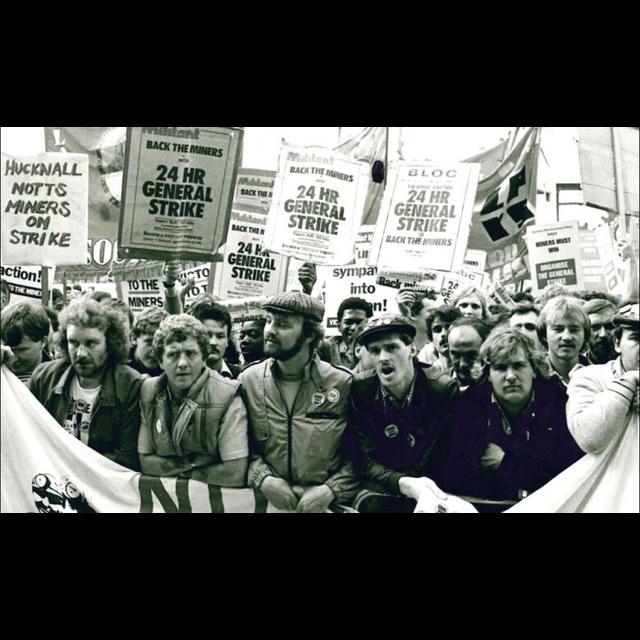

And then I felt my head explode and, uh. I didn't know what had happened. And uh, it is just like in films when you, you've, you've been hit or around the head, the, the world turns into slow motion and everything seemed to go black and white. That was John Dunn being interviewed by Tino Skai on the Heartland Labor Forum, KKFI 90.1 in Kansas surgery 40 years ago this year in March, 1985, the year long strike of the National Union of Mine workers ended in Great Britain.

The minor strike was about jobs, a protest against pit closures and the preservation of mining communities, but it evolved into much more than that. While Margaret Thatcher's government proposed the closures in the name of progress and modernity, buoyed by discoveries of oil in the North Sea and claiming that many pits have become obsolete and productive and too expensive to operate, Maddy would argue.

That the confrontation that ensued was more about the power of the state to break the back of one of the country's strongest unions and transition to an international energy market, which was beyond Labor's power. Indeed, decades later, until as recently as 2024, great Britain continued to operate Coal Pot Great Britain continue to operate coal fired power plants using I import coal in this episode of labor history today.

Former minor, John Dunn tells his story revealing some of the violent measures the Thatcher government was willing to employ in order to win the strike. We have labor history in two from Rick Smith in the Illinois Labor History, society, and Music from the Oyster Band Performing Coal Knot Doll, a poem written by Kay Sutcliffe. Who was the wife of a Kent Coal miner? She penned the poem during the minor strike in 1984. I'm Rick Smith, and this is labor History.

In two this day in labor history, the year was 1886. That evening, a workers' rally in Chicago, Illinois became known as the haymarket tragedy on May 1st. Workers across the city and around the country held massive rallies. For the eight hour workday, two days later, the police had fired into a crowd of workers on strike outside the McCormick Reaper plant in the Chicago neighborhood of Pilsen.

Two workers were slain and many more were injured, angry workers called a rally at the city's Haymarket square to protest the police violence and to call for the eight hour day. When the police attempted to disband the rally as it was ending, an unknown person threw a dynamite bomb into the ranks of the advancing police. In their confusion, the police began firing their weapons.

A total of seven policemen were killed and an unknown number of workers were struck in the aftermath of the bombing union offices and labor papers were rated throughout the city. Eight vocal supporters of the workers' movement were put on trial. Four of the men, Albert Parsons, August spies, George Engel and Adolf Fisher were sentenced to death by hanging a fifth man, Lewis Ling died under mysterious circumstances in prison.

Historian Bill Edelman explained the importance of Haymarket saying no single event has influenced the history of labor in Illinois, the United States, and even the world. More than the Haymarket affair. It began with a rally on May 4th, 1886, but the consequences are still being felt today. Although the rally is included in American history textbooks. Very few present the event accurately or point out its significance throughout the world.

The Haymarket martyrs are remembered and Mayday is celebrated as International Workers' Day. Labor history and two, brought to you by the Illinois Labor History Society and the Rick Smith Show. I'm Tina Skai and you're listening to the Heartland Labor Forum. On tonight's show, we're bringing you on an enlightening journey through one of the most defining moments in British industrial history. The British minor strike, as told by one of its survivors, John Dunn.

Mr. Dunn will take us all back to one spring morning in 1984 that changed his life forever. A time when miners across the UK took a stand against the National Coal Trust, Margaret Thatcher, and that neoliberal anti-union policies that threatened the livelihoods and the very unions that protected workers across the entire western world.

Through John's recollection, we will explore the courage and resilience of the miners, their communities, and the impact of their struggle on the nation's economy, politics, and social fabric. In his firsthand account and historical perspective that paints a vivid picture of the strikes, origins, its key players, and the profound consequences it had on British society and society around the world.

Join us as we uncover the stories behind the headlines, the personal sacrifices made and the lasting legacy of the British Minor strike. Whether or not you're familiar with this chapter of history or discovering it for the first time, this program promises to offer compelling narratives and thought provoking discussions that highlight the significance of the minors fight for justice.

And for the first time with our Kansas City audience, Mr. John Dunn, well ju 41 years and one month ago my union, the National Union and mine workers in embark on a year long strike. Not for wages, not for better conditions, but purely to keep our jobs. We, there was a hit list. The government said they were gonna close 20 pits. We knew that there were a whole scale slaughter. Of our industry.

And so, uh, one by one different areas of our union joined in strike action until by mid-March the strike was relatively solid and, uh, achieving its goals. And then we now know that Margaret Thatcher, uh, has, has been documented well in her cabinet. Papers that are now released issued an order to the police and the courts that they've gotta get tough. We striking miners and so we saw. State repression like no one could ever have imagined.

We had roadblocks, we couldn't travel out of our villages. The Nottingham that had continued working were, were surrounded by thousands and thousands of police to protect scabs, uh, and violence that was un unleashed, had had never ever been seen on mainland of of Britain. We'd actually got, we've now found a paramilitary trained police force, and I was a very early victim of, uh, of that, uh, state violence. We, on April the ninth, just over 41 years ago, uh.

I were on a very peaceful picket at Crest wool collar it, where the majority of miners were, were still working up to that point. I should add, we'd been relatively successful in starting to picket nottinghamshire, uh, the Nottinghamshire area had a history going back to general strikers, a strike breaking. Um, but we'd, we'd had tremendous success in a rolling picketing program and getting pits out one by one. And it was because of that success that the iron hand of the state came down.

They had to keep at least the Nottingham Coalfield working. So, as I say, on April the ninth, peaceful picket, uh, it was, uh, early evening, uh, uh, we, the picket was dispersing and I was walking back to, to get my ride home with, uh, with my colleagues. Uh, I saw a young lad square fighting actually with a police inspector. So I grabbed him and shoved him back in picket line, more or less, telling him not to be so stupid. And then I felt my head explode and, uh.

I didn't know what had happened. And uh, it is just like in films when you, you've, you've been hit or around the head, the, the world turns into slow motion and everything seemed to go black and white. And what lick, lack and remember is I was struggling to stay on my feet. And I turned around and I saw this policeman absolutely drenched in blood. And I didn't realize at the time it were my blood. It, it trench in the back of my head. Uh, that's important to remember the back of my head.

I wasn't facing him. As I said, I was walking away and the next thing I could hear was somebody screaming, take him, take him, take him. And two coppers dragged me. And, uh, I could Adley walk and took and dragged me across the, uh, the cricket field we're actually in that belonged to mine and, uh, put me in a police van with other people who've been arrested. And, uh, I, uh, I was put in the back and I felt something warm on the back of my neck and I didn't know what it were.

And I, I touched it and my hand came away, covered in blood. It was pouring outta my head. It had actually run down me back and gone into me jeans and I was, I was soaked through. So I alerted the police sergeant who was in charge. Uh, of this van. And, uh, he said, oh, we'll, we'll take you into the pit ambulance room. Every pit had a, uh, had an ambulance room. 'cause obviously there were lots of injuries in mine. And I just said, I don't want scabs touching me.

And so I'm, I'm, I'm afraid I'm gonna have to swear here a little bit. But his very kind words to me then was, well, you can bleed to death then. And they left me, uh, semi-conscious in the back of this wagon, uh, with blood pouring outta my head. Now my, my late brother. Uh, he was a branch, official branch delegate to nearby Pete to mine and heard what had happened and turned up. Now, me brother, were a big lad and shall we say, he had a bit of a presence about him.

And when he asked this copper what was happening with me, this copper laughed at him. So my brother, in, in a way that I can't quite mimic, just said, I don't find that funny. Uh, and obviously the copper felt a little bit intimidated. Uh, and I'm sure if my brother had had to bless him, he would've ripped the doors off that wagon and fetch me out if he'd had to. So the police called an ambulance. And they took me to, uh, uh, casualty department in a, in a hospital at Chesterfield.

And when I got there, I was sur was, I was surrounded by eight plain clothes police officers. Now, I should say, as, as at the time, I was quite a prominent local counselor. So they, they must have, uh, discovered who I aware and found out I perhaps had an outlet to expose this. So they, they surrounded the police surgeon and he, he was so intimidated. He sold me up without anesthetic, which I can tell you John hurts a little bit.

And his hand was shaking and it didn't, he didn't even seal the wound. So after that, he then, uh. Took me and put me in a police cell, my then wife, then we had a friend who was a doctor, and she called him out and insisted he be allowed to examine me. And he examined me and I, I wasn't sure what was happening. Nothing made any sense in the sort of state I was in. And he, he, he said to the police, uh, in charge, he's got a severe concussion, he must be in hospital under constant observation.

So after he left, they then called in a, the, the, the official police doctor who said, yes, he's got severe concussion, and gave me two aspirin. And he needs constant observation. And the constant observation took the form of banging on my cell door. Every 20 minutes or half an hour saying, are you still alive in there? So the next day still covered in blood. I was taken to, to the local magistrate's court and then I found out I'd been charged with threatening behavior.

Now, remember the back of my head. So I obviously threatened this policeman in his tranum with the back of my head. He must have found it somewhat intimidating. So I was then, uh, put on, uh, no chance to defend myself. It was just an automatic process. As I say, uh, Thatcher had instructed the police and the courts. They got a speed up how they dealt with us. So I was put on police bail, which prevented me from going anywhere near. National Coal Board's properties.

So it effectively stopped people picketing. And this was a tactic they used throughout the strike to take people off the picket line. And, uh, I remember, I, I went home and, uh, I, uh, my family had not known when I was going to get home. Pickets would be in jailed, uh, for similar things. And, uh, so I went home and then a, a day or two later while I was still recovering, I got asked by my area, the National Union of Mine workers was an area, uh. Formation of a union.

The ish area then said, would I be prepared to take out, uh, a private summons so we could expose nationally the sort of violence that was happening? So I did in my name, they took out three private prosecutions, one against the policeman who'd attacked me, uh, the chief constable of, uh, Nottinghamshire, which was the police force in charge, and the Chief Constable Derby should, uh, which is where the, uh, the mine was situated.

So I took out three private prosecutions and, uh, uh, I didn't go back on picket line 'cause they didn't wanna prejudice. Uh. My, uh, my case and lose these prosecution. I was examined privately by a doctor who said I'd been hit, uh, by a, uh, a spherical shaped, elongated, uh, object, which obviously a police trun or a baton. And, uh, and so, uh, I was, I actually went round the country speaking and rallying support in September that year.

I appeared in, in, in a, a so-called magistrates call, but what they did is they created special courts to deal with striking minors, and they put people in charge of 'em that they called stipend magistrates. Well, these were retired judges, so there's only one, there's only one judge here in your trial. And actually. In, they opened up a courthouse that had been, uh, closed for three years just to try minors.

On the day of my so-called trial, uh, a man I always remember I sat with my solicitor and, uh, another fella came up and handed me a piece of paper and said, this is for you Mr. Dunn. And I found on reading it, this is literally two minutes before I appeared in court, that it was a second charge, uh, of watching them be setting, which it's an, what the hell is an act? It's an act that dates back from the 16 hundreds. It predates trade union. It literally means.

Well, watching means looking at people. So I find me, and we didn't have time to discuss this before I went into court. It's quite funny now I can have a good laugh at it, but, uh, so I'd obviously been charged not just with threatening this police drunken with the back of my head, but looking at it with the back of my head. Now, I know in inside the labor movement at times you need eyes in the back of the back of your head. Well, that's carrying it, I think, to ludicrous extremes.

Now, normally when you appeared in front of these retired judges, you were wield in, found guilty and sent out. And there were loads of minors being processed that day. You can't call it a trial. Uh, but I was the only one who had any police witnesses against me. 'cause they had to make sure that these private prosecutions died. So, uh, one after one, they came in and I'm sorry if it's an elongated story. No, you do. It shaped my life then.

And since the first police witness, who I'd never seen before, by the way, had only set eyes on the copper, who, uh, who attacked me, said he, he recognized me. I, I had long and my hair was a different shade of blonde, shall we say in those days. Uh, and he said he could recognize me by my long flowing locks because it was well illuminated, uh, in the pit flood lines.

So my barrister pointed out that even according to police records, the, the, uh, the flood lights have been put out an hour before I was attacked. So he goes out and number two comes in and he is obviously been told, don't mention the flood lights. So he says, even though it was quite dark, I could recognize Mr. Dunn by his long flowing lofts. They all remembered that. Uh, and uh, and also he was wearing a combat jacket.

So then we produced this little black bomber jacket had been wearing and no camouflage on it at all. Uh, and, uh, it was still covered in my blood and the prosecution solicitor refused to handle it in case he caught a disease from it. He, I think he thought he might have become a trade, only a militant. So one by one, they all came in and told the story about how they could recognize me. Uh, after the second one, nobody mentioned the camouflage combat jacket ever again.

Uh, and the last witness said, yes, I remember him very well. He was stood at the front of the picket line. Remember, we were, we were leaving the picket. There was no front of the, and Mr. Dawn, I recognized him again by my long flowing locks, and he turned round and shouted to his fellow pickets, let's get them chaps. Now, I don't know any minor who use that sort of language, let alone refer to anybody as chaps. So, uh, and, and that's, I I often wondered if I'd, if I'd sort of in my, uh.

S fu stated and Miss Air this. But then I spoke at a meeting a couple of years ago and another arrested picket. They had been alleged to say the same thing. We obviously spoke very polite on the picket line and when we were incited people. So anyway, uh, very well behaved. You all are. That's it. Yeah. So the judge in summing up said he believed everything I said, but he said, Mr. Dun got carried away and uttered those words. Let's get them chaps. So, uh, that was it. I was found guilty.

The private prosecutions collapsed, and, uh, I've still got a criminal record to this day for watching them be dissecting and the threatening behavior. Now, they don't normally bother me, but. During the strike I made, I made a lifelong friend who now lives in New York, and in 2018, I wanted to go and visit her. Uh, and I got denied a visa, presumably because of my criminal record. So, uh, I mean, it might be a blessing now that Mr. Trump's in power, but I wouldn't want to visit.

So that's my bizarre story, but I'm not unique in that. You know, the, the most famous thing about that strike was the so-called Battle of Arie, which features heavily in, in, in just about every film that's been made about our strike and 95, uh, of our comrades were arrested and. Face possible life sentences charged with riot. And the case collapsed when it was found out that, uh, police had forged evidence and had colluded.

And there were identical statements that these pickets, uh, uh, and it turned out that, uh, some mysterious fellow had actually dictated arrest statements to the police who then had to write it out word for word. But some of my, uh, comrades in, I'm now in the Order of Truth and Justice campaign, or we're fighting for a public inquiry to expose what happened. That was June the 18. 1984 when 6,000 police attacked peaceful pickets, 6,000.

Wow. And, and handed out brutal brutality that's never, ever been witnessed publicly on television screens so we had all that and I'm proud to say we stood firm. A whole year. We sustained that against everything they threw at us. They refused, uh, social security payments for, for strikers. Uh, they, uh, they, uh, tried to literally star us back to work, but a marvelous support system.

Much of it fronted by the fantastic women against pit closures, a woman's movement like we've never seen in this country since the suffragettes sprung up and they didn't just feed feeders and run soup kitchens and things like that. Turned up, took our places on the picket lines, spoke all over the country and the world, in fact, raising support. And our communities were solidly. Behind us because we knew, you know, mining in towns and villages are quite isolated.

They only exist because there's a mine there. Sure. And so we were fighting not just for his jobs, but for those communities. And now with the loss of our industries, many of 'em have been abandoned, suffer with drugs and antisocial behavior, the loss of all facilities. And they're being held together by the same people who fought that strike. Trying to keep that, uh, sense of community that's been lost with the mind together. But as I say, I'm proud we withstood all that.

I'm proud that we're still here. We really appreciate you, John. Thank you for sharing with our audience. It's been a, and thanks for showing such an interest 41 years on who've thought that people are still interested in a battle that happened in the eighties. You mean a lot to me, John? I, uh, I, I come from the United Auto Workers Local 2 49. Been there. Oh, brilliant. Well done. Well 26 years.

Uh, so hearing, hearing your story and knowing that you're still around and you're doing the right thing, Many thanks again, John. We'll talk to you later. Thanks to you, brother. All the best. See you a very, very quiet one. This is from a woman called Kay Sutcliffe, who lives in a village called Elham in Kent, and she wrote this when two pits in the Kent Coalfield closed and just shut the other one. So this is for her and them down there. It's called Dale. It stands so proud wheel.

So still I go like, figure on the hill. It seems so strange. There is no sound. Now there and no man on the ground, what will become of their petty yard when man wants trampled face hard tired, we shift on Now having seen the sun, will it become my sacred ground? Foreign tour gazing round, asking if man once worked. Here we beneath the pitted gear. Empty trucks once fell with crawl lined on the will they. All left for scrapped yours life.

The man, the Lord, always be happy for those with the money, jobs and power, they'll never alive. The hurt the he cost, and then he treat like, uh. They always be a happy healer for those with the money, jobs, and power. They'll never realize the hurt they cause and the hatred like. That's all we have for this week's episode of Labor History Today. You can subscribe to the show on your favorite podcast app, and if you enjoyed the show, please rate, review, and share with your friends.

Our thanks to our friends at the Heartland Labor Forum for this week's recording. You can catch the Heartland Labor Form Live at 6:00 PM Central Time every Thursday in Kansas City. Or listen to a recording anytime [email protected]. Labor History today is produced by the Labor Heritage Foundation and the of Its Initiative for Labor and the working Port Georgetown University. And we're a proud member of the Labor Radio Podcast Network.

Please consider subscribing to the Labor Heritage Foundation's Weekly newsletter. At Labor heritage.org. This week's show was produced by Chris Garlock and edited and hosted by myself, Patrick Dixon. Thanks again for listening, and we hope you'll join us again next week.