while slavery and the transatlantic slave trade have been abolished and. These are very much in the past. You know, when you've got a system that's been operating and is well oiled and has created narratives and images and books and songs and all of these things, talking about people in these ways, you don't just overcome that overnight.

This week's edition of labor history today takes us to Australia, but that country's history of slavery and the ongoing failure to come to terms with the resulting racism and discrimination there echo uncomfortably loudly here in the United States as Donald Trump ramps up his campaign to stamp out any effort to acknowledge that such things exist. As though by simply abolishing the words diversity, equity, and inclusion, we can magically erase generations of oppression. It cannot do so.

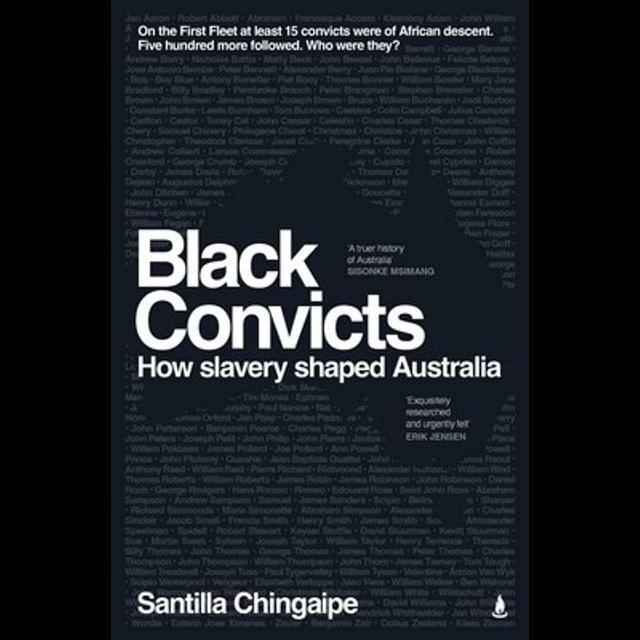

But we clearly have a long way to go here at home and it's instructive and a bit inspiring to hear how our brothers and sisters down under are struggling with the same issues. Today's show comes to us from the Melbourne based Radio show Stick Together. Let's listen in as host James Brennan talks with author Illa Chine about her book, black Convicts How Slavery Shaped Australia. I'm Chris Garlock, and this is Labor History Today.

You are listening to a three CR podcast created in the studios of Independent Community Radio Station three CR in Melbourne, Australia. For more information, go to all the WS dot three cr.org au. Welcome to Stick Together, the National Radio Show that focuses on workers rights, union news, and social justice issues. This show was produced on the lands of the Cool Nation and we pay our respect to their elders past and present.

And recognize the ongoing impacts of colonization Stick Together is produced with the support of the Community Broadcasting Foundation in the three CR Studios Melbourne. On today's show, lucky enough to be joined in the studio by filmmaker, historian, and author of a great book called Black Convicts, how Slavery Shaped Australia San. Thanks so much for coming in the show. Thanks so much for having me, James. Well, I wanted to start with, something that's towards the start of the book.

Mm. And it's about how you, found the seeds of discovering this book. You said that you were an exhibition. Mm-hmm. I guess I'm really interested that just kind of one small part of this exhibition, um, kind of sparked a seed for you to go into a pretty complex, um, and really deep history. Can you tell us a little bit about that? Yeah. Um, as you said, I'd, I'd gone to an exhibition.

The exhibition at the time was, um, at the National Gallery of Victoria and there were two shows that were running parallel. One was called Colony, um, frontier Wars, and the other, I Can't. I quite remember the exact title and they were offering, uh, perspectives on the colonization of, of, of this continent. Uh, there was a European perspective and there was a indigenous perspective.

I. And I began with a, a European perspective because that was just how, um, the exhibition was, uh, geographically placed within, within the gallery. Um, and when I walked in to this exhibition, there was a big label at the front, like most exhibitions tend to have kind of giving you context for what you're about to engage with. And this was, you know, telling the story of British colonization, kind of the story that we get told at school.

Ships arrive, um, land, um, botany Bay and Bus begins the colonization of this continent. You know, convicts on board, of course, but at the bottom of this label, there was a line that kind of spoke to me and it was, um, the fact that, you know, obviously majority of them were British and Irish convicts, but there were also a handful of. African convicts. I was like, what? African convicts? That's news to me. I, I did not know this.

Um, and so I started like, you know, I, I, I'd gone in to see this exhibition. Then all of a sudden it just got, you know, got overtaken by wanting to find out about who these people were and hoping that there was some mention of them within the exhibition. And to my dismay, there was nothing. And, um, and I went home and I sort of thought, let me, let me see if I can find out who they were.

And, um, that essentially became, started the journey of me trying to identify who those individuals were and then verify them. Um, and that led to me uncovering, you know, hundreds and hundreds of convicts as well as settlers as well, of African descent.

with this kind of deep research that you've done into the history of Australia since invasion, I wonder like how has it changed your relationship to Australia and you know, maybe changed any kind of relationship or understanding with aboriginal people and aboriginal culture? Mm. It has added layers that I always sort of intuitively felt were there, as in that the history of this continent is obviously very complex and complicated, but also it's very, very long.

Um, I think I begin the book by telling a story that links and connects, um, indigenous trade with the African continent and, and Asia and, you know, these theories that, um, some, uh, anthropologists and historians, um, are sort of. Investigating that, that seemed to indicate that there wa, there was engagement between this continent and, and others prior to British colonization, which is, for me, was an important starting point because it was sort of like this I, this acknowledgement.

That British colonization is only a brief period in the long history of this continent. It's about 200 plus years. We still don't know enough about the long history of this continent, and we spent a lot of time obsessed with rightly so, but obsessed with this very brief period in the long history of this continent. Although the book doesn't focus on that, I did wanna start there because I did wanna make that point that.

Focusing on a small part of history, but there is a much longer and deeper history, um, that still needs to be told on this continent. But also the thing that that illuminated for me was that Australian history is far more interesting than we were taught. Like, oh my gosh. And there's still things that we still need to uncover and learn about and recover.

And I just sort of thought, gosh, why have, why has our history remained stuck in this certain time period revolving around certain individuals whose story just gets rehashed over and over again? And even then, it's not even a full story. It's this aspects of a story that. Tend to celebrate, um, you know, figures who we deem heroic. When history always tells us there is no such thing as, uh, uh, uh, an unflawed individual. I mean, humans are very complicated.

But in order to understand and, and a figure in history, you also have to look at the context in which they're existing and what has. Shaped and informed the choices that they're making. So even the tellings of some of these figures, um, were shortchanged in that way. And so for me, being able to zoom out and look at Empire, because Empire has largely influenced our lives, um, and looking at the events that led to the colonization of his content in the bigger history.

Of what was happening with the transatlantic slave trade with slavery, um, was a very liberating way of seeing my place in the world. You know, when you spend your life growing up feeling like you don't belong because you're being told, well, you know, um. This is not a place for you.

And to find figures in history who look like you come from similar backgrounds like you, who don't just end up on this content, but who are also part of, um, bigger global histories and have shaped this world, um, was, was very, very liberating for me. I, I will say that and, and it's shifted my own understanding and, of this continent. It's, added more complexity to my. Identity as a black settler in colonized land.

Like, I think engaging with and understanding the nuances and complexities of the dynamics between whether it was black convicts and first peoples, the examples that show up within the colonial archive was also greatly illuminating for me. and yeah, I mean, you know, and even that process brought up, um, feelings of discomfort of, In many ways, disappointment, anger, in some of the individual's actions. and those feelings are all part of the inheritance.

You know, it's, I just think avoiding it or pretending it didn't exist or it, it does, it does people a disservice. And so for me, it colored in things that I. I had long suspected, but has helped me really make sense of what it means to be a citizen in this nation state we call Australia, and I guess it kind of speaks to who generally writes the history and having someone like yourself kind of. Shine a light on.

And you know, I think you do mention in the book having to go through the, you know, the archives of, old newspapers and you know, all the ways in which, you know, this kind of information is kept. Mm-hmm. And having to have like a very critical lens of the way that, those things are written, dealing with archives, colonial archives that are very violent in their nature because of how they record and document individuals like the black convicts. Also took its toll.

I mean, it was not, easy having to sift through document after document that. Describe these people in inhumane and very racist ways, but then also the added layer of also visiting some of the sites. So whether it was going to Barbados and having to hold documents that, um, were from a, the period of slavery that talk about people that looked like you in as if there were property. And this is a very real document, you know, um, that also brought up.

Emotions and feelings that made it very difficult to be very dispassionate as a historian. Um, going to the gallows in Tasmania, um, and standing where many of the black convicts took their last breath was very confronting. Arriving at grave sites, um, their very few places on this continent that I can go, where these individuals are memorialized, uh, 'cause many of them, um, were buried in unmarked graves.

And on the few occasions that I found individuals that, um, have gravestones, it was very emotional. This extraordinary thing happened when I visited a Barbadian convict. I write about in the book James, Robert James. And, um, you know, I'm standing in front of his gravestone and, you know, I, I, I wanted, I just wanted to see it and I wanted to see kind of, you know, like, 'cause I was piecing together his story. Oh my gosh. Finally get to see where his final resting place is.

And then this extraordinary thing happens. Tears just start to fall down my face and I'm thinking, this is not my direct ancestor. I have no relationship in that way with Robert James. And then it dawned on me, oh my gosh, I'm here Because others couldn't be, and on behalf of people that couldn't be because he was.

Just because of the way the empire worked, um, forcibly removed and brought to this continent, uh, never to return to see his family, um, and those that loved him, and I don't think they ever knew that he died or how he died in the circumstances, which all that happened and. It didn't get to properly mourn him. And so then you begin to realize that the work starts to take on an even deeper meaning, right? So it's not just about telling and writing and recording history, it's also about mourning.

Mm-hmm. And you find yourself moving through archives like you're tending to Graves. Um, and so that was a very, uh. Interesting revelation that emerged through the process of writing the book that, um, took, took a toll on the physical body and also just mentally, because it's just. It, it is, well, it's human beings. I mean, at the end of the day, the, the book makes, um, big intellectual arguments. Um, but at the core of it, it's about these human beings who've been forgotten for so long.

And like all human beings, you know, people just want the best for them, for themselves and for their families. Um, and for reasons that I explained in the book, so many of them were denied, even just the basic, um, fundamental human rights. And so that. Yeah, so all that stuff kind of just adds to the complexity of having to document this, these sorts of histories, but also documenting histories of individuals who appear in its fragments within the archive.

'cause they don't appear fully formed because they're not, you don't ever hear from them. Well. There are very few examples where you get to hear from people in their own voices. Mm-hmm. And a lot of the times you, they're recorded by people in positions of power who are not sympathetic to their actions. Um, and so even that power dynamic tells you, it doesn't tell you the full picture of the story. It tells you an aspect of it, but it's not the full picture.

And so then having to try and make sense of who are they? When they're not being recorded in this way. Mm-hmm. Um, that also brought up challenges and made it quite, quite a difficult undertaking in many ways. But, um, but it changed my life. I'll, I'll be very honest, James, like, it absolutely changed my life. I think I naively went in thinking that I was just gonna find these people and tell their stories and, you know.

Uh, but when you're going through documents and finding details, sometimes very intimate details about people's lives that they probably didn't even think people would ever know or find out about it changes you, changes the way you move, it changes how you engage with other human beings. It changes. Yeah. It just, it just changes you and I, but, uh, but yeah, it was, it was a lot. It was like six or seven years of my life, but yeah.

throughout the book you kind of, um, at times touch on some of the things that are relevant to today as well when I wanted to bring some of those things into our conversation today. And so I think, you know, the revelation about the 15 convicts of African descent coming, um, you know, as part of the first fleets and then, you know, the hundreds that kind of followed after that shows like such a long and deep history of African Australians. And you mentioned, you know, the.

Kind of infamous Peter Dutton, uh, comments that he made, um, quite a few years ago now about African gangs in Melbourne. And I just wonder, you know, is this, can we trace this kind of racism that, you know, Peter Dutton and, you know, unfortunately he's gonna be standing in the upcoming election as well, so it's still such a. You know, unfortunately his comments are still prevalent and still, um, uh, you know, relevant.

Can we trace that kind of racism, you know, all the way back to the stories in, in your book? Yeah, and that's what I tried to do. I mean, I begin with slavery in the slave trade because I wanted to zoom out to kind of. See how, how does Australia end up being colonized? What is empire doing that leads to it, um, expanding, um, its territory and colonizing, um, uh, various territories.

And it kept pointing back to sugar because Britain became incredibly wealthy because of sugar, and those profits enabled Britain to expand its empire. So there's that economic, um, reason that leads to, uh, this, this continent being colonized. But then even in thinking about sugar, you're sort of, it was sort of like, okay, what, what was the, what led to sugar being this massive cash crop for Britain?

And you begin to, and then that then led me to sort of looking at the origins of slavery and the, and the transatlantic slave trade. But then also what emerged because how do you start trafficking, kidnapping, holding Africans in inhumane conditions, subjecting them to some of the worst conditions? Um, one of the worst crimes against humanity, uh, in modern history. Exploiting their labor for profit.

You know, so cheap labor, you don't have to, you're not paying people, you're not paying these laborers. Um, but you are, you are using them to fuel the engine of empire. You are using them to be able to grow this cash crop that is heavily in demand, that is reaping massive profits. Um. And that needs laborers. Laborers working in very, very harsh conditions to be able to generate sugar at that scale, right?

And in order to hold these people in that condition, in order to keep people working, um, in these inhumane conditions, you have to arrive at a point where you go, well, we can't quite see them as human beings. We have to see them as something else, right? Mm-hmm. And so this is when. Racism. Modern racism starts to emerge and racism has always existed historically. Right?

But this idea of, you know, discriminating people based on skin color starts to become a, a theme around the period of, in which, um, Africans are being enslaved. And what then. Lays the foundation for what we've now inherited as modern racism is the institutionalization of racism Prior to that point, racism is not legislated. Mm-hmm. You know, but they're these slave laws that I write about in the book that emerged outta Barbados.

'cause Barbados was Britain's first, not just convict, um, um, settlement, but also, uh, it's for slave colony. So it becomes a very useful case study in understanding what then happens here hundreds, uh, a few hundred years later. And so these so-called slave laws, which emerged towards the end of the 17th century for the first time, introduce language that makes distinction between black and white. And it is that that distinction that then starts to shape how.

People are being treated and the narratives are being, um, constructed to essentially maintain this hierarchical order because it's essentially trying to ensure that Africans know their place in this system. Mm-hmm. Um, and while slavery and the transatlantic slave trade have been abolished and. These are very much in the past.

You know, when you've got a system that's been operating and is well oiled and has created narratives and images and books and songs and all of these things, talking about people in these ways, you don't just overcome that overnight. Right. And this is what we're now grappling with. We're now grappling with the inheritance of that. The fact that we have never fully reckoned, we, um, the impact of, um, racist policies of racist legislation, um, and even in Australia.

I mean, you even have to look at something like the, uh, what Australia policy, which, I mean this year is what the 125th anniversary of the White Australia policy being legislated. Again, you know, you've got, um, this system that made it. Legally. Okay. To discriminate people. Who were not British, um, for a good 70 plus years. Mm-hmm.

And then you think about the impact that, that then has had on families, on individuals, but also just because something's abolished doesn't mean that you've fully reckoned with its cultural impact and 'cause a lot of this stuff happens culturally. I mean, it's a language, it's how we treat people. Um, and so for me it was, it was very important to zoom out and say, how do we understand how racism ends up? On this continent, how do we understand how first peoples are treated?

Because once you understand what empires doing everywhere else, because whether it's in Barbados, whether it's in Virginia, whether it's in other colonies in the West Indies, what the British do is that they arrive, they claim that there's no one there. Which they end up doing here as well many years later. And if they do find indigenous people there, they displace dispossess and carry out acts of genocide, um, and then import labor, right?

And we, and we see that model being repeated within every. Territory that they colonize and ultimately, um, it comes as no surprise. It's similar things happen here. And so it was very important to understand that, you know, Australia doesn't just emerge outta nowhere, which is how I think we seem, we seem to see our history that we just popped up an island in Asia and you know, we're not racist, we are not, you know, well, it's like, well, no, we're shaped by empire. Mm-hmm.

All of these things feed and shape how we move, and even the people who arrive as governors, you know, in many of these colonies, have served time in slave colonies. And other territories. So you've got someone like Governor Burke who becomes governor of New South Wales and he's already spent time in Barbados as governor. He spent time in the Cape Colony. You know, where racism and the treatment of indigenous people and black people is very hierarchical. You know, and is legislative law.

And so when someone like that who is then enacting policies here, he's drawing on a lot of that experience that's been shaped by empire. Um, my former supervisor at the University of Melbourne, Zoe Laidlaw, is doing fantastic work in this area, and she's found that something like two thirds of pre federation governors in Australia had served time in Britain, slave colonies. So you can just get a sense of just in that figure two thirds. Mm-hmm.

Shaping policy on this continent, what do we expect is gonna happen, right? 'cause that thinking is embedded into the very fabric of this continent. And so for me, it was very important that we start to sit with this history and start to sit with how it has shaped us, um, as, as a nation.

This kind of story that's often told in Australia about, you know, each kind of wave of people coming, each cultural kind of group has to go through, you know, wave of racism and then, and then they'll be accepted. I mean, we know that that's obviously not true. Um, you know, racism is still prevalent for, for all non-white communities in the country.

As well, but I just, yeah, just think that it feels like the, um, you know, there's still a kind of vitriol towards African Australians a lot of the time and, you know, perhaps unless they're good at sport or something, but there's not the same kind of embracing of, um, you know, African Australian stories of culture of food or those kind of things that have been accepted by some other communities of White Australia. And yeah, I I just, I wonder if that there is kind of a deep.

Just of not understanding, not accepting, not telling these stories. That means that we can't tell the modern stories. It is still told of this, these are new people to Australia or something, but it's clearly not the case. I mean, you know, we, we. Know that probably anecdotally and through other parts of history and, and things. Anyway, there's a lot of, um, you know, stories through music and things like that as well.

But to trace it all the way back here, I, I mean that is such a great observation. Um, and thank you for. Asking, I, you are onto something and, and what you are alluding to is blackness, which is part of another complicated inheritance that comes out of, out of racism and the fear of blackness, right? Mm-hmm. So most summers here in Victoria, particularly here in Melbourne. You know, whether it's the so-called African gangs Apex gang, it's narrative after narrative after narrative.

But then you also get these stories in the media where, you know, you know, it's summer extended school holidays and kids venture into the city. Right. Um, but for some reason when it's a group of black African kids, maybe four of them hanging out, people freak out. Mm-hmm. Somehow that is. A threat. Why is that a threat? Right. You wouldn't say the same thing about four white teenagers hanging out. 'cause they're kids. I mean, you know. Some holidays, you get bored, you venture you, you know?

Um, but somehow that is seen as a threat and somehow that is seen as, oh my gosh, I dunno what to do. And so what do people do? They lean on racist stereotypes to make sense of what really is nonsensical. I mean, why should you be afraid of teenagers? They're teenagers doing their own thing. And so the question should be, why am I feeling uncomfortable? What is it about these teenagers that's making me feel uncomfortable? 'cause they're kids, they're not, you know.

And that's the stuff that seems to, and because again, we don't, we don't talk about it enough. We don't want to sit with this complexity. We don't want to grapple with the fact that we have our own biases, which have been shaped by historical and racist narratives. We try and absolve ourselves and sort of go, no, no, no. Find blame in the individuals. Right. It's gonna take a lot of work, I think.

I think it's gonna take a lot of work to be able to fully see African Australians in their fullness. Outside of the stereotypes, outside of the tropes, outside of the athleticism, as you pointed to, which seems to be celebrated by other, other aspects aren't. Um, I write about in the book about even my own, um, experiences as someone who is an authority and has knowledge on this area, and how even I get written out of my own story. Mm-hmm. Because I am not seen as trustworthy as.

The right kind of expert or authority on Australian history. I can't make people see things that they don't want to see just because they haven't arrived at that point. But what you are pointing to is something very, very real and something that is a very accurate observation. Um, we welcome how we accept and how we embrace African Australians. Mm. And we are very far from being anywhere close to, um, close to that. And you see, I mean, you know, you all just have to do a Google search and.

You know, I'm not wrong about this, but if you do a Google search and just look at the incidents, racist incidents that hap have happened in schools, um, towards African Australian kids, you'll probably find a handful just in the last year alone. And this is go, and this is, and this is kids. And that's where I get really part of the big motivation throughout the book was kids.

I just sort of thought it can't, there can't be other generations that are having to deal with this stuff that are having to be treated. Like second class citizens in their own country. The only way that you can try and make sense of this is by showing people, this is your history and this is where you sit in the context of this history. And this is where everyone sits in this. And if you understand this and if you understand what's shaping these views, what's shaping these biases, you'll then.

Hopefully start to shift how you look at the world. And so how, and it will start to shift how you look at other groups of people, right? Because sometimes our own, sometimes we are limited by our own experiences, right? Some people can live their lives not interacting, engaging with someone that looks like me, right? And so their experiences might be shaped by narratives in the media. And then when they encounter someone like me, that's the first thing that's coming into their mind.

They're going, well, I don't really have. A measure, right? Mm-hmm. Like I don't really have anything that I can kind of like pull on from my lived experience. So I'm just gonna draw on what I've been taught, told through the media, through whatever. Um, but what you also want to remind people is that whenever you are across any person. It's a human being first, right? Mm-hmm. It's not any of the things that we seem to believe or are made to believe, um, about people.

'cause those things don't bear any truth. When you're dealing with an individual, you're dealing with an individual in their complexity. Mm-hmm. Um, and so it's about bringing people back to the basics of what it is to be human in the world, right? Um, and that's hard because, you know, like I said, slavery and slave trade went for over 400 years.

This is a very well-oiled machine of narrative that did a very, very good job of convincing people that there was a difference between black and white. And we are nowhere near undoing. That kind of damage. Mm-hmm. Um, and so all I can hope for is that, um, you know, more conversations, you know, people engaging with history in its fullness, um, but also people just being more open to, um, diverse narratives and stories. And that's where all those things become incredibly important, right?

Because when you're being offered up different perspectives, it opens up. Um, the aperture and you get to see things that you may not have seen or engage with things in different way. And then you're reminded at the end of the day that, yeah, it's just another human being. Well, I want, I feel like I just went to church, the exchange. Sorry. No, I was like, oh my gosh. What? Where did that come from? Sorry. No, no, it was great.

Um, I wanted to touch on, I'm not sure how to segue that, but I wanted to touch on, uh, captain Cook and the kind of revelation in the book about, um, you know, him starting the journey as at least with slaves of his own. And I was thinking about, you know, what. I'm not sure how, that's certainly not something we're taught in school here about, um, that aspect of, of, of Cook. But what did that have, um, you know, him being a slave owner. Mm. What relationship?

I wonder did that bring to him coming? I. To Australia, seeing aboriginal people and you know, that look similar to the slaves that he, he had and that that is a person that he is. I wonder what kind of relationship that had and, and then played an impact on his relationship with Aboriginal people when he invaded the country.

Can I just say thank you because you are the first person that's asked me about that endeavor story, which I think, 'cause when IF when I. I was looking into it, I went, how has this been overlooked? Mm-hmm. Because it is the most documented ship, voyage in modern history. Like their books and books and books and books. I think every, every year there's at least a book. Yeah. Yeah. Published on that journey and even on Cook and, and yet this aspect keeps getting overlooked.

And these people are there. They're, they're recorded and mm-hmm. And so. That. Yeah. So, so your point about what him being a slave owner, I mean, a lot of, you have to, again, think about where Empire is at this point. A lot of wealthy, uh, people were slave owners. Um, this was just the way Empire worked or they had servants Hmm. Um, and Cook. Was operating in the way someone in his position would have operated in that context.

But like I said, you also have to think about where Empire is at this point in history. Um, slavery is very much a part of Empire. Um, cook would've been on, uh. Various VO would've been exposed to, um, what was going on across empire, particularly with slavery in the slave trade. Um, what is difficult to say? Just 'cause I don't have any evidence to suggest anything. Um, and perhaps it needs more scholarly attention.

What is difficult to say is how his experiences being exposed to what Empire was doing then shaped. Um, his views on, uh, indigenous people here? Um, I can't speak just 'cause I don't, I don't, I don't have the evidence. I don't, I don't know. Perhaps other people have looked at it and, and, and written about it, but I can't, I can't speak to that point. But what I, what I can say is that he would, he was absolutely aware of what was going on around Empire. I mean, he had.

Enslaved workers onboard the ship with him. Um, and at another point in the book, I think I touch on his own awareness of, um, the fact that enslaved women were being, um, uh, uh, subjected to sexual violence on board, um, naval vessels, um, so in the West Indies. And so. You know, he wasn't in a bubble or a cocoon in, in that sense. Um, and he was a, a, a, a powerful figure within the system of empire.

So, y you know, and, and absolutely what was going on would've shaped and informed and influenced, um, what he ends up doing here. To what extent, I can't say. Yeah, I think it's definitely just something to, to think about and, and to ponder. 'cause it feels like his image gets softened, um, by some of those books that come out, uh, every year.

In terms of what he, well, it feels like they do portray him at times as someone who just came out on this little cruise and, and discovered something and then just went with the flow of what was happening. But I think, you know, as you spoke about earlier, that this was a, um. You know, systematic way in which these people were, um, you know, sent to different areas to, to learn how to interact with, um, people's land that they were taking.

There was no kind of accidental or innocuous kind of aspects to any of that. Absolutely. And the thing that I, and I, and I think the reason why these stories. Um, to borrow a language of, you know, of softening and how, you know, these figures get mythologized. Um, I write about this in the book about who gets to write history, right? And part of what we have inherited in our historical narratives in this country has been dictated by largely white men.

Um, and a lot of the, the, the dominant narratives have centered around. Heroism around success, around historical narratives that make us feel a sense of pride in our national story. Right and figures like Cook then emerge as singular figures who have done these extraordinary things, very much absolved from the context of the fact that no human being ever does anything on their own, no matter how great that thing is. Right? We are the some parts of, of so many things.

So even that is sort of like taken out of that and just like distilled into this thing that is part of the story, but it's not the full story. And we uphold these stories again as things to celebrate and to venerate and to tell us about who we are. Right? But that's not what history's there for. History's not there to make us feel good or to absolve us or to make us feel a sense of pride. History is there to. Show us who we are as human beings, because as human beings we do some bad things.

Sometimes we do some good things, and sometimes we do things in between. Mm-hmm. And it's not history's job to make people feel a sense of pride. And if that's what you're gonna history for, then you're reading propaganda like it's not, you know, I, I mean, you asked me before about, um, um, how writing this book. Impacted and informed my own understanding of my identity on this continent, particularly with engaging with how some of the black convicts interacted with indigenous people.

Some of the stories I wrote about in that chapter were very confronting for me to write about. Mm. And very difficult. But I also couldn't shy away from it 'cause these things happened. Right. And I also had to sit with the discomfort of the fact that someone that looks like me, um, did some terrible, terrible things. And I think that.

It's a very dangerous thing when historical narratives start to serve a version of national mythmaking where the only stories that are retold over and over and over again are the stories that again, we, we like to make us feel a certain way and the stories that bring up other things, whether it's. Accounts by indigenous scholars that try to speak to the heart of the impact and the legacy of colonization. Those stories don't make us feel a sense of pride. So what? What do we do then?

We suppress those stories. Mm-hmm. Or we overlook them. Or we ignore them, or we, we try and say, oh, well that didn't happen. It, it wasn't that bad. Why can't we just talk about cook? Mm-hmm. And it's like, well, you can't just cherry pick history. That's not how it works. I mean, think about all of the mythologies that we, we tell ourselves, whether it's Anzac, whether it's, I mean, again, they're all centered around a version of pride.

But if you drill into those histories, you then start to look at the complexity of how different groups of people are being treated as a result of the actions of individuals at the center. And I think that's why we have to be very careful. Um, in terms of what histories we're engaging with, what histories were allowed, we, we, we, we are kind of accepting, um, and to also as audiences to be aware that of what we are seeking from history.

Um, like I said, if you're seeking to feel good, then history's not the place. Watch a movie. Like really, you know what I mean? Watch a Disney film. I mean, that will make you feel good at the end of, you know, like, like, but history, you're dealing with human beings. Human beings do terrible things. Mm-hmm. Um, that is just by nature who we are. I mean, look at what's happening in the world right now. You know? Um, there's so much terrible, terrible things that are happening.

We're living through a climate catastrophe. Very terrible, and to pretend that these things aren't happening and to pretend that this is not a consequence of human action is to lie. Um, and yeah, it's not fun. It's not com it doesn't make us feel comfortable. It doesn't make us feel warm and fuzzy. It doesn't hold up individual figures to venerate.

But that's also part of the flaw in kind of idealizing individual because that's a whole, I don't wanna get into capitalism and all those politics, but you know what I mean? Like that's kind of what that leads to. And I just sort of think we have to be very, very careful. I think it's not about good versus bad villains, goodies and baddies. That's not, that's not history. You've been listening to Stick Together with your host James.

Stick Together is a national community radio program with thanks to the Community Broadcasting Foundation and three CR Stick Together is a national radio program that focuses on union issues, workers' rights, and social justice. If you wanna listen back to any episodes of the show, go to three CR website or download the podcast from all podcast apps. Thanks for listening to the show. Remember, wherever you are, whatever you do. As a union for you.

Until next time, stick together and as we finish off the show for this week, we're gonna hear a song from Oow Dreamhouse with Africa Baba from their album from last year. If I be a man, just be a man and be the man that I. If I want to be a man, just be a man and I be a man with you. This world is hard. This world is cool. I want to be, be able to, I. Stay tuned. Be by your side all the time. If I had to be the stronger one, it won't be fun.

And I know I don't lie because this walk can be so raw and this walk can be so cool and I'm trying to me. You've been listening to a three CR podcast produced in the studios of Independent Community Radio Station three CR in Melbourne, Australia. For more information, go to all the Ws dot three cr.org au. I'm Rick Smith, and this is Labor History In Two. You may know that March is Women's History Month, but did you know why it takes place each year in the month of March?

It all goes back to today in labor history. The year was 1857. That was the day that hundreds of women working in New York City's garment industry went on Stripe. The women demanded better wages, safer working conditions, a 10 hour workday and equal rights in the years that followed the historic strike. March 8th became an important time for women workers to rally in the city. So on March 8th, 1908, a crowd of 15,000 women workers in New York took to the street.

The marching women demanded the right to vote, an end to sweatshops and a halt to child labor at the International Socialist Congress. In 1910, a German woman named Clara Kin proposed March 8th, be declared as International Women's Day women from 17 countries agreed. And over the years, the day continued to hold a special place for women in the labor movement. Women from Bangladesh to South Africa to Venezuela have held demonstrations for workers and civil rights.

On this day, by 1980, president Jimmy Carter declared the week's surrounding March 8th Women's History Week. His declaration read in part too often the women were unsung and sometimes their contributions went unnoticed. But the achievements, leadership, courage, strength, and love of the women who built America was as vital as of the men whose names we know so well.

In 1987, the week was expanded and March became known as Women's History Month, and it all started with garment workers who were not afraid to stand up for their rights. Leading the way for countless numbers of other women who have bravely followed in their footsteps. Labor history in Two, brought to you by the Illinois Labor History Society, and the Rick Smith Show. For more information, go to labor history in two.com. Like us on Facebook and follow us on the Twitters at Labor history, YouTube.

That's it for this week's edition of Labor History Today. You can subscribe to LHT on your favorite podcast app, even better. If you like what you hear, hope you do, please like it in your podcast app. Pass it along and leave a review that really helps folks to find the show. Labor History In Two is a partnership between the Illinois Labor History Society and the Rick Smith Show, a labor themed radio show out of Pennsylvania.

Very special thanks this week to our colleagues at the Always Wonderful Stick Together radio show. Australia's only national radio show focusing on industrial, social, and workplace issues based in Melbourne, Australia, and distributed nationally on the Community Radio Network. Labor History today is produced by the Labor Heritage Foundation and the Cal Benefits Initiative for Labor and the working poor at Georgetown University. You can keep up with all the latest Labor arts news.

Subscribe to the Labor Heritage Foundation's free weekly [email protected] for labor history today. This has been Chris Garlock. Thanks for listening. Keep making history and we'll see you next time.