayed them by contracting out the food service. Many were laid off or fired for union activities. By the end of the year, the now AFSCME organized workforce struck again over many of the same issues. When renewed student strike support was threatened, management quickly caved and the strike ended in victory.

Like what you hear? Check out more at laborhistoryin2. com That's it for this week's edition of Labor History Today. You can subscribe to LHT on your favorite podcast app. Even better, if you like what you hear, sure hope you do, please like it in your podcast app, pass it along, and leave a review. That really helps folks to find the show. Labor History in Two is a partnership between the Illinois Labor History Society and the Rick Smith Show.

That's a labor themed radio show out of Pennsylvania. Very special thanks this week to the on the line podcast. We've got a link to it in the show notes. Labor History Today is produced by the Labor Heritage Foundation and the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University. You can keep up with all the latest labor arts news. Foundation's free weekly newsletter. At Labor heritage.org for labor history today. This has been Chris Scar. Thanks for listening.

Keep making history and we'll see you next time.