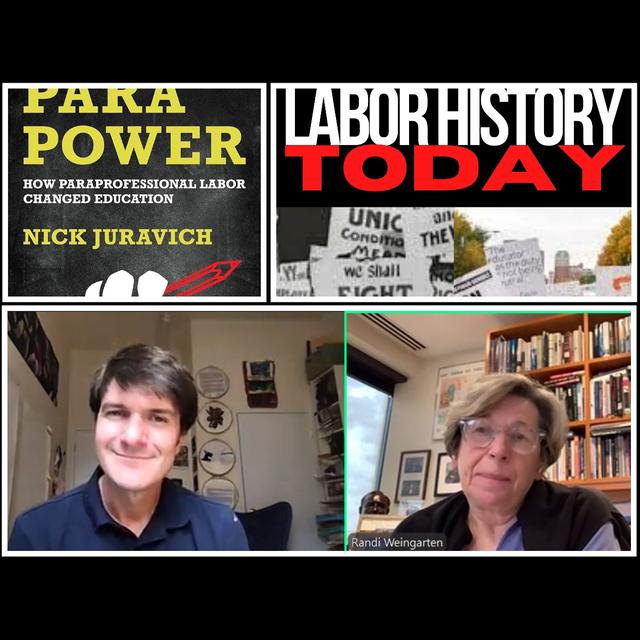

you know, Randy, you are in the book, uh, that 2003 fight, uh, when Joel, Joel Klein tries to fire a whole bunch of paras. I know he's just warmed over. He's just returning to an old party. It was warm over. That's Assistant Professor of History and Labor Studies. Nick Juvi, interviewed by special guest Randy Weingarten. Randy's, president of the American Federation of Teachers and host of AFT's Podcast Union Talk.

We asked Randy to interview Nick, who's also the associate director of the Labor Resource Center at UMass Boston because he's got a new book out we knew she'd be interested in. It's called Para Power, how Paraprofessional Labor Changed Education. Randy and Nick go deep on issues of class, race, and education, and don't miss this juicy tidbit. maybe this makes news. I never have said this publicly. As a Special bonus, Nick shares his favorite labor song, which is now one of mine as well.

I think you'll really like it in our final segment. the year was 1900. Today we celebrate the birthday of Florence Reese, the author of Which Side Are You On's, iconic Labor Lyrics. Which side are you on? Which side are you on? I'm Chris Garlock and this is Labor History Today. Here's Randy Weingarten talking with Nick Jarvi.

So, Nick, it is an honor for me to meet you and I, you know, as someone who, you know, worked for the UFT for many decades ago and who got to know, um, Velma and her husband very well over the course of time, you know, from basically the mid eighties till, you know, till now. Really, um, I was really struck by, um, your, your incredibly capturing of the story of, you know, of paraprofessionals.

Not only in New York City, but also understanding how important the New York City experience was with para organizing throughout the country, but also really understood the struggle and the decision making that paraprofessionals had to make in New York as to whether they wanted to join a teacher's union, which was, at that point, disproportionately white. And, and right in the heels of Ocean Hill Brownsville and where Paris were disproportionately black.

And that conflict at that point was still ever present everywhere. Um, and I just thought that you really had, you know, just spot on in terms of your ability to capture all the cross currents that were going on at that point. So. How did you learn so much and how did you get it? How did you get the nuances, which are so hard to do in a book? How'd you get the nuances? So right in such a readable Well, thank you so much. Uh, it's really wonderful to hear that it resonates.

Um, and I will say I worked on this book for what ended up being a very long time. The first paper that I wrote about this was in 2011 as a graduate student. Um, and I will say I think I really benefited from, uh, iterative conversations with some of the major players. So as I mentioned before, I met Velma Murphy Hill, uh, or I rather, I interviewed her by phone in 2006 as an undergraduate, uh, about a different protest about the Rainbow Beach Wades.

Uh, but then I was able to interview Velma multiple times to get to know her. Hear her speak on this history to UFT paras in 2014. Uh, get to know Norman as well. Uh, and many other people, uh, people who are on all different sides of these struggles. Uh, people from many different communities, racial, ethnic, religious, um, and one of the challenges for me was, of course there's a lot written and there are wonderful, wonderful archives.

The UFT and the a FT keep fantastic archives about this history. Uh, but in really wanting to understand how people felt, how people understood what they were doing at the time, I also wanted to conduct oral histories, and that too is a, it's a process. It can be slow. It was iterative. And I think what really helped was getting to know people and then being able to go back and forth between the stories I heard, the archival, uh, kind of piece and, and trying to make sense of it.

I'll also say I presented this all to a lot of different people. Um. Some people thought I got it wrong early on. I got a lot of very constructive critiques. Um, and in the end, what I really wanted to do as I, as I hope the book demonstrates, was really put the voices of paras and organizers front and center.

And as you, you said, you know, really trying to understand what happens in that initial campaign as the product of really, really organize, but also really sort of grassroots work, um, by paras to communicate with their communities about why it was so important that they have a union, that they be in this union, that they'd be able to have living wages and job security and a path to advancement.

And simultaneously to see teachers who worked with paras organizing to communicate that to the wider UFT. Certainly supportive by leadership, but in a way that I thought was really, um, just really remarkable. Right? And this is a sort of really successful organizing campaign against really difficult odds. And, uh, and it captured my attention early on and I just kept coming back to it.

there's a lot of strands about what you just said, why don't we talk about the Rainbow Beach, um, situation, because that's not in the book, but I think people would be actually interested in how Velma and Norman actually first met, and also how they, became such powerful organizers. so Velma, when she was 20, was involved with the NAACP Youth Council on the south side, uh, and. Through South side of Chicago. Yes. South side of Chicago. Exactly right. Not, not yet in New York.

And, uh, and she, through their organizing met Norman because he was, at that time with a Philip Randolph already organizing what they called the March on Conventions movement. The 1960 Republican National Convention was in Chicago. And so they met VMA tells a great story in a, in a film recently that was featured on Time Magazine's page, it's by a, a young filmmaker named Alex Hinton where she says, her, uh, her sister said something like, you've gotta meet this guy.

He, uh, he sounds like you, he sounds like a socialist. He sounds like an organizer. And they, they sort of got to know one another on picket lines. Those were their dates. Um, but then when they heard about. Black residents of Chicago being chased off of this beach, which was segregated, you know, not by law, but both by custom and by the way, police enforced or didn't, who is sort of comfortable there.

Uh, they decided they would wade in, in the spirit of the sit-ins in 1960, which of course had started February that year. Um, and they bravely did so they faced an unbelievable amount of hostility, uh, once a crowd gathered and they decided to leave, Velma was hit on the head with a rock. She needed 17 stitches. She suffered paralysis. Uh, and she was on the front page of the Chicago defender, and it was Norman.

It was other allies in Chicago who then publicized this event and really made it a citywide civil rights issue. And they came back to that beach to the rest of 1960 into 61. The one other connection I I wanted to make is to a Philip Randolph, because I do think when you think about the brotherhood of sleeping carports, right, there's no union that had a greater impact on a wider swath of social, uh.

And political organizing, you know, in the communities in which it was located and that union, right? If you look at the brotherhood, you see so many people who became civil rights organizers, who founded other unions, and of course a Philip Randolph understood organizing to be not just about the particular bread and butter games of individuals and locals, but about building a labor movement, right? That sustained people and communities.

And that's exactly the logic that Velma and Norman brought to the idea of organizing Paris. That's exactly what informed Velma, the idea that this was about not just giving individuals better wages. This was about building a kind of system that would empower communities, that would create paths to advancement.

Uh, and that would really sort of make good on some of the promises of the war on poverty, which had generated the funding for these positions, but hadn't really been realized to that point. It's in some ways, like a precursor of the fight for 15 and a union, um, where we, you know, where we got to. The fight for 15, but in so many ways didn't get to a union. so I wanna just get into a couple of nitty gritties.

I mean, I could spend hours talking to you, but I wanna get into a couple of nitty here, nitty, which is you, um, you talk about in the sixties, this kind of crisis of care. tell me what, um, you know, when you, when you think about crisis of care. What were, what did you hear? What were you, um, really framing in terms of that? And, and, and the reason that that struck out to me so much is these days we're thinking about a care crisis or a care economy.

And we're going back to language like that in terms of how we actually take care of families, not just inside of schools, but what do we do for childcare? What do we do for elder care? How do we make sure that domestic workers have, you know, real, you know, real conditions. So tell me a little bit about what you described as a crisis of care and, and why, uh, uh, teacher aides later called paraprofessionals were a quote solution to this. Absolutely.

this sort of crisis starts with just a crisis of numbers, right? This, the baby boom, you know, you see the near doubling of the US School going population from 1949 to 69, and there are so many children in classrooms, um, and in cities. This corresponds with a major demographic shift, right? So New York City sees its African American population more than double. Uh, it sees, uh, quadrupling of its, um, what was then called Hispanic population, mostly Puerto Rican, but not exclusively. Um, and.

So simultaneous to just needing more adults in classrooms. Uh, there are also real questions about how teachers, again, mostly white, um, mostly sort of, of a middle class persuasion by this point will connect to relate, to understand the particular challenges of folks who are recently arrived from the US south, from the Caribbean, other places as well.

And so, uh, the teacher aid idea actually starts as this administrative solution, which is about not hiring more teachers who of course are already starting to organize, but about filling a void. Much as you see today by stratifying a workforce. Right.

And the idea they used a study, uh, Ford Foundation did from Dow Chemical to break up the work of teaching and try to figure out exactly who, uh, could be up in front of a classroom and what things they could essentially, it didn't quite outsource, but Right. Devolve to a non-professional worker. Uh, you mean that wasn't taylorism? I, it's, it's taylorism, you're exactly, I think I even used that word in the book. A hundred percent. This is taylorism.

And, and so what happens of course is they hire these folks and just as has long been the case with teachers, there's a kind of gender language and expectation of a sort of devotion that people will do this not for money, and they're paid nothing but for, for love and because this is who they are. Um, and very quickly what becomes clear. As these folks enter the classroom, these age as they're called, one, they are doing educational work because they are working with children.

And because you can't actually break things apart so neatly, right? If you are working closely with a child, you are going to get to know them. You're also gonna bring the knowledge you have of their community into that classroom and share it with that teacher. And so even in the early fifties, we start to see teachers realizing that these folks are more than aids. We also start to see aids saying, one, we are doing something that matters and we can see that it matters.

And two, we would like a path to advancement too. Whether that means professionalizing the work we already do or eventually becoming teachers ourselves. And it's that kind of, um. Realization that I think generates a whole kind of world of bottom up organizing around what this work could be that really explicitly responds to the crisis of care, where you see organizers in Harlem and on the Lower East side, and these include some UFT members.

Richard Parrish, who actually was an a FT vice president at that point, found something called the Harlem Teachers Association. Um, mostly black but not all black teachers who work in Harlem, who work in the summer with parent age. Now they've changed the term, right? They're hiring parents and they create programs that are designed to address all kinds of things, right? They wanna get kids up to reading and, and, and, and, and numeracy levels.

But they also wanna make sure students feel comfortable in schools. They wanna bring parents into schools and make them comfortable in spaces that had been hostile to parents and to communities. Right? Right. And all of this work becomes then a very explicit address to that crisis of care. So that leads me to, because, 'cause I loved, I wanna just, uh, do one more of these terms, activist mothering. Explain how that became a very important strategy for paraprofessionals.

I just love that term, and I should say this, so I come to this term by way of the work of Annise Orick, uh, Nancy Naples, a sociologist, and they of course get it from Patricia Hill, Collins, bell Hooks Black Feminist Thinkers. Right? Right. You talk about other mothering community, other mothering, and the idea here being that in a world, and we should be clear in the sixties.

The mother, the, the working class mother, the black mother, the Puerto Rican mother, had been made a demonized figure by official social policy, right?

The fear of matriarchy in the black community, the work of Daniel Patrick Mohan and others that blamed often right motherhead households as kind of the root of problems in pathologies in these communities, which of course ignored all of the structural factors that were, that were shaping the, um, shaping the conditions people lived and worked under. And this term, of course, flips that on its head. And so many people, quite explicitly did.

People who became paras themselves had often been PTA presidents while working two jobs. Shelby Young Abrams, who became of course, uh, a UFT, uh, organized related chair of the para chapter was someone who talks about working in a chemical plant, working in a factory, working, uh, as a domestic, all while simultaneously raising her children, being involved in the PTA. And when the opportunity comes to go to work in these schools, people don't just take it, they cease it.

Uh, and what they do is they say, we are here. Not just as representatives of our children, but of the, the community's children who we know intimately who're gonna see on the street and in school and in, uh, churches and in, you know, uh, the halls of our buildings. And this kind of close, dense sort of social, uh, connection becomes really instrumental to the work. So many paras. Do you know another person on the Lower East Side?

Mary and Tom just passed away recently, rest for an incredible organizer who talked about how she would translate, right? Again, this seems obvious now, but she said she doubled the attendance at parent teacher conferences and at, you know, PTA meetings because she was just translating in Chinese at a time when many, many people on the lower East Side needed that.

And she also brought in knowledge about, you know, why is a student not wearing this shirt that we've made the uniform shirt, well, that looks like a funeral shirt in their part of China, right? That's one specific example. But that kind of local knowledge can make the difference between a student being marginalized or even disciplined and being understood, right? And so there's this very grassroots level work.

Uh, they can then, I think scale up people start to articulate, and this, I can go on, maybe I'll stop here so you can ask another question, but people start to, you know, from that kind of very detailed classroom level, school level, community level work, people start to articulate a wider vision that says, look, in fact, it's good that you hired us. And while you said, you know, oh, hiring mothers means you don't have to pay them anything.

And hiring mothers means they'll be docile and obedient. Quite the contrary, you have hired people who have deep connections to community, who understand their value and who have a lot of people behind them who are going to back them when they make demands for living wages and job security and the kinds of things that they really deserve. You are listening to the Labor Heritage Power Hour on WPFW 89.3 fm, your station for Jazz and Justice.

Back now to a FT President Randy Weingart's interview with Nick Ravich, author of Para Power, how Paraprofessional Labor Changed Education. I mean, it's kind of mind-boggling. We talk all the time about how schools should be closer to the communities in which they are located, how schools are the centers of community, how we need to make them safe and welcoming for our families.

And then there was all this back and forth at that moment about, oh no. We're gonna hire people from community, and God forbid we have to make it a living wage. I mean, the, the i I don't know if it's the hypocrisy, the irony or just, you know, when, when people then say and make these arguments, you know how they're, excuse me, full of sometimes instead of, actually, I don't know if I can say that on the radio. I hope I can, but, you know, somebody might bleep me out if I can't.

but it's just, it's so, um, what, what the para program did, is it, it was initially an empowerment program. First it was a, you know, A-A-A-A-A funding program, but then it became an empowerment program. And what's interesting, and you, you know, you saw this, I, I do wanna get into the civil rights issues in a minute, but. I wanted to ask this question first.

You saw in terms of the contracts for, forget for a moment about the organizing, but the contracts, and this was a really important question when I was president of the UFG as well, the vision was that we would create, uh, and fight for not just decent wages, not just social security, not just, you know, um, healthcare, not just, um, retirement security, all of which were things that were iterative in this contract, but a career ladder program,

um, where people would get release time to actually, um, become teachers. That was really important at that point. I want you to talk about why, but layered on that, when I was president of the UFT paraprofessionals and we had. We had a many member negotiating committee, and one of the things that Pariss wanted then and want now is a living wage for the work that they do. And in fact, the UFT right now is fighting for a $10,000 increase in wages for all para professionals.

Um, c um, Korea, uh, uh, Chicago Teachers Union in a contract they're about to finish, is doing the same thing. The work you were just up in Massachusetts, the work that Ed Markey is doing in terms of the push for living wage federally for paraprofessionals. And so it, what, what's starting to happen in this era? Is a question about whether automatically people want to go into teaching or whether they wanna actually have that job as a paraeducator and make it a living wage job.

And it, and it was interesting to read the book in terms of what, what, what the reasons were there for, why the career ladder was so important then and now, why a living wage is so important now. Absolutely. I do think it's also, it's, it sort of has to be both and Right, exactly.

One thing, one thing that was possible in the early seventies, we should say, because of the massive outpouring right, of organizing in New York City around this, what was possible was accessing a massive free growing system that had open admissions. Right. CUNY at that time is not, has moved to open admissions, and this means that there are newly available resources quite explicitly connected to the same set of ideas, right? We need to better serve the communities we're from.

We need not be exclusionary or elite anymore. We need to be open and reaching people and meeting people where they're at. Uh, LaGuardia Community College becomes the first to graduate paras from a para program. They actually have to have a graduation ceremony before they're even. You know, ready to have another one for anyone else because they start before the system actually takes off. And that's a great example of the kind of new parts of CUNY that are doing this work.

Um, and what I found that this, this was really important for a couple reasons. The career ladder was important in part because it didn't just mean people were going to work all the way to teacher. There were lots of steps along the way. And again, because Kuni was open admission, because there was not just release time, but paid stipended release time, people exactly. Move in and out a little more easily than you could now in a system that's much, much more tightly managed.

And that's higher ed. I should be clear. That's not, that's not really a union, uh, thing in some ways, but the, um. The opportunity that was there was much broader and open. And at the same time, it was still a very long path to become a teacher. Right? Paras, many of them came in, this was the law at the time, didn't have to have a high school diploma. And of course, they were coming from places where they'd been denied access to education, right?

But at the same time, working from there to, you know, a GED or an equivalence of another kind through a ba up to a teaching certificate, this could take six years. Um, people did it only a small percentage, but along the way, a great many people gained, you know, a bit of education.

They gained, you know, new salary lanes, new opportunities, and also they gained a. Degrees and skills and opportunities that become useful in their communities that could be useful if they left the profession went in another direction. Um, and the last thing I'll say about why this was so important at the time was that in addition, I think to affirming that paras were educators for paras and creating opportunities that they had been promised in the war on poverty, but that were not delivered.

Um, this was also really important rhetorically for shaping teachers' understanding of who paras were. Yeah. And I do think, you know, someone like David Selden relies on a really kind of, and again, he was, he was a FT president at the time, a kind of almost, this is something I learned from Dan Ner, a kind of. Mid-century sort of craft union model, right?

That, that, that unions should indeed control and have a say in this sort of training in the profession and help find ways to sort of guide people to this. I think for folks like, uh, like Velma and Norman, uh, this was also more of a kind of industrial union model, right? You get past that over divided workplace and you say everybody in this workplace is part of the same unit, should have opportunities to advance within it. Um, so this did a lot of work.

I think bringing teachers, some of whom were afraid were hostile to paras when they were first coming into schools and later the union brought them around and it created opportunities. Right. I will say, you know, I'll just, one last thing, talking to Clarence Taylor's a wonderful historian of education. He actually started as a para in New York. Um, that was Oh wow. Job in education. I interviewed him.

Uh, he Wow. When. After the fiscal crisis, the CUNY system breaks down and it breaks down almost overnight because CUNY starts charging tuition. The city doesn't have money to pay it for the paras. Um, UFT is not in any, had a position to bargain this. Their 75 strike, they're out for two weeks. And as people who let it remember, they would've left 'em out longer. It was saving the city money. It was not a, uh, a good bargaining position. And so, yeah.

Um, when this breaks down, Taylor worried that it could become a C, right? That, that you could have a model where it was, you're not paid well now, so go get your degree and then you will be, and that I think, is exactly what you're addressing here, right? We need to affirm that this work is educational work that deserves, you know, one, not just living wages, one job should be enough, right? That that was the cry of unite here all across the country a few years ago.

I think it's exactly applicable here, right? And in Boston, right, they just released a tentative agreement that's gonna see increases between 23 and 31% for Paris over the length of that contract. It's amazing. And so I think, um, I. Those kinds of demands are incredibly important at a baseline level. At the same time, I feel like any para who wants to become a teacher should have a paid and smooth path to doing so. Right. I can't think of anyone better.

And I do think it flies in the face of some of the, the neoliberal ed reforms we've seen over the last 20 years, right. That say, oh, you don't need any training to be a teacher, or All you need is an elite college, or a high SAT score, five week summer institute. Right? Uh, and I think when we flip that on its head and say, actually the people we know have been in these classrooms sometimes for decades, they've got the experience to be teachers.

It, it reaffirms, uh, what we already know about education. Right. And it's powerful rejoinder, um, to all of that stuff. Sorry, it was a lot. No, no, no, no. It's really, it's really important. It's really a lot. And in reading, I, you know, I'm very proud of these locals who are actually saying, okay, at this moment in time, we have to actually do a bigger increase for paraprofessionals. I know when we did.

Uh, you know, a step lane, you know, was pretty controversial, but we were like, no, the paraprofessionals deserve and need it, and you need to, you know, you know, so, so I'm very proud of the locals who were doing this work, and it does remind me of the, you know, work that some of us had done and our predecessors had done, you know, like Loretta Johnson, like Shelby, like others in terms of really trying to make the economic argument important too, and really important as well.

And so that gets me, I just wanna, actually, I wanna ask you a couple more questions, but, you know, we've done a lot of class questions. I wanna do some race questions too, which is essentially, um, people at that moment when the, when, when the paraprofessionals were being organized in New York City, there's a big debate about whether they went to. They had the choice about whether to go to Afme or to go to UFT. Um, and both unions very much pushed very hard.

Um, and by a small vote the Paris elected to go to UFT, but there was a lot of issues around whether or not they were, you know, there were a lot of, of issues around race at the time in the city of New York, and I'm sure that, you know, so, so what I'm asking you is you talked to a lot of people who were still, still alive right now, but in the midst of that and including two people who were the first organizers who took, took different sides on it.

So tell me your sense of why the paraprofessionals chose the UFT over afscme. And of course it was a very close vote. Uh, very close. We should, we should note that about, um, 3,800 paras of the 4,000 who were eligible in that initial bargaining unit voted so there was a high turnout too. Um, and I think it was a couple, uh, not even a couple hundred votes might have been like 52 even. Right. Um, should have that handy. But the, the thing I would say is twofold.

What is, and this is an important part of the story. Well, we think of the bulk of the campaign coming after Ocean Hill Brownsville, after that conflict, that split the union and, and really the sort of, um, by and large, the black and Puerto Rican community in the city. Uh, we also see before that some organizing.

So I wanna emphasize that organizing had started happening before Ocean Hill Brownsville with UFT, and that this organizing in particular had focused on paras and the teachers they worked with because initially. Paris weren't hired citywide because of the way war on poverty Funds were allocated because of the way the Board of Education process these things. Uh, they were clustered in the South Bronx, in central Brooklyn, in Harlem on the Lower East side.

And so what was clear was that you had an emerging grassroots solidarity even before Ocean Hill Brownsville. And I really think that's what sustains the possibility of Paris joining the UFT afterwards. Right? Because there is a great deal of hostility, right? There is a great deal of anger over the union's role and the ending of that community control experiment. Uh, there is an enormous amount of just vitriol and, um, fury. I always wanna highlight that. I think the people we should emphasize.

As sort of, um, getting this wrong in this story are also the city itself, which created a system and did not ever articulate as to who would be in charge and how it would work, and then when it blew up, absolutely dithered. Um, but I also wanna emphasize that there were very good reasons for many Paris. Some of them crossed picket lines during Ocean Hill.

Brownsville taught, had good experiences teaching, um, others of whom stayed out because they either were in solidarity with the teachers they worked with, or they were from union families. Many paras were really divided and really torn about this, what I think they felt. That one, they definitely needed a union, and two, that they needed an educator's union because they believed themselves to be educators. I really think that is the kind of core argument that carries the day.

And it's interesting when you talk to people and when you've, I've read through interviews some which were published in, you know, the Amsterdam news, the city's black paper, which had vociferously opposed the union, uh, during the 68 strikes, but also in, you know, the New York Times, other places, people say a range of things, but they're very clear that they're not belonging to the dynamic. Right.

I think one thing that happens is sometimes historians will either treat this as a vindication of the T'S leadership or they'll treat it as a kind of, you know, co-optation and that just erases the actual people who voted. And I think those people, some of them are very clear. Um, some said, there's one I remember of Para who, who told the, uh, the Baltimore African Americans, she said, I'm going to the highest bidder.

And what I take that to mean is I'm going where there's power, I'm going where we think we can win. Um, another person I interviewed said very simply, why the UFT they had clouted. Um, I also think that because the UFT emphasized the idea that paras would be. In classrooms and in the union, um, full members of the union, right? Uh, and not having in their own local that there would be an opportunity to build on what they had already done and to sort of address some of their concerns.

Now again, that happens differently in different locals and chapters. I don't wanna say it's some great easy path. Uh, but I do think the idea that Paris were educators, that they needed a strong union and that there was a, a possibility of building forward from this terrible and traumatic event, uh, informed the Paris who voted for the UFT. I wanna ask you, the question about, um, then it got to the seventies and the eighties and the nineties and the fiscal austerity.

And I think that the, um, what the, the, the shift from, you know, that, that the UFT also did, I think. In terms of, of, of being far more meaningful.

And look, we, I was UFT president from 1998 to 2009, and one of the most favorite things that I still keep with me after the fact was, um, several, um, op-eds that said that one of the things that happened was that we actually did, um, uh, heal some of the still lingering scars from Ocean Hill, which both Sandy Felman and I felt were very much part of what we had to do as union leaders. Um, and, um, but what, what we saw.

Seventies and the eighties, and you saw that as well, seventies, eighties, and nineties, was that initial neoliberal pushback. You know, when, when, when they, when people were like, oh, well this is not teacher work. This is mundane work, which it was not.

Then all of a sudden they started using that as a way of trying to fire, you know, thousands of thousands of paraprofessionals, particularly in the work that they were doing, you know, with low income kids as opposed to the work that they were doing with kids with disabilities. And so what, you know, what, what do you think happened between the empowerment moments of the fifties and the sixties and the austerity moments of the, you know, seventies, eighties, and nineties?

I. I mean, this is, this is a core question in the book, and I would say, you know, we see a, there's a number of sort of factors, the biggest of which are these fiscal crises of cities all around the country. And in New York, of course, it's 75, um, which give rise to a kind of radical rethinking of the urban social welfare state.

And, uh, Jane Berger has a really brilliant book about Baltimore actually, that talks about this, the way in which a kind of ascendant generation of urban Neos, right, and Koch in New York, others, um, link the people who need these services, the most working class people, uh, people of color, and the people who provide these services, who are also working class people.

And often, you know, black and Puerto Rican, often women right in the public sector, uh, link these folks to each other as undeserving. Right, right. And we see that with Ed Koch right away in New York, over the advice of his own school's chancellor who he brought on to start negotiating before he even entered Gracie Manchin. Koch says, I don't want the Paris to be on a 12 month contract. This is never about cost. Right? It's not the most expensive thing of the contract.

It's about carving out who's in and who's out in the neoliberal state. There's room for the professional, right? For the white middle class professional. There's not room for the working class, black or Puerto Rican mother, even though the work they're doing is just as essential because that whole realm, right, is what Koch and his cronies are. Delegitimizing, right? And because of this, we see a kind of.

You know, continued attack then that really does lead to, you know, a continued stratification in the workplaces. It's sort of the, the empire strikes back. It's the moment when that old vision from the Ford Foundation and the admins from the fifties comes back that says workplaces should be stratified, right? We're gonna promote, um, sort of elite teachers. We're gonna create sort of more paths to having these kind of highly professionalized roles in schools.

We're gonna hire lots more admins for that matter. Um, and the people who are sort of at the bottom of the ladder are going to fall behind in terms of their wage gains. They're gonna fall behind in terms of continuing to win access. The other thing we see is that the movements that have sustained paras, you know, are under attack. In the same era, right? The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Power Movement, they are under legal attack. They are under, you know, quite literal attack.

In the case of many black power leaders, um, the voice that had powered paras into schools is being silenced, you know, some cases by the state and some cases by changing political events. Um, that's true too, of, you know, the whole vision of a, of a new careers movement, a war on poverty. Uh, you know, this is being attacked by national politicians like Ronald Reagan. It's being attacked at the local level.

And, you know, I, I think of, you know, Randy, you are in the book, uh, that 2003 fight, uh, when Joel, Joel Klein tries to fire a whole bunch of paras. I know he's just warmed over. He's just returning to an old party. It was warm over. Yeah, but it's, but it's vicious because he's got, of course, mayoral control, which Kotch didn't have, and he's got a, um, he's got an ascendant at that point.

I mean, really a dominant neoliberal paradigm that says, right, this is not the group of workers who matter. This is not the model for education. We we're looking at charters and choice, and we're looking at, you know, educators who are, you know, fresh out of Ivy League schools, uh, and not thinking about any of those thick and right. Important community connections Paris have. That's not even in their model. No, not in their model. And we fought and I fought.

Um, and, and to your point, maybe this makes news. I never have said this publicly. I had a dinner with him before we sued, and based upon what he said, that suit was absolutely accurate and real. Um, the, the racism I had heard was shock. It shocked my conscience. And so, you know, and, and because I saw it that way exactly as you were saying, Nick. Absolutely. No, it's probably the last time I ever broke bread or had a meal with Joel Klein. Leave that too. Exactly. No, I think so.

I, you know, people are telling us that, people are telling me that we have spoken for well beyond 20 minutes. Of course, I could do this for well longer, but I, I guess I would ask you one last question, which is, what did I miss? I mean, this is a struggle. This, this is what the labor movement is. You actually, you know, and, and you actually find a way to collectively give people a voice. So they have a path and a voice for them. They themselves, collectively to get to their American dream.

And it was hugely important for the UFT. It's hugely important for the A FT. Um, what, what was done at that point? I would say that para organizing was almost in our, in our history was not as important, but almost as important as when we expelled our segregated locals. Because what we're saying is that. The path to unionization is multiracial, multicultural, um, uh, multi-ethnic. This is about all of us in America.

And I think that, that you, you know, that's what your book really talks about in terms of power, power, power. But let me ask you just last words in terms of what I should have asked, which I didn't. But I was really honored Nick, to have this conversation with you. Uh, likewise. And I, I would add, you know, to pick up on what you said. You know, we have, I think, an ascendant, uh, set of ideas in, in educator unionism today around social movement, unionism and bargaining for the common good.

That is exactly about that. Projecting the power of the labor movement beyond the, you know, the narrow confines of what are sometimes treated as, you know, bread and butter issues and saying, this is a movement for working people in the United States for our students and the communities they come from, as well as for our teachers, our paras, all of the people who work in our schools.

And I think there, you know, this is a really important point that, that paras articulated back then and still do, right? Which is that this all has to begin in our unions. Right? And it's true, as you said, it's challenging to say, we're gonna put, put these workers first because they've taken, you know, too little for too long, doing too much. But when we do, right, when they can go back to their communities and say, look, that, you know, that that rubber has hit the road.

There is, there is a. Commitment here to us and what we represent. Yeah. It's so powerful, right? And I think it, it's morally the right thing to do, but it's also strategically what we must do, especially in this moment, right? Because they're gonna be attacks. There are already attacks on teacher unions. They're the old ones that say, oh, they're only narrowly interested in themselves. They don't serve the kids. All this stuff.

We know this isn't true, but when we can show it isn't true because we have these powerful gains that you've mentioned already, uh, I think we've really, uh, we've done the right thing and we've done the smart thing. Thank you so much. Thank you. And the book is called, um, power. Power. And please, yep, there it is. Go read it, buy it, share it with others. Thank you. . Hi, this is Nick Juvi.

I teach history and labor studies at UMass Boston, and I'm a member of the faculty Staff Union of the Massachusetts Teachers Association. My favorite labor song always has been and always will be solidarity forever. But I wanna highlight a new one today, and that's all you Phonies, which is Woody Guthrie Lyrics set to Music by the Dropkick Murphy's. Uh, I love this one because it's got a great hook.

It reminds us that we need to know our history, and it celebrates a lesser known but radically important union. Of that 1930s era, the National Maritime Union or NMU, give it a listen. I'm Rick Smith, and this is Labor History. In Two, there are some songs that stand at the core of the labor movement year after year. These songs ring out on picket lines, at labor rallies, and in union halls across the world. These songs inspire and build solidarity between workers.

Undoubtedly, which side are you on? Is one of those songs on this day in labor history, the year was 1900. Today we celebrate the birthday of Florence Reese, the author of Which Side Are You On's, iconic Labor Lyrics. She was born in Tennessee, the daughter of a coal miner. During the 1930s, her husband Sam, was an organizer for the United Mine Workers in Harlan County, Kentucky in what came to be known as the Harlan County Wars. The Battle for Union recognition waged on for nearly a decade.

Often violence skirmishes broke out between striking miners and federal troops, and the mine owners hired guns. Legend has it that won fateful day in 1931. Deputies were dispatched to kill Sam Reap. He escaped just in the nick of time, but Florence and her children were terrorized as the deputies illegally searched and ransacked their home. When the deputies left an angry Florence ripped the calendar off the kitchen wall, and on it wrote the lyrics.

To which side are you on Folk Singer, Pete Seeger heard the song and in 1941, he recorded it with his group, the Almanac Singers. It entered into the lexicon of labor Anthems. Then in 1976, Florence appeared in the Oscar winning documentary, Harlan County, USA. The documentary told the story of a 1970s strike. In it, Florence sang her song and the lyrics provided a powerful addition to the film. Since then, many more artists.

Have covered versions of the song, including Annie DiFranco, Natalie Merchant, and this version by the drop kick. I just love that version. Wow. A double hit of the drop Kick Murphy's this week. Well, that's it for this week's edition of Labor History Today. You can subscribe to LHT on your favorite podcast app, even better. If you like what you hear, and we really hope you do, please like it in your podcast app. Pass it along, leave a review that really helps folks to find the show.

Labor History in Two is a partnership between the Illinois Labor History Society and the Rick Smith Show. That's a labor themed radio show out of Pennsylvania. Very special thanks this week to a FT President Randy Winegarten for so enthusiastically agreeing to interview Nick. You can catch Randy's own podcast, the AFT's Union Talk. That's Union, TALK, wherever you listen to podcasts.

Labor History today is produced by the Labor Heritage Foundation and the Cal Benefits Initiative for Labor and the working poor at Georgetown University. You can keep up with all the latest Labor arts news. Subscribe to the Labor Heritage Foundation's free Weekly newsletter at Labor Heritage. Dot org. The Labor History Today team includes Ben Blake, Patrick Dixon, Leon Fink, Sherry Lincoln, Joe McCarton, Evan Pap, Jessica Pak, and Alan AK for labor history today. This has been Chris Scarlet.

Thanks for listening. Keep banking history and we'll see you next time. Here's Florence Reese to take us out. Which side are you on? Which side are you on? Gentlemen, can you stand it or tell me how you can, will you be a gone thug or will you be a man? Which side are you on? Which side are you on? My daddy was a minor. He is now in the air and son, he'll be with you fellow work. He every battle on which side are you on or which side are you on?

Now all of you know which side you're on and they'll never keep us down.