I want to say I think it was their third Christmas. I think it spanned five Christmases that they were locked out, even though it was only a little over four years. And, um, Yeah, I just kept talking to people and asking them questions and listening and I played some union songs that I knew some of the old songs from the movement and played some non union songs, you know, just like just entertaining the workers there and the union hall was open kind of 24 7.

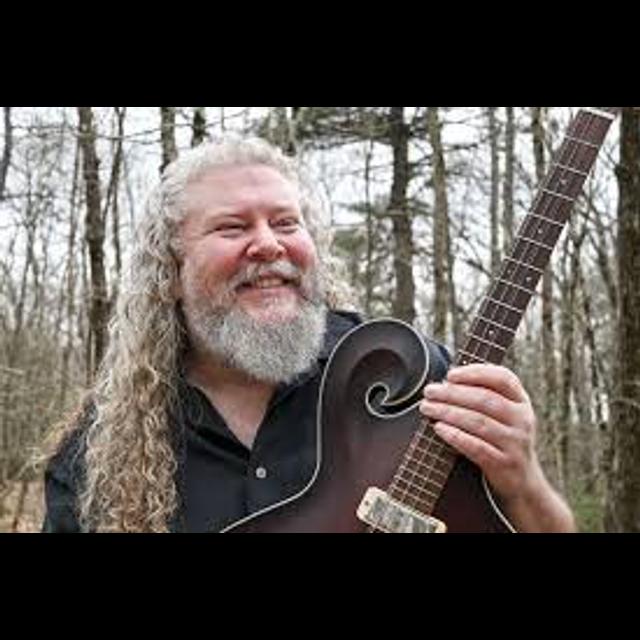

Um, because they knew that people needed a place to be. Joe GenX is a 25 year veteran of the international folk circuit and award winning songwriter and a celebrated vocalist based in Chicago. Merging conservatory training with his Irish roots and working class upbringing. Joe delivers engaged musical narrative sowed with heart, soul groove and grit. Pete Seeger said. The spirit of folk music is people working together. Joe is a fantastic singer who carries on the traditions.

Today, Joe tells us a story behind his song. Christmas in Mansfield. Where Armco locked out. 620 steelworkers on September 1st. 1999. I'm Chris Garlock. And this. His labor history today. Here's Joe Jenks with a story behind his song. Christmas in Mansfield. I moved to Cleveland in the fall of 2001. And I started connecting with the labor movement there, which was really different than the labor movement I had been connected to in Seattle at the time. Um, Seattle has a long fighting history.

I mean, you go back to the, the Everett Massacre, uh, in, you know, 19 15, 1917. Uh, you know, you look at the work of the Wobblies out there. You look at the general strike that happened in, in conjunction with the general strike in Winnipeg in 1919. Um, you know, there was a long fighting history in Seattle, but it was a really different flavor of union organizing out there. And then I moved to Cleveland. And there was just this really old school industrial organizing base.

And there were a lot of people that were really committed to the work and committed to labor rights as a part of civil rights.

And it was a really good community for me to land in in my late 20s and to be steeped in because it was, it's not that it was, you know, as opposed to the labor community in Seattle, it was just in addition to, it was, it was a different, it was And I got to know a lot of people that were connected, uh, as I mentioned in our last conversation to, uh, the Ohio Association of Public School Employees and, uh, a strike out in Ashtabula County that I wrote a song for called Rises One.

Uh, and through that community, I ended up meeting a felon named Bruce Bostick. Uh, and he got me down to Mansfield, Ohio. There was a lockout at a mill down there that was owned by AK Steel. And the workers had been locked out for a couple of years when I first met them. And Bruce was trying to get me to go down there for like nine months. And I kept being busy on the road and he'd call and say, Hey, you know, can we schedule something?

And it was either too short of notice or he wanted to schedule it for a time when I was out doing concerts. And then he called me one day and he said, where are you? I said, I'm home. He said, do you have any plans tonight? I said, no. He said, can I come over? I said, sure. So he comes over and he says, hop in my truck. We're going to man's field. And don't tell me you got something planned. Cause he already told me you were free the entire night.

So down to Mansfield, we went, which is, I don't know, two and a half hour drive, you know, south of Cleveland. Um, and I brought a guitar and we went into the union hall and I just started talking to the workers there. He sent word ahead to some of the, uh. The people he knew in the local that he was bringing a musician down who wanted to talk to some of the people who were locked out of the mill that they had been working at, some of them, most of their adult lives.

And I got stories of people who'd spent 17 years working there. You know, it was the only real job they'd had in their adult life. They came up as apprentices and then became journeymen in the union. And they worked at that mill. Uh, it was a mill that was profitable, a stainless steel rolling mill.

And, uh, you know, they, they were being locked out because AK Steel really wanted to, I think, and what seemed to be the case, as was later discovered, is that AK Steel was looking for a place to lose money. And they decided, AK Steel, that this mill in Mansfield, Ohio, was going to be that place.

Because if they spent You know, just Boku dollars on, you know, fighting the union there, then they could claim this huge loss, but the mill was profitable before the lockout, and it was profitable after the lockout, and the whole thing seemed very strange. They spent a lot of money to keep union workers out of the mill. They hired replacement workers, often known as scabs in the labor movement. Um, And, and the workers just held on and they were committed. I met one woman who was, I think 60.

seven at the time that I met her, she was going to retire at 66 or maybe 67 as the oldest female steelworker in the history of United Steelworkers. And, uh, she was determined to still claim that designation. And I think it was about four and a half years that they were locked out. And she went back to work for about a month, maybe six weeks after they resolved that, just because that was a thing that carried her through that whole period of time.

Knowing that somewhere on the end of this, she could claim that designation to retire as the oldest female steelworker in the history of the Union. So, this was the kind of determination that I encountered when I went down to Mansfield that one night. I just, it was, it was in the fall, and they were headed into, I think, maybe their third Christmas? Maybe it was just their second Christmas. I'd have to do some research to look up the dates.

But anyways, they, they, they were I want to say I think it was their third Christmas. I think it spanned five Christmases that they were locked out, even though it was only a little over four years. And, um, Yeah, I just kept talking to people and asking them questions and listening and I played some union songs that I knew some of the old songs from the movement and played some non union songs, you know, just like just entertaining the workers there and the union hall was open kind of 24 7.

Um, because they knew that people needed a place to be. There were second shift and third shift workers that, that didn't have a job to go to and they needed a place to be. Sometimes, you know, because home was hard with, without being employed. And so they'd come in and, and um, you know, they'd have different activities going there and they were trying to help find, you know, day jobs for people and odd jobs for people here and there. And the union was working pretty hard.

But they, they spread word throughout. Uh, the Ohio River Valley and throughout the United Steelworkers across North America and into other unions that they really needed support. And, um, yeah, it was very moving to me. It was very moving to me that, uh, you know, so many people in so many places gave money to their strike fund, um, in essence. And they weren't on strike, to be clear. They were locked out. The workers were willing to work.

Uh, but the company had locked them out and said they would not allow union workers into the mill. And, in retrospect, the whole thing seems like it was for nothing. You know, I mean, it galvanized the labor community there, and it galvanized the steel workers, um, no pun intended. Uh, you know, it really had people fired up, but from the standpoint of what did AK Steel accomplish by doing this, I don't think they accomplished anything.

I think they intentionally lost a lot of money, and they disrupted the lives of hundreds and hundreds of people in order to do it. But there seems to be no real tactic or strategy intended behind it other than, you know, general union busting and losing money so they would pay less taxes. But, you know, you would think they would pick a mill that was losing money rather than a mill that was making money.

Um, you know, so the, the, the whole thing was a little odd, but as I, as I interviewed people that night that Bruce Bostic brought me down there, as I had conversations with people, I started winding into a story that felt incredibly familiar To me, um, my father, um, though he was fairly anti union in principle when I was growing up, he was very much in solidarity with other workers. It was an interesting contradiction.

And so I remember as a child, there was a strike at a place where he worked and his job was not unionized within that company, but he didn't want to be seen to be crossing a picket line, even though he wasn't particularly pro union. He was wanting to be in solidarity with his fellow workers. And so he would get up really early and go to work before they set up the picket line.

And he would stay late and leave after they had all gone home, so that nobody would see him crossing a picket line, and he wouldn't, um, you know, in any way validate the company's perspective over that of the workers. Hey, it's Chris. And you're listening to labor history today brought to you by the labor heritage foundation, which works to preserve labor culture and history. If you want to support our work, please consider contributing to LHF it's tax deductible.

And right now all contributions are being matched. So your contribution goes twice as far. Go to labor heritage.org and click on double your donation. Thank you. Now, back to my interview with Joe Jenks. My folks had seven kids and times were pretty lean, particularly in my younger years. And so as I'm in the steel hall hearing workers talk about How they were getting through the holidays and, you know, wanting support from the community.

John McCutcheon wrote in a song about homelessness once, uh, a line that always stayed with me. Uh, I'm not looking for a handout, but I sure could use a hand. And, uh, that's the spirit that I met. I met people who were hardworking, really engaged human beings, who just wanted the opportunity to do the work that they had been doing.

And so they organized, and the Women of Steel, which is sort of like a benevolent organization within United Steelworkers, organized these events, uh, to help rally support for the workers and for their families.

And, uh, I was very moved by hearing stories about what they did at Christmastime and that the, uh, you know, the fireman's union from down in Cincinnati and Dayton and Columbus would take up collections and they'd show up with turkeys and hams and another, you know, Set a union folks from another sector of the the union world would do a toy drive and bring toys in for the kids And you know They they would just do all these things to make sure that

at least through the holidays that these families really had some good support And I heard somebody tell me a story about Do an odd job so that he had enough money to go buy what was the equivalent of a Charlie Brown tree for his family, you know, just the most ragtaggle tree left on the lot and put up the lights that the family had always used every Christmas.

The old, you know, big bulb screw in the socket kind of Christmas lights and, um, I just, uh, it, it, it broke my heart and it lifted me up at the same time to be witness to their story. And so I wrote the song Christmas in Mansfield directly from things that had been said to me by the workers in the hall.

And I put it out there and, uh, the women of steel asked me specifically to start coming to various events and rallies and playing, uh, for some of these things they were doing in various union halls. Around the state of Ohio, uh, as they were trying to raise money, uh, to help support the workers in Mansfield and it, you know, after all of this had been playing out for about a year, maybe a year and a half, I had gone down. I think 2 different Christmases to sing that song for the workers.

There was a big rally down in Mansfield and they told me that. Uh, Dolores Huerta was going to be there. I think she was vice, vice president of the AFL CIO at the time.

And Dennis Kucinich was there, and um, Sherrod Brown was going to be there, and you know, there were going to be a bunch of dignitaries, and there were going to be like four or five thousand steelworkers from all over Ohio and parts of Canada and Pennsylvania and Indiana, Northern Kentucky, and they were all coming together to show solidarity for these workers. And they asked me to come sing. So I was all prepared to sing.

And then right at the last minute, um, my buddy Bruce Bostic says, Oh yeah, they're going to want you to sing the national anthem too. And this is like, like literally less than a minute before this whole rally kicked off. And I think there's a, uh, more of a swing and trade unionism now where a lot more trade unionists and union workers would identify as being democratic party members, or at least.

You know, in alignment with some Democratic Party values, go back 22 years, and there were a lot of Republican steelworkers who were a part of the union. And so, a lot of them were military veterans, you know, like, this is not a crew you want to screw up the national anthem in front of. And I used to sing the national anthem all the time when I was in college.

I used to sing for hockey games and football games and all kinds of things, but I had not sung the national anthem in probably 8 or 10 years. Outside of going to the occasional ball game and, you know, you know, humming along with the rest of the stadium, you know, so all of a sudden they're just handed me a microphone in front of all these politicians and, you know, nationally, internationally recognized union leaders that, you know, 5000 fired up steel workers.

the National Anthem and pray to God that I don't screw it up. And it came off great. It was one of the most terrifying moments of my professional career. Uh, but it turned out really well. And that song became an anthem for people in the steel workers. union, not just the people in Mansfield. It spread kind of virally, uh, movement in that time.

And I gave them permission to reproduce it and share it and, you know, just freely distribute the song we're able because it seemed like a good organizing tool for them at the time. Uh, and even still, I play that song a lot during the holidays and, um, People are really moved by the story. The fourth verse is taken from something that I witnessed. It says, Daddy looked down at his children and he smiled with sorrow and pride.

Daddy looked down at his children And he smiled with sorrow and pride Then he sat down on the union hall floor Put his face in his hands, and he started to cry. Though he had been strong now for years, He just couldn't hold back the tears. God bless these workers and families, For the road that they travel is long. And as they stand up for what they believe, God grant them courage.

Let the spirit of hope still shine bright As the stars down on Mansfield that night And, you know, in a way, I was sort of quoting the cadence of Merry Christmas to all and to all a good night. But there's also all this imagery, certainly in the Christian traditions, of the Christmas star shining down on Bethlehem. It just, it felt like there were moments of genuine grace and extraordinary kindness and mercy that I witnessed.

in that community and in that union hall as people rallied to support the families of over 400 steelworkers that were locked out. And it really was my honor to just bear witness to some small piece of their story and song and hand to them. Uh, a narrative ballad that became a bit of an anthem for them in that time. And I learned a lot about the very pragmatic side of labor organizing.

You know, there's, we have these notions in our, in our head of these very Weirdly, I would say almost glamorous sort of people that, you know, like, went into the coalfields and, you know, went into the mills and righteously organized people. But there's another side to this, which is how do you keep people holding faith in the value of being a part of a union when it's costing them a job?

If they left the union, if they chose not to stay in solidarity with their fellow union workers and cross that picket line and go into that workplace and take a job to feed their family, how do you tell somebody, no, you, you have to hold fast, even though you have mouths to feed? You can't give in because we have to stand together if we want to get anything done.

And part of how you do that is through a lot of internal organizing and groups like Women of Steel and having a union like United Steelworkers that represents workers in the United States and in Canada. And so you have a broad enough base.

that you can send out the collection plate and tell people throughout your union, these workers in this place, in this specific time, need our support, because the work that they are doing, what they are enduring, the struggle and the suffering that they are moving through, is something that is on behalf of all of us.

It's not just about one mill in one town and this set of workers, if we collectively hold the line with them and make sure that they have the financial support that they need, then we can prevail there. And we make it so that people in that industry or perhaps even in other industries think differently about choosing to push workers into that circumstance because they analyze it and go, God, that was a colossal waste of money and time and nothing was accomplished. But the sense of solidarity.

Has to be beyond, this is where I live, this is my union local, this is my particular struggle. That sense of solidarity has to be within a whole movement. It's, you know, it's why I talk about the labor movement and why I think so many cultural workers within the movement talk about the movement as a whole, not just one union or one specific struggle.

Because there's no way any of us can endure the things that we need to and hold the line for our fellow workers and for ourselves if we don't see that there is a whole movement that has our back, you know. And I think a lot of the workers in Mansfield understood that for the first time. You know, when that strike happened, not strike, when that lockout occurred and they began to realize that they had a union and family that spanned an entire continent.

It was a very different circumstance for them. Um, you know, yeah, it's, there, there was a sense of, of, there was a sense of hopelessness when I walked in that night. And when they found out I was going to write a song about their story, there was some hope. And when I delivered a song about their story, that became real. And it was one more affirmation to them that, that there was a community of people that cared about their well being. That they were not alone.

And, uh, I was by no means the first or the last person to affirm that for them. But it's part of the reason why I think songs really have a critical place in the labor movement, because it's a very unique kind of solidarity that we show through music and through art for our fellow workers. And we get to affirm for them in a very tangible way, something that they can hang on to, uh, and sing to themselves. You know, that people are thinking about them.

And I think that connection to hope and an awareness that there are other people that are committed to their well being, even if they don't see them, I think that has an impact. Um, uh, I want to read another little piece of lyric from this. Um, It's Christmas once more down in Mansfield And there isn't even much snow And nobody's counting on charity It seems that was used up a long time ago But somewhere Dad found a small tree And he hung up the lights carefully.

And the women of steel from the steel workers union brought toys for the girls and the boys. The fireman's union from somewhere downstate brought turkeys and hams, and they filled up the plate with cheers and good tidings for all. It's Christmas in a steel union hall. And it really was a festival spirit, and the weight that people were holding onto, that they were carrying, was lifted, if only for one night. And, uh, yeah, it's like nothing I'd ever seen before in my life, before or since.

It really was an extraordinary thing, to see how many people from how many different places across North America, were sending money and other tangible forms of support to the workers in Mansfield, Ohio, so that they could endure through this lockout however long it took to get another union contract in place and hold the line for workers everywhere.

It really was just a remarkable thing to see, and I would wish that the value of dedicated union workers was more obvious to the companies in the first place. You know, this didn't have to happen. You know, they could have just gone to the bargaining table and worked out a new contract and that would have been fine. But somebody got a thorn in their side that they were going to stick it to the union. And in the end, they lost. The union prevailed.

But it, it caused a lot of hardship to a lot of people. And that's the thing that's hard for me to wrap my head around. Like, you know, why wouldn't you want to treat people fairly? Why wouldn't you want to treat people reasonably? And, uh, I guess that is perhaps more of a working person's ethos around these things. But, um, yeah. It was hard for me to comprehend what the, what the strategic value was in trying to stick it to those workers. Uh, because they didn't break the union.

They didn't even break that local, you know? They just caused a lot of pain to a lot of people for a long period of time. But in so doing, they Sort of reawakened a spirit within the steel workers union and within the trade union movement, uh, certainly in the Midwest, um, such that people really began to understand differently. This is why we organize. Because if we don't, this is the power that's just gonna steam up. So, we're gonna stand up.

And, um, it was just, like I say, an immense privilege to bear witness to that story and document some piece of it and solve. Joe GenX with the story behind his song, Christmas in Mansfield. Here on labor history today. LHT is brought to you by the labor heritage foundation, which works to preserve labor culture and history. If you'd like to support our work, please consider contributing to LHF it's tax deductible. And right now all contributions are being met.

So your contribution goes twice as far. Go to labor heritage.org and click on double your donation. And that's it for this week's edition of labor history today, you can subscribe to L H T on your favorite podcast app, even better if you like what you hear and we sure hope you do like it in your podcast app, pass it along, leave a review that really helps folks to find the show.

Labor history Z is produced by the labor heritage foundation and the Kalmanovitz initiative for labor and the working poor at Georgetown university. You can keep up with all the latest labor arts news subscribed to the labor heritage foundations, a weekly [email protected]. For labor history today, this has been Chris Garlock. Thanks for listening. Keep making history. And we'll see you next time.