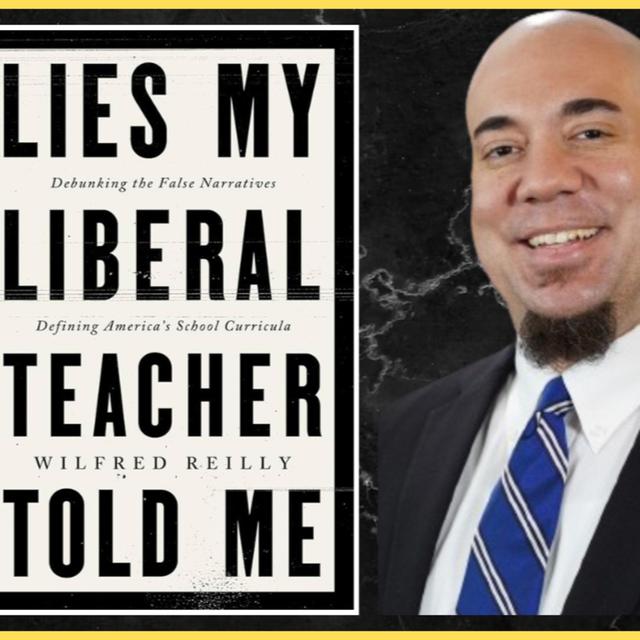

Welcome to Keith and I don't tread on anyone in the Libertarian Institute. Today I'm joined by Doctor Wilfred Riley, author of Lies My Liberal Teacher Told Me. I have read the book. I absolutely loved it. Doctor Riley, where is the best place for people to buy Lies? My liberal Teacher told Me. Probably the best single place to buy the book is Amazon because that makes it possible to look at concentrated sales in one kind of location.

But the book is available, you know, everywhere fine books are sold, the books carried by, you know, Target, Walmart, Barnes and Noble, all the major, the major book houses. But most of the purchasing we've seen goes through Amazon and that's the easiest way to track purchases. I have one of the author central pages on there and so forth. Sounds good. On page 125 you mention the importance of falsification when looking at historical

narratives. What does it mean to falsify a historical narrative or general theory? So you said page 125. Yes. So this is in reference to colonialism, but specifically it was the one place in the book you mentioned the importance of falsifying theories. So before getting into the specific material, what does it mean to falsify a theory? Yeah, the the idea of falsification in science really gets into the philosophy of science.

So this is there's a very famous philosopher of science known as Karl Popper, who really developed a lot of what would be thought of as modernistic scientific theory. So not postmodern, not pre modern, but what when I went to grad school, almost everybody kind of trained in. And one of Karl Popper's ideas was simply that there's a whole formalized scientific method, of course, which is now well beyond the the four steps he used in high school.

But one of Popper's ideas is simply that the theory is not really scientific unless you can falsify it, unless you can prove it wrong. So when you talk to someone who's a postmodernist 4th wave feminist writer or something like that, they'll often say, well, I know what I know, which is that the the world is ruled entirely by wicked men or something like that, based on my lived experiences.

And so the this paper that I've written is a series of seven anecdotes about my life growing up as a black girl in New Orleans. And no, I won't be taking questions. And the traditional perspective in science is that that is almost worthless, that you have to be able to look at the claims that a theory would logically make and look at the things that would be predictable and discoverable if the theory was true.

And look at the things that would be predictable and discoverable if the theory was false and determine whether or not the theory is true or false. So a claim is only scientific if it's prone to be falsifiable. For example, if I argue that the this is actually something that I would be interested in testing, but that if you are an actual genetic hereditary. This is one of the groups that debates the topic of IQ.

If you believe that there is human genetic variation in IQ and athleticism, you would logically expect both the lowest and highest I QS to be found in Africa. Just as you would expect the most and least athletic people or biggest and smallest people to be found in Africa. Because the widest range of human genetic variation exists on the African continent. And this is probably true.

Actually, as we get improved schooling in Africa, we see groups like the Nigerian Igbo. No, I think IQ is very heavily mostly cultural, but we see groups like the Nigerian Igbo performing at East Asian levels. We see other countries are still testing in the 70s. I think that'll change. But if it doesn't, that's actually a pretty strong argument for the hereditarian position. But that whether whoever's right, that's a testable

scientific claim. That's sort of a standard claim that you'd see a broad IQ range on the continent of Africa and it would be broader than what you see on the continent of Europe. I guess the point is that many postmodern theories aren't testable at all. And I, I think my point there was that I was agreeing with Doctor Bruce Gilley that a lot of the things that are said about Western colonialism aren't testable.

So Doctor Gilley says that when you look at the impact of Western colonialism on, say, East Africa, which itself is a pretty civilized region, Zanzibar, Kenya, so on, it was good. You can look at how many railroads they had before, you know, the white man came, you know, what were the Arabs doing? And then you can say, well, after the white man left, they had state acts. I believe it was as many rail rights.

So sure there was some war fighting, but the white guys built a lot of rail rates and built a lot of schools. This. You can't just say this was a bad thing. The anti colonial argument tends to be something along the lines of but what price freedom? It moves from the testable, it moves from the scientific into sort of the very airy, you know, the the argument that there's nothing, there's no price that can ever justify a black man being ruled over by a white man or something like that.

And what the good doc is saying and what I think I would agree with is, well, that's a worthless argument. You can't that's not a scientific argument. You can't say, well, there's no price that's worth having a black leader instead of a white leader. I didn't say that extremely well, but that's just a meaningless racist nonsense. And I think that very often when smart people engage awoke and sometimes dissident arguments, you kind of get that feeling like, what is this horseshit I'm

looking at? You're not, you're not making a claim. You're just you're sort of just saying things. This is like the essay sort of arguments, like when people start saying it as a Christian, as a black girl, and you just kind of look at the text and you're like, OK, this probably isn't going to be something that I can break down in mathematical terms, right? You mentioned in that section, I know you just touched on this, but you said in every transition there are trade-offs.

Why is that something important? Well, that that again, I mean, so we're we're really just kind of breaking down. I think this might be kind of for the benefit of the audience. We're just breaking down some of these core principles in economics and political science. I mean, this is the great we already did Karl Popper. This is the great Tom Soul who's giving advice to leaders in basic economics. And he says, remember, there were very few solutions.

There are a lot of trade-offs. So a solution when you're thinking from a leadership perspective is a decision that eliminates a problem with very few corresponding new or reciprocal problems. So you just, you know, you eliminate the issue, you get it out of the way. There may be a cost upfront and say cash money, but then it's gone. In reality, what you most often encounter are trade-offs where you eliminate a problem, but in doing so you create one or more slightly smaller problems.

The classic example that's sometimes used is the green revolution in foods. We had a problem in the world with starvation. I mean, a large number of countries like Vietnam was not uncommon for natural starvation diseases like Coachacore to be very prevalent among young kids. So we literally developed, and the Western world deserves a lot of credit for this. We developed, for example, new varieties of rice and wheat that, you know, but not but that, you know, more rapidly or whatever.

And so we were able to feed more people. But the flip side of this is that as more food became available in a, you know, happily capitalist, rapidly processing world, people became more obese. So we're now dealing with these problems of obesity, and in fact, the total number of deaths from misconsumption of food has remained quite similar. So it's very hard to solve a problem. It's very hard to eliminate an

issue like bad diet. What you normally do is you knock down one mole, and anyone who's been in the leadership role knows this, and then another problem comes about as a result of that. So for example, men and women interact in a set of predictable ways. The two groups are sexually attracted to one another. Offices interestingly, they've always been hotbeds of actual sex, something you find out kind of disturbingly, if you're ever in charge of running an office building.

And so you have to you have to kind of deal with that. Now traditionally in the past, businesses have had a kind of ass slapping sort of harassment culture in place, which is is annoying. No one really improved fit. So you've seen movements like me too that are designed to kind of clutch that. The problem turned out to be that many men and a surprising number of women sort of liked that and it became part of internship.

And as people became more and more afraid of dubious harassment charges, you've seen a shunk decline in mentorship, especially mentorship cross sexual lines. So mentorship, which is a key part of the junior executives life for men of women and by the way for women of young men has dropped something crazy 7080%. So it's very hard to just get rid of a problem. You normally get rid of one element of a problem and then immediately face another element

of a problem. So we're in corporate America. I don't even know what they're going to do about the mentorship issue. It seems like they're now trying to bring back things like retreats where they isolate people together and so on. They're just going to return to, you know, what was, what was going on before. So that is, it's the circle of life.

They always have a number of trade-offs in mind when I say, you know, I think it'd be really important and empowering if parents had school choice and they weren't restricted to whatever district they have. Immediately you get a long list from the progressives about all the terrible downsides of if parents or black parents we could use specifically had the

freedom to choose. Well, unfortunately a lot of the parents are ignorant and they wouldn't know what school to sell them to. This might allocate money away from poorer schools and give it to richer schools that already have enough funding. They have a huge list when you want to introduce one new little freedom, they have a ton of

list. But when it's like, well, you're changing who is calling the shots for a number of African countries, they're like, Nope, no tradeoffs, that there's only a benefit and that's increase in freedom. So it's certainly seems like they accept this principle, but only in certain aspects of of life.

When it comes to trade-offs, let's look at very difficult examples of people who supported slavery or at least opposed abolitionism when it came to opposing busing, when it came to opposing civil rights, when it came to opposing gay rights. What were some of the trade-offs and constraints that people at the time were facing when they were looking at issues like this? Well, I think those are those things are all very different from our moral standpoint today.

What I want to say, of course, is that our moral standpoint today is a very unusual 1. So this gets into the whole idea of presentism, which is that you can't judge the opinions for the behaviors of people in the past by the moral standards of today. Most social scientists, including me, think that ultimate morals don't exist at all. I mean, whether God agrees with that, I suppose, is a discussion you'll have with him or her after death if you know such a

being exists. But in terms of the codes in society that, like an honorable warrior, follows, there are about 12 things that are universal over time. And I'm I'm willing to concede those are things like don't rape kids, few exceptions, southern ancient Greece and so on. But in general, like everyone kind of agrees on that one. Don't eat people unless you're starving it. OK, Beyond those 12 baselines or anthropologists, I think you're

adding another one or two. The reality is that the basic opinions on things like sexuality, the consumption of psychedelics and other drugs, consensual dueling among males, rating and trading like almost everything have actually varied widely across society to a point where it's kind of silly to

pretend this isn't true. I mean if you compare highly civilized cultures, the Romans, the Aztecs, the Japanese, the Arabs and US today, the Americans, the the core ideas on almost everything are completely at odds with one another.

I mean, Thomas Jefferson, who's often criticized by contemporary kind of pro woman or pro black scholars as being a rapist and so on, would be absolutely horrified by only fans where, you know, the day you turn 18, you can go online as an actual prostitute and start having anal sex with strangers and make

millions of dollars. So I mean, I'm not entirely sure we're in a moral position using most standard Christian or Muslim or whatever codes of ethics to criticize, you know, most groups of people in the past. So the the non present is standard you would use. I think if we're looking at people in moral terms would be sort of, you know, if we accept these rules at all. How did people do in the context of the morality of their arrows? It's just meaningless in in their society.

It's just meaningless to look at Shaka Zulu and say, well, he was a rapist slave trader. Well, of course, because he was an African cake. I mean, it, it, there's no, there's no context in which Shaka Zulu would be expected to have host Christian quote UN quote slave morality. It's just absolutely absurd. You'd have to find a Zulu or by the way, an almost identical Viking standard and hold him to that. By that standard, he was a bit crazy, but he's a pretty good, pretty good leader.

I mean, I've heard of the entire country for his people.

But anyway, so the point that I'm making here is it might sound absurd to us to look at the idea of trade-offs in some of these situations, but that's because we're imagining the existence of a moral system that even today we imperfectly follow and which no one alive at this time, of course, had ever even heard of. So, I mean, in the case of fraying the slaves, they're obviously a large number of potential trade-offs that were envisioned.

The the most basic was that in in America where it was understood that violence would be required for that you'd have to fight a massive bloody war to set the, the enslaved population free. I mean, that's that we forget this now because we accept that the Civil War took place, but the Civil War was the most violent military conflict in American history. The total number of casualties

was about 620,000. And brother fought brother in the South, one in four fighting men, men of military age and reasonable physical fitness was killed or injured. I mean, there were also a number of battle casualties beyond the 620 thousand were killed. So people had their legs blown off, their arms blown off. So on every building in the South over two stories, at least along Sherman and Grant, some marches was burned to the ground. So that was the primary trade off.

We knew we were going to have to do this. And then the question was, what do you do with the freed slaves? You're you're going to have a population of people from another society. And all of these were warrior societies at the time. These were bought to West Africans mostly, many of whom had only been in slavery for a couple of generations. If one, in some cases another population from another reasonably developed society that didn't much like this society in the country, what are

you going to do with them? Are they going to assimilate or are you going to have a permanently hostile, you know, quote UN quote alien minority in the country? And in fact, whites and blacks have adjusted to one another fairly well by world standards in the USA. But the the primary idea at the time was actually what was called colonization. We were going to take black Americans and send them back to Africa.

And that actually led to the creation of the nation of Liberia, which is one of those great historical stories where, I mean, under a black general, a bunch of black freed slaves came back to Africa and took over a country. I mean, they had conquered the local people. They built a pretty good sized city. They set themselves up as kings. They established a local democracy, at least for the descendants of American slaves, so on down the line. But, you know, the, those are

the obvious trade-offs. What is what's going to be required to free this group of people? And then what's going to happen to them? Is there going to be constant, incessant lower level racial warfare? In terms of the other two cases, the the trade-offs are a lot clearer. I think most people today and even many people in that era would say, well, slavery is bad, it can't have slaves. But in terms of busing, for example, busing, the trade-offs obviously outweighed any of the benefits.

That's why we stopped busing. Busing, for those that don't know, is the practice of taking people from school with one racial composition and moving them to a school with another racial composition to get sort of racial equity between the two schools. And busing was extraordinarily unpopular during the 60s and 70s. And in part this was because wealthy schools almost invariably managed to avoid busing.

So what you'd have is sort of like South Boston High School, which is a legendary Irish and Italian high school, being bused, and combined with Roxbury High School, which is a high school in a black ghetto, and the results were pretty much what you'd expect. They were like the football team was pretty good, but if you went to the school, there was this constant violence and brawling, you know, 50% non attendance, a lot of interracial sex and hooking up apparently on both

sides. But you know, a lot, a lot of people became pregnant and eventually they just discontinued the experiment. But the, the trade off there. On the one hand, I guess the benefit is you're seeing racial integration, which was presumed to be a good in, in and of itself. The negative is that you're seeing violence, you're seeing lowered educational performance. You're seeing, I'm sure you're seeing people become more

racist. I mean, like I had a lot of buddies along ethnic lines, but I went to an integrated quote UN quote hood school in the 90s. We had blacks, Hispanics, Irishmen, Italians, all that. And I mean, it's got a long 5, but I'm not sure it it reduced stereotyping. I'm not sure people left thinking that African Americans or poor whites were less criminal than they had believed when they went in. So busing, I mean, the the trade-offs or the negative backlashes outweighed the

benefits. Gay rights is an interesting one. Not to just yap on for 10 minutes straight, but I think that when most people who were urban kids who enjoy dancing and sex, I mean, like I was a former raver when most people who were in one of the city scenes, hey, punk, hip hop, whatever, talk about gay marriage. It's with a little kind of disillusionment because the assumption in the 90s, the 80s and 90s was just this was one of the yeah, OK, whatever, Rocky Horror, like we'll push it

through. This is the last civil rights movement, God damn it. We'll get our gay buddies their rights, then it's over. Everybody shuts up. We already heard this from the blacks. The Irish got theirs in the 40s, Jews, but that around the same time women where we have all these feminists all over the place. This is the last one.

And I think that gay marriage seems like a really basic thing, like what the gay movement, the gay activist movement HRC Solon was asking for was to become bourgeois. And to some extent that's really deep. I mean, other than Martin Luther King, that's not what any radicals before had really ever asked for. You know, the, the core of the feminist movement was, you know, equal rights and checking accounts, Sure.

But also we wanted to demolish many of the traditional gender roles, which is, by the way, a terrible idea. On the core of the black radicals, the Huey Newtons and so on was, you know, we want to violently take over X percent of the leadership slots or change the structure of society or make society more Marxist. A lot of incoherent demands, but gay people are just saying like, look, we want a cat by the fire. We want to mainstream this type of love, which has been very

common since ancient grace. So I mean, initially there didn't seem to be any trade-offs at all. This is something where you saw support kind of, we call this a ski slope graph. We saw support go up just dramatically through the 70s, eighties, 90s O OS. You might correct some of those decades, but the gay marriage with the state laws beginning in the O OS and then Obergefell became a reality. I think we saw subsequently that the one trade off was acceptance of movements traditionally

considered deviant. Blame the gay community for this at all, actually. But immediately following the O Berserfeld decision, I actually was a canvasser for the Human Rights Campaign for I was a canvas manager. Like I took a lot of our teams out in Chicago for like years now. I did it as a college job. I wasn't like, I don't have a rainbow flag tattooed on my body or anything. It was kind of moving, you know, we saw some wins. I actually quit.

I quit this and got a job on basically the trading floor. It was a sales bullpen. We weren't primarily in security, but very high end, like 6 figure deals. I quit and got that first sort of junior executive job like the year before Albergefell happened. So I was fairly tied into all of this. And when gay marriage passed, I mean, I remember calling some of my old friends and saying again, hey, that's it.

This is this is over. I'll never see another one of those damn HRC fundraising letters again. Because by this point I started making money and they were contacting me like. You know, 2% of $300,000 is only, you know, So I thought this was the end of it. And the next year I remember as their fundraising cycle and they sent me this brightly colored missive that had a new flag on it. It was pink, white and blue. And it was like, Are you ready to support our transgender

rights campaign? I, it was, it was what they call foreshadowing in the writers trade. Like, I didn't quite know what it was yet, but it was like, oh, they didn't stop fundraising. They didn't take a two year break like some of their executives implied they were going to. It's this new thing.

And I don't, I don't really know what this is yet, but I, I think the trade off was that as the gay community got through the door, we found out that many, many more people had identified sexually in ways that were not yet being talked about.

So I mean, like kink was something that like your girl would ask you to do at 1:00 AM. Like there wasn't a BDSM community, there weren't people walking around with, you know, the sex worker red umbrellas or with like balls in their mouth in public or with like sub collars on even in downtown Chicago at this time. And any of the the other things that went along with that being not trans or people with gender dysphoria, I'm sure, but like being non binary didn't exist.

Being ace, Like the idea that if you wait three days to have sex, you have a sexual identity that didn't exist. So all of that kind of came through the door next. And I get the feeling from old lion gay male buddies that the gay community has almost been pushed out of the gay movement where the rainbow flag now is a block of all this crap and then just the actual rainbow flag. So that that I think was the

trade off. It was a subtle and submerged trade off that as you extend equality, you recognize that they're always going to be more minorities. The most impressive, or I shouldn't say impressive, the most surprising statistic you give is you're quoting either Gallup or the New York Times from the 70s where you say 4% of white supported busing, which I figured it'd be something like

that, and 9% of blacks did. That shocked me because the way it's sold is these people were fighting for these busing rights, but the whites in power just wouldn't give it to him. And then the blacks finally won their rights. So to find out that it was 9% was very shocking. I want to keep going in this direction. You have a section on white flight. Here is how white flight is summarized by Ibrahim X Candy.

He says the ghetto had expanded into the 20th century, and it swallowed millions of black people migrating from the South to western and northern cities like Philadelphia. White flight followed, but the word ghetto, as it migrated to Main Street of American vocabulary, did not conjure a series of racist policies that enabled white flight and black abandonment. Instead, ghetto began to describe unrespectable black behavior on the N broad streets

of the country. What is left out of the white flight narrative that Ibram X Kenti tells us about? Well, I think there are two different things there that are worth pointing out. So first of all, when you, you seemed a little surprised that only 9% of blacks supported busing. It's it's worth recalling when I said there were different moral systems in previous societies. It's worth recalling that the moral systems of previous societies worked pretty well. This is a point that I try to

emphasize. So I mean, obviously no one wants to return to these in entirety, but like when you talk about the somewhat segregated, say Upper S, lower North, the the system wasn't one where if you saw a black guy or a white guy walk by you on the street, you had to fight it. What that meant is that there were things like restrictive covenants in place in terms of who you could transfer your business to, anyone black or white, ethnic white.

There was some question about the how Jews, Irishmen, so on ranked in societies. I'm sure you understand, but I mean, like any of these groups could own a business. In fact, it was much easier to do that at this time and so many ways this was a much better society. Members of all of these groups were expected to take care of their children. Very little tolerance for father abandoned and so on down the line.

There is just one problem in society, which is that racism was more sure there are other problems. We're fighting the Russians or whatever in terms of race relations. The sole problem was that racism was more tolerated. I mean, the black business sector, if you think about black Wall Street and so on, was in fact significantly stronger at this time.

So what you had was a pattern of separation of neighborhoods of the kind that you'd find and say upper middle class India Today where you'd have the blacks here and then the Italians and the Irishmen and Anglo whites. They might have gotten the one hill in town Anglo whites. They didn't have like your one block Chinese neighborhood and so on. You're talking about a mid sized Midwestern city here.

And these people didn't hate each other or love each other, just didn't interact with each other very much. And there was some legal discriminations in place against the members of technical minority groups. No one approves of that. But the idea that the black school in town would have been wildly nonfunctional is, again, a presentest assumption. Tom Soul actually looked at the black schools in New York in the 1940s and has a quote about this where he says, well, no, in Harlem.

I mean, sometimes we outperformed them. He's talking about ethnic whites in the Lower East Side. And sometimes they outperformed us. Now, all of us would have been testing it like IQ 89 at this point, but there weren't any major differences within that working class Clay, to the population. And as far as I can tell from checking his data, that's

correct. So I mean, the things that really devastated the black community where when you think of a black community, you think of and again, this, this might have been a little different in the South. I'm sure there were some kind of third world like villages adjacent to plantations and so on. That's not something I've researched.

But if you're talking about a black community in Cedar Rapids, IA, in 1950, I mean, the things that are associated with ghettos today, like widespread fatherlessness, high crime involving guns and knives, that kind of thing, those would not have been any more visible or certainly they wouldn't have been more than twice as visible than they were in surrounding

rape communities. So I mean, the getting to the point where they were very common took a lot of things, some of which had to do with racism, most of which didn't. I mean, you're talking primarily about Lyndon Baines Johnson's Great Society welfare programs. Like everyone on the right says this like we're invoking our catechism. That's because we're career, right? I mean, there was literally a program, pay per child welfare, where you got a certain amount of money, usually in the

hundreds of dollars. If you had another kid. One caveat was that you couldn't have a married male in your house. This absolutely destroyed both black and poor white families. I still see its impacts. Down here in Appalachia. We don't have a lot of black people. So, I mean, you had this, you had the liberalization of the justice system in the 1960s,

blah, blah, blah. But the the basic idea that black people lived in dysfunctional squalor in at least the Upper South or the Midwest or whatever, and would be expected to want to be around whites during a time when the two groups were clashing. Yeah. There's there's really not much basis for that at all. And I think this is true whenever we look back at these historical roles. So, I mean, I think, for example, feminist writers, and I don't mean to bash the feminists

here. I've been arguing with them online for a couple weeks. Obviously it's good that we have women's rights and you could be an executive as a woman and so on. You know, men now know what female orgasms are like. There are a lot of positives

that have come out of feminism. But I mean, the one of the things the feminists did was very intentionally, if you read the Beauvoir later, it's on target housewifery and try to dishonestly present the idea of being a healthy mother to your kids as unappealing because this is such a natural role for so many women in particular, but so many members of couples. So I think a lot of people would sort of default assume that the the existence of, you know, an upper middle class woman in 1955

was sort of horrible. Like you're on pills, you can't have your own money, your husband physically or sexually abuses you. Not really. I mean, there were some problems with the law at this time, like marital rape technically wasn't possible in either direction, although statistically it was not particularly common. I'll also note like the physical abuse wasn't possible against men generally. So like if your wife hits you with a skillet, you couldn't press charges.

But overall, like in the typical family, women ran the budgeting so your husband would come home with a pay envelope and give it to you and you'd make all the purchases for the household. Like actual reports of domestic violence, like some of this may have been due to reluctance to complain or something like that, but were significantly, significantly lower than they

are now. Where you have a lot of people that are not married living together in sort of family style situation shifts with multiple kids from different relationships and so on. So I mean, the basic idea that women running the home and men working outside it was totally unsustainable and men were brutalizing their wives and wives are stabbing their husbands and so on. There's, I mean, the murder rate was sort of what it is today. There's no evidence of that at all.

So anyway, the the basic idea that systems that we now disapprove of because they had real flaws, like it is good we have female executives now, but that those systems were non functional and they endured for 100 years just for some reason that that doesn't ever stand up. It never makes sense. But to get to your point, and I'll because I went on about that for like 5 minutes, I'll say this quickly.

Like Candy is kind of doing this a, a variation of what I'm criticizing when he talks about like the language he used there, like the ghetto just spread. It just expanded. Whites began using the term the ghetto to describe the black people. It's as though he's describing magic. And this is the usual description of white flight. Like as black people came to the north for no reason or for because of pure racism, a second phenomenon happened, which is that white people began to

leave. And I, I think that it's, you know, sounds a little brutal to put it this way, but people like Tom Soul would say, well, no, there's an obvious interrelationship here as black people. And by the way, the 1st wave of third world immigrants came to the North. And as policing liberalized behavior, there's the intervening X variable here caused many people to leave the urban inner cities. Like, so white flight didn't happen in a vacuum, basically.

Like as you had a lot of black migrants from the higher crime South and support white migrants as well. And as you had a large number of immigrants from generally higher crime states, crime increased. And as crime increased, a lot of people fled the cities. So I mean, there was some racism tied in here. I mean, there was a practice called Blockbuster, but even that it wasn't just like racist

guys decided to leave. It was sketchy law firms, generally led by people on what we call the left Democratic contributors hauling up these ethnic neighborhoods and saying like, hey, buddy, you know, they're coming in, you better sell now or you're going to lose everything you have. You know, there was there was a concerted effort by kind of sleazy downtown businessman to move people out of these traditional, you know, Irish, Italian, whatever neighborhoods.

So as you had people moving in, you had crime increasing and you had people really try to push out the people that were living there so they can take these houses on the cheap. You saw people leave. You didn't just see people leave because they was racist. One final statistic on crime. Let me actually pull this up. It's a site I often use to make this point. This is Disaster Center. It's one of the few sites that puts together both the BJS and

UCR crime numbers. OK so crime increased by about 500% and black crime increased by about 800% between the years 1963 and 1993. The center right columnist Mona Sharon has a great book about this called Do Gooders. But OK so in 1963 let's look at murders. You had 8530 murders according to disastercenter.com. Now in 1993 when I was roaming the the streets of Chicago in my giant rave Jinko's, you had 24,530 murders.

So I mean during the period when white flight was occurring, like murder in the cities went from, you know, 8000 with basically the same population. We're talking about a 2530 year window to 25,000. Aggravated assault in 63 is 174,210. Let's see what it is in 93, 1,135,610. So I mean, that's that's a huge part of the white flight story that it would just became untenable, as Jack Cashell puts it, to live in a lot of these

neighborhoods. And you also said, is it reasonable that transportation, access to transportation, actually increased the amount of all people moving? For example, candy just runs over the fact that there was black flight from the South to the north and then white flight. I don't know why he only calls it flight when it's one group, but maybe transportation could explain why there was so much movement. Because people now had opportunities they didn't previously have.

Yeah, that that's correct. One thing I try to do in this book is throw in some of the dull social science where it's not just, we're not just talking about like black crime and Rick resistance to it and so on. But it's also just like there were a lot more streets after the 1945 Roadways Reconstruction Act sort of thing. Yeah. I mean, one of the things we forget is that suburbs didn't

always exist. So I mean, the traditional model, which has been called the post Roman model for countries, is that you have a city and then you have a countryside that feeds the city. The idea of a bunch of people living in big houses with like 1/4 acre of lawn around them that doesn't grow crops is very, very new. So in order for white flight to occur, and as you mentioned, yeah, there's a lot of upper middle class black flight, Asians are more likely to live in the suburbs than any other

group. I don't actually understand hostility toward the suburbs in the 1st place. So I mean, the whole white flight thing comes up in a broader conversation between urban people and rural people and people who just hate the whole idea of the Brady Bunch. Anyway, like the for a white flight to happen, there had to be a bunch of things like people had to regularly have personal vehicles that have cars. You had to have roadways that could take people in cars outside of the cities.

You had to have incomes that could support people buying either a first or second home outside of the city. So I mean, it's a white plate chapter. I talk about all this like I talk about suburbanization beginning. I mean, remember, Lebanon was only built in 1951. And a lot of the things in this book used to be the core stories we told the kids, like us building the railroads across the country, you know, us building Leviton in the suburbs. So mom and I can come here and

give you guys a nice life. You know, dad points at the yard outside. You know, a lot of this the Wright brothers building the first airplane and managed to squeeze into the book. A lot of this has been kind of tossed out in favor of this specifically civil rights and Vietnam narrative from kind of the post hippies, I think, where like almost every story involves black people or natives in some way. And I'm black and a bit native.

I don't, you know, I don't mind that bit native at least per family legend, but like it doesn't really have that much to do with the, the core tales of the country. So I, I do try to give back a bit of that. But anyway, the the whole point is that, yes, like suburbanization, the growth of the automobile, the growth of the roadways, yeah, all that contributed as well. So central one thing I will last line.

If you go to like Wikipedia or Britannica and you look at the population of every city in the country, whether majority white, majority black went out, you'll see what's called the American pattern, where the city will grow massively in size until about 1960 and then it will shrink. And this has nothing to do with racial conflict. And a lot of these cases, I mean Mobile, AL, where you got middle class blacks and whites living together, Boise, ID, I bet,

displays this pattern. What it means is that those cities, more and more people move from the country over time, more and more farm kids moved into the city. It became a whole thing. This is what Guns and Roses and all those bands from my childhood sucked by like just a country girl, you know, going in to be a waitress or to work for an ads agency or whatever. But eventually people started moving out. You go into the city, you move out into the exurbs. That's that's it.

So like actually like mobile AL is a good example of this. Like, this is just a totally typical city of its size. Let's see what the population here is. I looked at this for a consulting gig like a couple days ago. Not going to waste too much time on this, but yeah. OK. So like 1920 sixty thousand 1930 sixty 8019 forty 78,019 fifty 129,000. It's after World War Two that people really started leaving the farm.

And there were songs about this Like you can't keep them down on the land after they've seen Gay Perry 1962 hundred 2000, then 1970 a 190 thousand 1980. It's a pretty stable 19 ninety 196 thousand, 2198 thousand. And now it's down to 183,000 and it looks prone to shrink still more. And that's actually less shrinkage than you see in most places. Sunny room. That's that's all part of a pattern that's pretty universal.

When it comes to the origin narrative that liberals in general refer to, they will start with the very dangerous result of mass immigration from Europe to America, where the natives were living. I found this 5 second clip which summarized how my liberal teacher actually explained things to me. Wow, you're a different color than me. Would you like to be equals? So for those who are just listening to the audio, it was a black gentleman and Family Guy saying would you like to be

equals? And the white person just throws them in a net and kidnaps them. That is generally how I thought things went down. What is either omitted or outright deceptive about the liberal telling of Native American, US, European relations? Well, I mean that that whole story in the context of either root style intervention in Africa or Native American is a

complete lie. I mean, so first of all, it begins with the ultimate lie, which is sort of that savages, if you will, like people living in the the state of nature or close to it, were peaceful and calm. That's complete nonsense. First of all, most Native Americans weren't savages. The Aztecs built giant cities. And secondly, secondarily, people that were aren't kinder than anyone else. So one of the great left wing fictions is that this computer actually is running low on

battery. It might die soon, but it's the worst. We'll switch to another computer or something. One of the one of the great left wing fictions is that human nature is itself sweet and kindly and it's corrupted by something else like capitalism, toxic masculinity that's taught to sweetly innocent boys by their abusive fathers or something like that. And this is actually complete nonsense.

Like if you look at other animals like both male and female chimps, this, the 100 studies have been done here, they're actually a lot more aggressive and vicious than we are. Like, if anything, what civilization does is restrain that savage instinct that humans have that made us feel kinship with and domesticate wolves.

You know, So the, the idea on a certain part of the political left, which is unfortunately really over represented in the field of anthropology, is that if you come across people in their natural state, just like hunting in the woods, they're going to be kindly and sweet and they're going to give you everything they have. But it turns out that's not true at all. Like if you actually come across people hunting in the woods, they're probably going to kill

and eat you. Like if you actually went back to the CRO Magnon Neanderthal period, even a lot of the Native Americans seem to have done this. Like there's a lot of attempt to minimize it. They're dozens of digs or construction workers have come across bones that are like perked and cracked for Morrow. And some on my understanding is that they're generally encouraged to bury these, which is not at all the usual

practice. So they don't, you know, contribute to the spreading of false narratives about our innocent indigenous brethren. But so at any rate, when the Whites came to the New World, what they found was a complex mix of societies at varying levels of sophistication. Some, like the Aztecs and Inkos, were as sophisticated as the Whites, just at a lower level of technology, stone and copper as

opposed to iron based tech. Others were sizable tribes like the Mississippians. Some were isolated bands of hunters. Some of them were particularly kindly. I mean, a typical group would be the Iroquois, which were, you know, well developed people, roughly equal roles for men and women, but which legendary

warriors? And they gave the world the Mohawk, they gave the US special forces, from what I've heard, the idea of wolf warrior raiding, you attacked just before the crack of dawn and very small parties. I mean, they, they were along with the Scots, Irish for some of the people to bring scalping to the world. So like the idea that these people got off a boat and they encountered these innocent naked people who started bringing them gifts of corn and beer and bowing down and so on.

No, the first people that have come from encountered were Chief Massas White's warriors who had long bows and were coming out of the woods and regimented formation with deer skins over their shoulders. And so they're just humans. I think it's a good way to look at it. The natives were no better or worse than anybody else. They were skilled warriors and good narrators, and they fought off the Whites for 400 years. I mean, that's really it. They were no better or worse than anybody else.

But presenting them as sort of peaceful Eloy actually implies they were better or worse. They were a different breed of man, and that's not correct. There are no different breeds of man. Same thing in black Africa, by the way, which I think is where Peter Griffin was actually supposed to be with the Afro on his head and the bone in his nose. Neither of which was an African style, by the way, but I mean like the idea that the whites went to Africa and started throwing Nets over people.

Like they just showed up in Zulu land with a rope and like grabbed a couple warriors and nothing happened because they were white is obviously fantastically nonsensical. What what actually happened in the African slave trade is there was a long running African slave trade run by the West African kingdoms that are today Ghana and Nigeria. Other like bricks level countries and the black Africans were more than willing to sell slaves to the Arabs who had been

their old friends slash enemies. And when the whites entered this long term market that was run by Ashanti Banan, again, trees that were certainly on par with some of the countries in Eastern Europe, the blacks sold to the whites too. That's it. What do you think about that disease environment in Africa where you've got the what are the Titsi flies that'll kill a horse? You know, you have the malarial and dingue fevers and so on in

the center of the country. I would bet that the life expectancy of a Caucasian fighting man in Africa would be measured in weeks. It would be like an African attempting to raid into the Viking country there. That just didn't happen. So no, the whites would pull up along shore in a boat with a bunch of dangerous guys on it with guns. And they'd be met at the shore by a bunch of dangerous guys with guns and bows. And the two groups would shake hands and get drunk together.

And eventually someone would bring a cough full of slaves down to the beach and they'd negotiate price and the slaves be loaded on a boat. And this sounds horrible to us, but this was the institution of slavery around the world. Who were the slaves? I mean, they were people who'd been defeated by, say, King Gezo in war throughout most of history. If you lost a battle, you were loaded on a ship, and you were given an unwelcome chance to develop your agricultural skills somewhere else.

I mean, there were white galley slaves throughout the Muslim and to some extent black Mediterranean. There were white sexual slaves, something that's minimized for obvious reasons today. Throughout the Arabic harems, blondes were in high demand. There were black agricultural slaves in the Arab world. There were black slave warriors, there were white slave warriors, the Janissaries. I mean, at the time there was a significant price for defeat.

You mention a book, Larry Kroger's Black slave owners free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 17921860. So when we look at the historical record, we see slavery going back to ancient Mesopotamia, crosses races, crosses continents. What the lesson that I learned from slavery was don't even be a little racist because it could lead to really bad things, worse of them being enslavement.

So if don't be racist isn't the primary message we could learn from slavery, what is the message we could learn from The idea that some people owning other people took place for 1000 years and was really evil, but there wasn't much pushback until recently. What's the great lesson from history we can learn? Well, I mean, I think one lesson we can learn, if you want to be a bit cynical and amoral, is that rules aren't real. Slavery existed for almost all

of history. No one really objected to it because people just don't feel much of anything for defeated enemies. And finally, within the context of a particular religious frame, we said this is wrong. And now most people, including me and you have been raised with the kind of, you know, sort of philosophical training that causes us to most of the time think this is wrong. But the idea that there are definite moral standards that you would hold to in any historical era is almost

certainly not true. I mean, like the idea that you would think of only fans is acceptable if you've been raised in any other historical era or factory farming or the existence of nuclear sun bombs or something like that, that that's simply not accurate. And in reverse, the idea that you would be utterly concerned about some captured been a night warrior who's outside harvesting your cotton. I mean that that's almost certainly not true.

So I mean, I think that what can we learn from slavery? I mean, it's important to give, you know, some kind of moral indoctrination to kids early on. The the basic idea of slavery is so that I guess that's actually the point I had to teach kids what we think is good early on, recognize that humans are capable of a large number of things that we today consider evil. You know, I think that's a

valuable point. The, the basic thing that I think people should take from my discussion of slavery in the book, as you kind of pointed out, is that slavery is actually not a particularly race linked practice at all. So every race has engaged in the practice of slavery. Slave is one of the 1st 20 or so human words. I mean, if you go back to those primeval cinea form languages in Babylon and before that in Ur and Uruk and so on, I mean the word slave literally just means defeated warrior.

It's a slave. The symbol for slaves, the symbol for man from the mountain cities. But it's been changed a bit. The editing actually looks a bit like a shackle. You know, So it's just, it means, like, you came down here and you fought the plain cities and you lost. And from that point forward to Greece, through Rome, through Arabia, through Thailand. I mean, you've seen slavery in practice now.

I mean, there are obviously people who specialize more in this branch of social science than I do that I'm sure will have all kind of technical critiques. Like, you know, Riley didn't know that American slavery is specifically racialized. But one of the things about being a smart generalist is that I don't necessarily understand why that's supposed to matter. Like, the argument is that, well, we in the USA, we had slaves that were almost entirely members of one race. Well, yeah.

But I mean, the Islamic rule is that you can't enslave members of your own religion. So all the slaves were Christians and Jews or pagans. And I mean, in at the time, conversion was almost impossible. I mean, you couldn't, your family presumably would kill you if you're a Christian. And you just say, well, I'm a Muslim now, you guys keep, you know, howling those plants out there. So I mean, why would why would slavery based on religion be less offensive than slavery

based on race? I'm not quite sure. I would actually also argue that the Arab trade incorporated the idea of slavery based on race. The Arabs gave the world both commonly used terms for slaves. So a Slav, a Slav is a Southern European, often a white blonde. That Southern Europe, southern Eastern Europe has traditionally been a very poor region of the

world. I mean, you're talking about Bosnia, Macedonia, Albania, Kosovo, a lot of it's on par with many areas of Africa today in terms of rate of conflict over the past century and so on. Slav referred to became the term for slave, the denim for slave, and it referred to people from there. And that generally meant a white slave. There's also a term avid, which refers to an African and which generally came to mean a black

slave. It's used as a derogatory term for blacks in the Arab world today. So I mean, the Arabs were definitely aware and they believed that they were suited for different things like agricultural work outdoors in the Arabic lands was seen as more appropriate for blacks or for captured Muslims and for whites. And you can understand for genetic reasons why that would be the case.

So a lot of this seems like a very technical attempt to find fault with the West when you get into these details like, well, we were the only country that held black slaves in the New World. Well, yeah, because you had to find the New World. I mean, there, I don't see that slavery was very different in any of its forms globally. In fact, last line there seemed to have been.

There don't seem to have been. There were elements of traditional slavery that were far harsher than anything that we engaged in in North America, as horrible as our practices were. I mean, the ancient Romans held full on gladiatorial games where slave men and women were pitted against like chimpanzees, tigers, You know, they would dress you in these ornate military outfits from ancient societies and put you in the Colosseum, in a boat, in a sea

full of crocodiles. You know, that was the the penalty of capture by the Romans. I mean, you know, and this this sort of thing went on and on through the eras. The Arabs would regularly surgically modify captured white and black fighters. You know, cutting off someone's penis was very common. If you're a role you might play would be being a eunuch harem guard. So the, the key thing about slavery is that you are owned by someone else who can use you as

they see fit. And that is something that's existed for all of human history. What to take from that? It's universal prevalence, how simple it is to fall into, and I suppose the idea that we should train people to guard against the desire to do this, which is very, very prevalent among humans. The book is Lies My Liberal Teacher Told Me. I was just blown away by pages 110 through 120 where you discuss lynching. So two things. One, was there a gender lynching gap when it comes to victims?

And also what is often Lee omitted by the general lynching narratives. Whites lynched blacks because of their race or for so much as talking to a white person. Yeah, I mean that. Well, first of all, that's a fair description. There were a lot of purely racially motivated lynchings where someone would be hanged for eyeball and or something like that. But it's also worth noting that that's not the normal description of lynching in the USA.

So lynching in the USA has been a point of focus because there was a racial element to it. But one of the things that I note in the book is that again, history sucked to use one of the the tag lines for the text, like the things that we take for granted today, like a functioning police state in the positive sense didn't exist for most of time.

So the basic idea of a posse like a group of citizens going after a rapist and beating him and then hanging him from a tree, that existed in almost all societies. If you Google lynching in Kenya today, for example, you'll find that there's a strong lynch tradition there. That's how thieves and so on are often dealt with in isolated villages. And that existed in the USA both in states where there were black people and in states where there

weren't. And speaking frankly, many of the people who were lynched were guilty. That's something that's almost always removed, particularly among the whites. That's something that's almost always removed from these narratives. So in the United States over, I guess all time would be the period. There were about 5000 lynchings, of which a bit more than 3000 involved a black victim and somewhat less than 2000 involved a white victim.

There were 23 states in which more whites were lynched than blacks. So I mean, I make the point that again, there's there's no excuse for a great deal of the extreme racialized violence in the South. But even if you removed that, there'd be a the majority of the, the lynchings would still have occurred. And so I talked about the actual environment in which this

occurred. There were also probably at least another thousand lynchings involving Hispanic and Native American criminals and or victims, which aren't counted in the University of Missouri Kansas City stats, which are just whites and blacks. So I mean, you probably have 3000 plus black guys, 1500 or more white guys when you add in some French cases that aren't in those stats.

And then 1000 or so Hispanics and natives, Native American atrocities against natives are very, very hard to document. So that is, that is a guess. But I mean, the official figures, majority black been over 5000. But at any rate, I mean, so I talk about the context in which this occurred, which is, you know, you, you don't have organized law in a lot of places. You have, I mean, one judge who kind of rides the circuit for a county that in those days was often say 1/5 the size of a

state. Even where you do have organized law, you don't have the sort of professional, we would say post P list policing that we do today. So it wasn't infrequent for mobs to take over large chunks of cities and to, for example, commit extrajudicial executions, which at root is what a lynching is.

So there's a discussion in the chapter of the largest lynching in American history, which occurred in New Orleans and involved 11, I believe, Italian American victims following the murder of a popular police chief in that city. I mean, essentially, a crowd of young men gathered together, got drunk, stormed the city Armory and was able to take out the very small police detachment that was there. Some of them were probably in on it. They armed themselves with rifles.

Then they stormed the jail and in a battle took over the jail, took out the Italian American men that were in the jail and shot or hanged them. And that that sort of thing went on pretty frequently. It was a book, Lynching Beyond Dixie that goes through sort of the cowboy cases in the Wild West. So I talk about lynching. I, I obviously discuss the extreme racism of some of the Southern lynchings. Then I discuss other southern

lynchings of blacks and whites. And then I expand outward to the 23 states where most of the lynchings had nothing to do with racism and there were often as many lynchings. And I make this sort of point about, again, civilization kind of rising up against this older way, which was that if law enforcement is incompetent, you're just going to have a mob that starts killing people. And I describe this as kind of the progression towards civilization that we've seen

over time. And I give other examples in that chapter. I mean, we were hanging people publicly until the 1960s. So, I mean, it wasn't, it wasn't uncommon for much of American history for there to be like a public hanging on the town green. So, you know, you'd have a dance and you'd have a ball game.

And then at the same time, like in front of the courthouse, you know, you'd kill someone who was publicly disliked in town and people would walk by and spit on the corpse and take pictures with it. You know, and this whipping was legal for most of American history. Most people whipped were also vital. I'm sure they were disproportionately black. You could whip soldiers and sailor men. And, you know, so all this is discussed and broken down. And I, I explained why we've moved past this.

But there's also an undertone of we need to understand that at any point, if the core kind of judicial enforcement apparatus in society doesn't work, this is what we're going to return to, because it's extremely natural for humans. Moving closer to the present, it's commonly accepted by liberals that poverty causes crime. How can we falsify this? Is this something you think is

accurate? Well, no, I mean, I, I think again, again, I'll, I'll often note that some of these things aren't my primary specialty, but I mean, I'm a, teach stats at a State University. I'm pretty familiar with how to read the tables in these papers. I would say looking at the actual relationship causally, crime causes poverty more than the reverse. How would you look at whether

poverty causes crime? And the simplest way to do it would be that you would look at whether within one country, as wealth has increased, crime has decreased. And I don't think anyone even really tries to argue that in the United States. You can also look at whether the poorer states, probably put North Dakota or West Virginia up there, have higher crime rates than wealthier areas, Washington, DC or Maryland centered on Baltimore or

something like that. And obviously what you find is that poverty alone is not a primary predictor of crime demographics. Do you have a lot of young people, a lot of males? African American crime rates 2.4 times the white crime rate right now do are much more significant. Even things like the gun laws, which can deter or increase crime depending on how they're enforced, more significant predictors.

But just returning to that, first one of you can look at income tracked against crime over time. I mean, we just went through the the well known disaster center graphics where you look at the 1950s or the 1960s and you see, well, the entire country there are 8000 murders. And in the 1990s following Reagan's boom years, there are 24,500 murders. I mean, that makes it very difficult to say that crime is a downstream result of poverty.

These are just people that are, you know, trying what's that they're trying to get bread for their families and these sort of like popular leftist explanations. So no, I don't, I don't really find a lot of evidence of that at all, that there's probably some effect of poverty on property crime. I mean, that's the that's the impression that I get from the studies. But no, I don't, I don't think poverty is a primary driver of gang violence by year or something like that.

Yeah, that's the what I actually do find. In fact, when I said I think the causal relationship goes more in the other direction in the white flight in poverty chapters, what I saw was not in fact, desperate people rioting. Yeah, I what I didn't see was businesses leaving and then

desperate people rioting. When I looked at, say, Watts, LA, Detroit, the Martin Luther King riots, kind of separating the, the big incidents from common crime maybe, but I, I didn't see that in any of eight or nine cases. What I actually saw was people rioting, often almost for fun or out of a sense of rage, or blacks just aren't being treated well enough for something like that. And then businesses leaving in mass. And we also saw that during Black Lives Matter.

So it the relationship is the exact is tracks exactly in the opposite direction of what is often said. I mean, in Detroit in the mid 1960s, you had one of the most integrated, best run business communities in the upper Midwest. You had very successful black and white shop owners, dozens of them. Then you had a massive riot. I believe 270 businesses were burned. Everybody else left and all of those guys moved to either the middle class black or middle

class white suburbs. So parts of downtown Detroit today still look like bombs hit them. The obvious correlation is that because of the destructive nature of those riots, which killed a large number of people, you now have fewer businesses in those areas. And common crime at a lower level has a very similar effect. I mean, what you're seeing right now in California, Portland, where interestingly enough, almost all the criminals appear to be, you know, blue haired Caucasian kids.

But Seattle, it's a little more diverse. San Francisco, it doesn't really matter what race they are, doesn't, you know, But all these places where people like smashing in the counters of jewelry stores and running out with thousands of dollars worth of merchandise, They're going into Walgreens and steal like 100 boxes of condoms, this sort of thing. I mean, right now we're at kind of stage one of the reaction where everything's locked up.

I travel often to speak, and it's the most annoying thing in the world to shop in these cities. You'll go in and you'll try to get, you know, a bagel. Well, OK, you can probably get that. But if you want any sort of higher end cheese, well, that's behind this screen. OK, I'm going to need some razors. OK, we're going to have to unlock that. What what about, I mean, some scalp gel? OK, well, that's definitely locked up. It's that's considered a black

hair product, you know. OK, what about deodorant? I don't know that's in this case. So I mean, right now we're there, but the ordinary person's not going to shop in that environment. So those businesses are eventually just going to close and then you're going to see people are going to start griping about this being a food desert or a care desert. But that's because you made it one. I mean, you destroyed your neighborhood. So now there's there's nothing that can survive there.

And that's that's the pattern that we see. Chapter 10 you discuss the continuing oppression narrative. I found the best summary of what this narrative is in this book, Tears We Cannot Stop by Michael Eric Dyson. I'll read a brief section. I want you to respond to what your thesis is in chapter 10, please. We think of police who kill us for no good reason as ISIS. That shouldn't surprise you. Cops rain down terror on our heads with relentless fire and make us afraid to walk on the

streets. At any moment, Without warning, a blue clad monster will swoop down on us to snatch our lives from us and say it was because we were selling cigarettes or compact discs, or breathing too much for his comfort, or speaking too abrasively for his taste, or running or standing still, or talking back or silent, or doing as you say or not doing it fast enough. Like all terrorists, they hate

us for who we are. They hate us because of the bad things they and you think we do. Like, breathe, live. That is our sin. Death is our only redemption. What is your response to that worldview by Michael Eric Dyson? Very popular guy. I'm not straw manning anything here. Jesus Christ. I mean, I dislike phrases like whining like a bitch because they're kind of sexist, kind of kind of negative.

But I mean, just like, it's if you listen to this sort of thing, and Mike is apparently a nice guy if you meet him in person, but like, if you listen to this kind of thing, it approaches hysterical. Like so much of modern leftism is the young woman performatively screaming at the sky. I mean, so this guy goes through this whole paragraph of like, will he kill me? The blue clad monster. I hear him approaching. I hear his voice. It, it sounds like BDSM erotica.

I mean the it's just extraordinarily bizarre. My response to that would be, first of all, calm down, take a Valium or something or go to the shooting range. But like, like there actually is a real response other than banter and mockery. And that is that you have to look at risks in context. You know, every single year I think it's 152 people die, men die falling in the bathtub.

The total number of unarmed black men shot by the police last year was 12. So in the the continuing oppression narrative chapter, and I take a couple swipes at the dissident right too, where I point out the total percentage of interracial crime in the USA, black on white plus white on black is like 3% person most likely to kill you is your wife. Everybody needs to calm down. All these guys online, they're sharing videos of like, well, my race won this fight.

Well, no, will you on this one? Like relax, it's not that serious. They're 20 million crimes in a year. The total number of interracial murders last year. Now there are people the data account fentanyl argue it's more than this if you counted multiple offender attacks, depending on how you measure those. But that's according to the FBI. The total number of white murders of blacks last year I think was 300. Black murders of whites was 500.

So I note all this in a lengthy chapter in my book Taboo, which is where I'm getting all these stats from. But I I do most of my swipes at the left because the left is so much worse and more more hysterical with this stuff. So breaking it down kind of point by point, I mean, I respond to Mr. Dyson at chapter length. And the first thing I say is that the Black Lives Matter

narrative is completely insane. The argument that Dyson makes has been made over and over, by the way, I mean, Cherno Biko went on Prime Time Fox and said that roughly every day, it's either every day or every hour, an innocent black man is murdered by the police. So innocent, presumably unarmed, is full on murdered. Then who's that lawyer?

Benjamin Crump wrote an entire book called Open Season, The Genocide of Colored People where he argues that the number I mean for a genocide must be in the 10s of thousands. And he goes through all these ways that black people are being wiped off the planet. Again, if you actually look at police violence in any coherent way, the unarmed total for blacks in a typical year is 10 to 12. Highest year I've ever seen was 25. There's not even much more to say about that.

The total number of black people shot in a typical year by the police is 250. All members of all groups. Together, it's under 1000 out of 60 million police encounters across the entire country. That's it. Those are those are the facts. Interracial crime not only is extraordinarily rare, black people commit 70 to 90% of it in the typical year. I mean, in most interracial crime is robbery. And that's one of the crimes that's dominated by African Americans, just as a statistical

quirk. So like anytime you complain about this tiny fringe thing, be aware that we're responsible for 85% of the tiny fringe thing. Like, so if anyone is complaining about this at all, it shouldn't be blacks. I mean, the the reason that I use the term continuing oppression narrative is that the entire idea here is that the explanation for black struggles today. And this is the same argument that's used, of course, for any group struggles, immigrants, women, members of the LGBT

community. The entire woke argument is just the Marxist argument. Society is structured to oppress me, and all gaps in performance within society indicate that oppression with a few IQ points knocked off. So you see this all across the map. It's not just black people doing it, but continuing oppression narrative is something I see mostly within the context of

race. And the argument within the context of race is that the reason we see these problems in, for example, black communities is ongoing racism in society. Now, when people are challenged to find ongoing racism in society, you know, I come from the business class, at least as an adult. And there obviously are massive affirmative action programs designed to help us out, right. So where, where's the bigotry? Well, it's the police shootings,

but there are only 10 of them. Well, OK, it's you guys attacking us on the street. Well, that never happens. And when it does, we do 80% of it. Well, it's cultural appropriation that doesn't exist. So I just go through this whole chapter about like this, this stuff is not real. Like systemic racism is the final bulwark that I think I get over. It's kind of the final boss.

But I cite the work of this economist, June O'Neill, that actually just takes these performance gaps between blacks and whites and does stuff like a just for IQ. Like she's probably a better methodologist than I am. But it's it's hilariously simple. Like what happens to the income gap between black and white people if you're just for the fact the average black guy's 20 and the average white guy's 50? What happens if you're just for the fact that the average SAT for blacks?

We're getting it up, but it's 950 and for whites, it's 1100. And it's just the simplest, most obvious thing in the world. But when you do that, the gap closes to nothing. And I mean, I've replicated some of this myself because it's not hard to do. I just described the whole model. But when you do that, there is no gap. And it's just obviously you can say, well, more black people are poor because we lost the last

race war. So there are more kids that are going to struggle to get an SAT of 1100. Sure, but that's not racism. And I think the point is that once you point out the actual issue, which is that we have more poor people, so we have lower test scores, we need to get those bad boys up. You're you're left with this whole House of mirrors that we can just move out of the way so we can focus on getting the test scores up or lowering the crime

rate or something. And the continuing oppression narrative is the distraction from doing that. Yeah, the Washington Post article that you cite in here says 95% of people killed by police are male. And when you look at the stats, it is not proof of sexism against men at all when you look at who commits the violent crime. The Washington Post also indicates ageism, that men in their 20s and early 30s are disproportionately killed by police.

It shows nothing about actual ageism If you look at the other side of the equation, which is higher levels of testosterone, more likely to be violent. Do you have a little more time? I just love this book so much. A bunch of things stood out to me. Is that OK? Yeah, like five. I have to get off in probably 5 or 10 more minutes. 5 minutes OK 10 probably 10 minutes 2. 30 I'd

say. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said in a book titled In Retrospect that he had told Johnson to authorize the Gulf of Tonkin resolution after he mistakenly thought an attack took place on August 4th of 1964. This was the resolution that escalated things in the Vietnam War. With regard to your Vietnam War chapter, is your case that it was a justified war or that it was more popular than people think it was? Well, I'm not sure.

So again, I'm, I'm something of an amoralist when it comes to high level political decisions. I mean, I don't think either the USA or the North Vietnamese during the Vietnam conflict behaved in kind of a perfectly ethically forward fashion or anything like that. I mean, the South Vietnamese government was a badly run dictatorship.

But I mean, I think my point about Vietnam, my point about Vietnam was simply that the war was almost certainly winnable and more importantly that it was perceived very differently within the USA than is commonly thought to be the case today. And I guess, I guess that would really be, that's a good question. I guess that's really my point that the the lie is the presentation of the civic

understanding of the war. So the you're talking about chapter four of the book, which is it has some some funny, provocative title, but it's like the hippies were wrong. The sexual revolution was terrible for you feminists and the Vietnam War was winnable and popular. I mean, but I actually think those things are mostly true lies. My liberal teacher told me future classic, but the so the the 60s are something that has been really mythologized to a great extent.

I don't know if this is still the case for you slightly younger guns. But I mean, in my generation, everyone had like the grandma maybe that had been to Woodstock and that marched with King. And this was always discussed in these golden terms. Like, so when did I grow up? I was born in the 80s. Yeah. No, definitely. Like grandma's about 60 constantly. This is John Kerry marching

across the debate stage. You know, my generation said we would change the world and we did, like throwing medals over fences and into the crowd like this. This was the this is the the tenor of the times, like the Copperhead Road and people, the guy went to Vietnam, people

singing about Vietnam today. The idea is always kind of presented in sort of a golden light, like the people making out in the mud at Woodstock, the people burning their bras, the people marching behind the, the black icons in the South, this kind of thing. One of the things I point out in this chapter is that obviously basic black and female civil rights were good but most of the stuff that come out of the 1960s

was absolutely terrible. Like the pro cowardice movement with like young fighting men burning draft cards and people chanting nothing is worth dying for came out of the 1960s and has lost us several conflicts since then. You could argue America hasn't won a major war since except maybe Gulf War one. Although I wouldn't insult our troops by making the strong form of that argument.

But I mean like the anti nuke movement and the eco freako movement which has killed millions of people came out of the 1960s. Like we literally could have a nuclear powered planet now, we don't all that stuff. Black radicalism, like the roots of all the candy nonsense you've been reading this interview that came out of this like Stokely Carmichael, Huey Long, all those guys came out of the 1960s.

The white radical terrorists that often would, you know, fuck and party with the black radical terrorists, many of whom Bill Ayers and so on, are college professors now, by the way. But you know, the weatherman, those boys, they came out of the 1960s. Just all of it. The Manson family, the drug revolution, the hard sex and kink revolution, you know, the first furries were like 1974, man. Like all of this crap came out of the 1960s. And so I make the point like a

lot of this stuff wasn't good. People think it was fun because they were high all the time and it was starting. So like your buddy who was telling you that she sometimes like anal sex, like, OK, who cares? But then is writing books about it and becoming, you know, a housewife and Vice columnist and so on. This is a real person I have in mind here.

Like all of that stuff began in this particular moment and is seen as positive by people that were in that moment, but mostly had a pretty negative downstream effect. The more serious Vietnam component of this. And by the way, with the sexual revolution, I obviously think it's good that both men and women now can enjoy oral sex and so on. But I mean, I, there's a couple pages where I actually talk about STI, which frankly didn't exist before the, the sexual revolution.