¶

I came across this story about a Colombian bishop called Ruben Dario Jaramillo Montoya. He's the Bishop of Buenaventura, the port city on the Pacific coast of Colombia in the Department of Val de Cauca.

¶ The Blessing of Buenaventura

In 2019, during a festival for Saint Bonaventure, Bishop Jaramillo was going to board a military helicopter and fly over the city, pouring holy water down onto the streets of Buenaventura to exercise it. In his own words, he said that we have to drive the devil out of Buenaventura to see if we can restore the peace and tranquility that our city has lost due to so many crimes, acts of corruption, and with so much evil and drug trafficking that invades our port.

Now. Unfortunately, the aerial method never materialized in the end, but I do know that the bishop certainly did travel around on the back of a big red fire truck covered in green and yellow balloons, sirens going and sprinkling holy water onto the streets. He told aci, where blood ran, where blood was shed. We will now pour holy water as a sign of reparation in the place of the dead fallen by violence. The problem is that there is not yet a culture of denunciation because there is fear.

We have a society that is afraid to inform. Bishop Jaramillo is a remarkable guy. Since leading the Diocese of Buenaventura in 2017, he has faced death threats for his campaign against violence, drug trafficking and organized crime. If we Fast forward to 2022. On October 2nd, a sports event was held in the violent neighborhood of Juan 13, called Buenaventura un Paz.

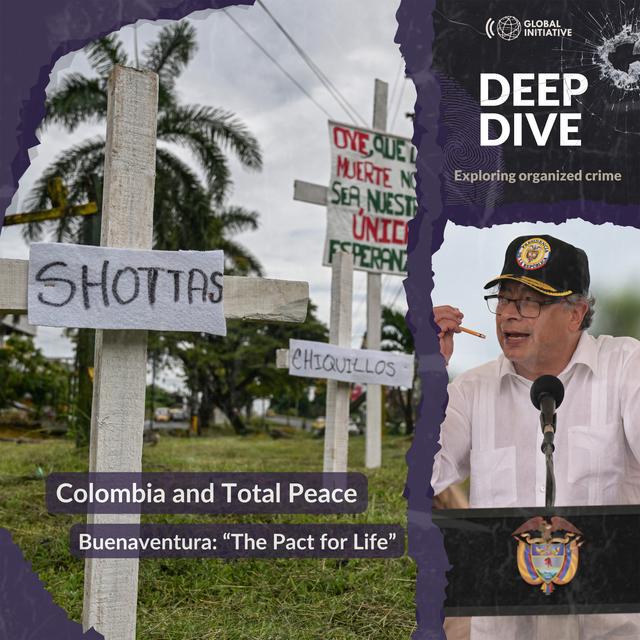

The event was organized by the diocese and led by Bishop Jaramillo, who after two years of extreme violence, mediated a truce between the city's warring gangs, the Shotters and the Spartans. Welcome to Deep Dive from the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. I'm Jack. Megan Vickers and this is Colombia and total Peace Part 2. Buenaventura the Pact for Life.

In the last episode, we focused on the ELN and Arauca and the negotiations with the government under the Total Peace Policy. If you didn't hear that episode, I recommend you go back and give it a listen as it outlines some of the details about what this policy entails. But just to recap, we have these two strands to Total Peace under which these talks can take place. Political criminals like the eln, armed groups that have political ambitions.

But the second strand is negotiations with so called high impact criminal organizations, basically organized crime. And so that's a big part of Total Peace. To think beyond those guerrilla groups and include every single actor who is generating Violence in the country. Here's Felipe Botero Escobar, the head of the Andean Regional office at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, who we also heard from in the last episode.

One of the interesting things about this is that despite the fact that you consider one group as political or purely criminal, all of them has a political nature. Even at the very local context. Those are the ones providing justice, doing policing, actually creating infrastructure. So what makes Total Peace an interesting policy is that this clear differentiation between being a political group and being a criminal group is blurred in Colombia right now.

And all of them are heavily involved with criminal economies, but also leading or delivering certain political aspects. So let's explore the organized crime angle because it gets a little tricky. You see, as part of Total Peace negotiations, criminal organizations must submit to justice, which is basically a disarmament, demobilization and Reintegration process, or DDR.

We've seen similar things like this before, and I'm sure many of you are familiar with the story of Pablo Escobar, so I won't relay the whole thing here, but in the 90s, he agreed to surrender to the government, providing extradition to the US Was off the table. And if he could build his own prison, Le Cathedral. We sort of saw another one of these with the Autodefensus Unidas de Colombia, or auc, who were a right wing paramilitary force led by the infamous Castano brothers, Justicia y Paz.

The AUC demobilized in 2006 after a peace dialogue, but in the end, it was kind of a submission to justice, but with a form of transitional justice included. The leadership of the AUC would serve a minimum of eight years, with lower level combatants being required to engage in a reintegration process. This included sharing their version of events with the Truth Commission and take part in some form of community service, and then a commitment not to reoffend at fear of losing access to benefits.

Now, one part of this process with the AUC that was interesting and could spark concern for those taking part in one of these submissions was that just a few years after the disarmament, 14 AUC leaders were extradited to the U.S. colombian government officials claimed that they had not fulfilled their side of the agreement. Regardless, around 30,000 people were demobilized as part of this agreement.

Although the Autodefensis Gaetanistas de Colombia, or agc, otherwise known as Clandel Golfo, was directly born out of the demobilisation of the auc, we did three episodes on Clandel Golfo a year or two ago. Which goes over the history of this criminal organisation. So fast forward to today and Total Peace.

¶ The Challenges of Total Peace Negotiations

There is a historical precedent about how the government approaches negotiations with criminal organizations, but there is a problem with the framework of Total Peace. Here's Juanita Joran Velez, a lawyer who works for the Crime and Justice Lab, a nonprofit in Colombia. Well, so I would say, like, the big gap is justice. And why is that gap so important? So justice is like the tool you use to transit to peace. In the political negotiations, you can expect to negotiate part of that.

That's actually what happened, for example, with farc. But in fact, they split it in two. They prepare by doing some transformations in the constitutions to allow some specific tools of transitional justice. But then they went to negotiate, and then they went to the Congress again to have a law to be able to implement the transitional justice they designed. But then in the negotiation with organized crime, you don't have such a possibility as to negotiate the procedures.

And we don't have now a clear procedure to the submission, the subjection to law, to organized crime structures. So in that case, of course, that makes very difficult to negotiate because it's not clear what the next step is going to be. So you open a negotiation in which you know you cannot negotiate the justice tools, but you don't have a law either. You see, at the moment, there isn't a specific bit of legislation for talks with criminal organizations.

For example, if a group submits to justice, what comes next is unclear. What will the transitional justice look like? If a criminal actor speaks truthfully about the violence they have committed, how much jail time will they be given? Will they get to keep a percentage of the illicit income they generated? There is a lack of clarity on points like this when negotiating.

Prosecutors do have some options, for example, something called the principle of opportunity, which has to be signed off by a judge. Now, this means that a prosecutor can omit a crime from a prosecution. For example, they might say, we won't prosecute you for the extortion offences you've committed, but we will prosecute you for the drug trafficking. The intention being to help progress the negotiations.

It's the tool you can think can be used, for example, in the case of organized crime, to kind of find a way to advance the submissions, the subjection of criminal organizations to law. But there are some problems. First, it has a lot of limitations.

For example, there are some crimes in which this tool cannot be used, but also there are not clear incentives because, you know, it's a tool that is part of, like the Ordinary criminal prosecution in which you don't have like big, big incentives for people to just decide to submit to law. So incentives are not clear in this case, but the possibility of not prosecuting is what makes this tool, like a very attractive tool to think on how to deal with criminal organizations.

And so this episode is about the negotiations with high impact crime organizations. And for that we need to travel to Buenaventura on Colombia's Pacific coast. So why is Buenaventura important? Well, firstly, the port here has long been incredibly important to the Colombian economy. It manages a huge percentage of Colombia's global shipping trade. The two biggest commodities are coffee and sugar. The largest coffee warehouse in the country is located here. With a capacity for 90,000 sacks.

The port handles 99% of Colombia's sugar exports with storage capacity for over 12,000 metric tons. But it's also a vital node in the international cocaine trafficking ecosystem. It's Colombia's largest port. So around half the commerce of the country moves or goes through the Buenaventura port. So this is clearly a very strategic, important city for the country.

This is Mariana Botero Restrepo, who until recently worked with the GI as an analyst and a researcher in our observatory of the Andean region. It's very close to Cali, one of the main cities which has a history of criminality. And it's very close to some of the hubs with highest criminality in the country. So northern Cauca, for example, where there are many groups, whether criminal or armed groups. Most of the population of Unaventura is from Afro Colombian communities.

And this is important because they often have some specific rules or laws that apply basically only to them. So some sort of specific social and legal organization that they can apply based on their traditional history, customs. But criminality here basically formed around providing services for larger drug organizations. There are two major gangs. One of them is called the Spartanos, or Spartans, and the Nixotas.

¶ The Dark History of Buenaventura

Now I think we need to look at the recent criminal history of Buenaventura to show how the two groups that currently dominate the city, the Shottas and the Spartans, emerged. So let's look at the Shottas and perhaps it's fitting to start with the family behind this group who've been heavily involved with organized crime in the city for a while, the Bustamantes.

Now, back in the late 90s, first there were members of the FARC before switching sides to the Blocke Calima, the Kolyma Bloc, which was a faction within the auc, the Colima Bloc were sent to Buenaventura to dislodge the FARC in the surrounding rural areas.

After the demobilization of the AUC in 2006, which saw groups like the Urobenos, or Clandel Golfo and the Restrojos emerge, the Bustamantes created their own group called La Empresa, or the Company, and took over organized crime in the city of Buenaventura. So things like extortion and also access to the international cocaine markets through the port, but also engaged in a hell of a lot of murders, kidnappings, and disappearances.

According to some estimates, in the first decade of the 2000s, over 1,500 people were murdered in Buenaventura. Now, the violence between the gangs in Buenaventura has been startling, even by the standards of Colombian organized crime. There were a number of wooden shacks with corrugated metal sheet roofs raised on stilts at the edge of the bay. These became known as casa de Pique, or chop shops. Now, I have to warn you that this is not for the squeamish, as these were dubbed houses of horror.

Chop shops were places that the gangs took their victims to torture and dismember them before the body parts were thrown into the sea. There was this one story that particularly caught my eye in El Spectador, and that was of Tatiana Paracuero, known as Sol. It's alleged that she was working for Urbenos Clandel Golfo, but had collaborated with the company. She was tortured, hanged, and her body was hacked to pieces with machetes, all of which was recorded on a cell phone.

Police arrived as the crime scene was being cleaned up and found bloodstains and parts of her dismembered body in the building. Over the next few days, different parts of her body began to wash up on the beach in bags filled with stones. First the right leg, then the left leg, and then four days later, the torso. Five members of the Urobenos clan were charged with the crime of torture, forced disappearance, murder, and conspiracy, including at least one minor. Some say three of the killers were.

Residents often report that they hear the screaming of victims and the pleas for mercy in these chop shops as they were dismembered alive. The residents didn't report this due to the fear of reprisals, and described the fear as absolute. Bishop Jaramillo, speaking to El Tiempo, said that because the gangsters want to kill the people to silence them, so nobody says anything, nobody makes a complaint, because they act in silence, in darkness.

And one of the problems that we have is that the authorities could act, but nobody wants to make a complaint. They Capture a gangster and nobody testifies against him because of the fear. So anybody that complains is condemned to death. They will kill him. That's why making a complaint is practically like a tombstone. It's your death now.

Buenaventura is deeply religious and spiritual, and there are many reports that the dismemberment of bodies has a religious component to it, particularly witchcraft. The Afro Colombian communities make up the majority of the population of Buenaventura, and it has been alleged that this practice is a mix of West African voodoo and Catholicism. Several reports have talked about how when a murdered victim's body is being prepared for burial, a witch ties the fingers and toes together.

Apparently, it helps to get revenge on the murderers. If the name of the murderers is known, that name gets written down and placed inside the body of the victim. A curse that will bring a slow death to the perpetrators. It's said that this is the reason why many bodies are dismembered to prevent this ritual. Some bodies have even been dug up and burned to prevent the curse from becoming reality.

One article in the Telegraph reports how a local witch blesses a local gang member's rosary beads, saying, block their eyes so they don't see me. Tie their hands so they can't catch me. The gang member also wore a shoelace around his torso, which tightens when danger is nearby. He claims that it saved his life when 12 shots were fired at him.

Such was the violence in the city that in 2014, a pamphlet was shoved through the doors of Buenaventuran citizens and was shown to BBC Mundo Cordial Greetings from La Impresa. Through this letter, we addressed the people of Buenaventura to inform them of the the acts of terror and violence that have been happening in the city are not only the work of La Impresa, but also of Los Urbenos. If there are so many homicides and disappearances, it's because we're defending ourselves.

Between 2010 and 2013, Human Rights Watch reported that 13,000 residents fled Buenaventura due to the violence. More than 150 people were reported missing during that same period, twice as many as other parts of Colombia. By 2016, the company was abandoned by the Bustamantes, and instead they formed La Locol. Although remnants of the company now known as Los Cinquillos still operate in the city.

But La Local were the new power, and over the following years, they were estimated to be responsible for 90% of the homicides in Buenaventura. The Bustamantes also contributed to Colombia's unwelcome Reputation as one of the most dangerous places in the world to be. A community leader and activist, Themistocles Mercado sought to protect land rights and urged the government of Colombia to invest in community infrastructure and public services.

But Mercado was killed in January 2018, and it was reportedly ordered by the then leader of La Local, Diego Fernando Bustamante Riascos, known as Optra. Optra rose to lead La Local after his uncle Lugo Bustamante was captured in April 2019. Now Optra is an interesting character. One video from his social media showed him dancing in a swimming pool, clad in expensive gold and diamond jewellery. And another with a questionable zoom in and out repeatedly on what looked like an M4 or an M16 rifle.

The leadership of Optra was controversial even before his own arrest at his farm in Antioquia in 2019, his capture reportedly aided by the digital clues that he'd left on his social media. Unfortunately, Optra was released from prison in 2022. But during Optra's short stint in custody in 2020, the local split into two competing factions, the Shotters and their rivals, the Spartans. And the cycle of violence continued as they battled for control over the city.

This split caused the murder rate to rise again, with a rate of 31.2 per 100,000. And disappearances likewise had seen a significant increase. The Shotters aligned with Clandel Golfo and according to Insight Crime, possibly FARC dissidents. And the Spartans aligned with what was left of the company Los Chinquillos. According to the Colombian government, they estimate that There are around 1,700 people, mostly young people, operating in the two main gangs. In 2020, there were 75 murders.

A year later, in 2021, as these gangs clashed, it rose sharply to one hundred and eighty eight. Such has been the violence that it led to an informal curfew, with residents living in areas with high gang activity, rarely leaving home after 6pm and the establishment of so called invisible borders between neighborhoods.

¶ The Impact of Gang Violence on Buenaventura

If someone from the wrong neighborhood crosses that border, they can wind up murdered. Is Mariana. They have a lot of power in limiting people's ability or right. And I say right like in quotation marks, because they are able to limit the person's or the inhabitants mobility, so they are able to install curfews or to limit who can enter which neighborhood, depending on where they live.

So we would see cases of people who were unable to visit their families because they lived in a neighborhood that was controlled by a rival gang. So in order to meet, I don't know their mom, they would need to meet in the city center. Rather than just being able to visit their families when there is an active dispute, they would limit the times in which people are allowed to enter, to enter the neighborhood.

So let's say, and this is a real case that somebody was telling us about either 11pm or midnight, if your work required you to leave or to enter the neighborhood at that time, you needed to ask for permission or inform them beforehand.

Indeed, this curfew reminds me of this One story from September 2022, where Bishop Jaramillo explained that because of the violence between the Shotters and the Spartans and the curfew imposed, the evening mass in churches across the city had to take place earlier so that worshippers could comply with it. He said they send out a statement that at six in the evening everyone has to be at home, so everyone has to obey. Obviously, this has had a huge impact on those living in buenaventura.

And in 2022, over 6,300 people were displaced from their homes. Another 2,100 were confined within the municipality, many of those within the city itself. It's estimated in total that around 20,000 people have been displaced in the whole of Buenaventura. Some researchers described people living under these gangs as having shadow citizenship. And we'll come to that in a moment, because in our brief narrative history, we've arrived at October 2, 2022 and total peace.

Leading up to this point, the number of murders in the city was 85 by August, actually higher than the previous year at the same point. But as we heard right at the start, Bishop Jaramillo and the Catholic Church alongside the government, was already mediating a ceasefire between the Shotters and the Spartans, eventually agreeing to a truce in September before renewing it in December. It was cited as the first real achievement of Total Peace.

But again, there are rumblings over the approach of Total Peace, the same concerns that arose in relation to the last episode on the ELN Anarauca, and that's the centralized approach to negotiations and a lack of local involvement. When you talk to local authorities about what their role is in Total Peace, one of the main conclusions of one of the reports of this research is that the role of local authorities is very, very reduced.

We even had complaints of authorities saying they're not even being involved in logistical details when people from the national government go. So the risk is that if this process doesn't work, there is no Plan B. And authorities, local authorities often do not even know what's being agreed, or they do not have the Detail, they might find out, you know, communiques and, like, people on the ground.

But there's not a strategic participation of local authorities in the design of the process, in the implementation of the process. And up till now, or up until our research, there wasn't a clear path as to what their role would be if it was successful or if it wasn't. And this is true for local authorities, but also for security forces. And here, remember, we're talking about a city in Buenaventura, and the dynamics are totally different to a rural setting like Arauca.

¶ The Dynamics of Criminal Control in Urban Settings

In the cities, groups tend to be more criminal than political and armed. They exercise control in a different way. So what about the community voices? What say do they have in Total. Peace people in Buenaventura and in most of Colombia, they want peace or at least a real reduction of violence that would allow them to live a better life. The thing is that specifically with Total Peace, the community's participation, especially in Buenaventura, has been very limited.

And when we asked people if they knew what the table or what was being discussed during Total Peace for Buenaventura, if they know what was being discussed, they would say no. Some of the concerns we did hear was that the media attention, which is not a lot, but there is some, was in some way legitimizing criminal groups that were nothing but criminal. And that was a real concern.

Another concern was that in this effort of the groups to portray themselves as legitimate actors at the local level, because they do resolve conflicts, because they do have participation in economies, because, you know, like, they do participate in everyday life because they're trying to portray themselves as legitimate actors. They're starting to get involved in narratives and in requests that they never did before.

We'll come to how the gangs are getting involved with aspects of society they previously had no interest with later. First, I'd like to stay with the reduction of homicides. By the time of Total Peace, homicides were already reducing after the good work and mediation of the bishop and his church and the pact for life. Now, the government saw this truce as an opportunity to negotiate with these groups under Total Peace. Here's Felipe.

So this truce that existed in Buenaventura was the perfect setting or context to actually start promoting these dialogues. However, there are a lot of things in the design and implementation of the policy that has left the pact or the truth in Buenaventura just as a truce and is not moving forward. And there is no clarities from the truce that these two criminal gangs did with what actually the government can offer for them in the future.

And at the same time, having the truce has allowed them to stop fighting and actually increase their criminal governance in the territories, kind of strengthening their position for the same conversations. And this that has happened in Guatemala is a trend that we are seeing across the country and in the different negotiations.

Now this has echoes of what we've heard before in that during a period of negotiations with the government, criminal gangs, like the armed groups we discussed in the last episode, have used Total Peace to actually increase their control over territories. And there are concerns that criminal organizations that have entrenched their positions since Total Peace will, as Mariana said earlier, portray themselves as legitimate actors.

So they can potentially pursue the total peace route of political criminals rather than high impact criminal organizations to improve their negotiating positions as it provides more favorable terms and incentives. Here's Mariana. So there is that concern. And a lot of analysts and people who are criticizing the Total policy are flagging this. And we're seeing this in other cases. In the case of Unaventura, it's very hard for the groups to show themselves as political.

And I think that they know that there's no way they're gonna get that recognition. But what we saw is that they are increasingly getting involved in areas where they didn't before. So some people told us that they were starting to control who could join or who could participate in social programs from the mayor's office, for example, which is something they didn't do before. Or they're asking for food for kids in their neighborhoods, which they didn't do before.

This might be used in favor of the negotiation because it shows the aim for a structure or the aim to or like to use this opportunity to somehow solve some of the needs of the community. But if mishandled, it could backfire. But people are not stupid and know the reality. For example, the Conflict Responses foundation or Core interviewed someone living in an area controlled by the Spartans. They say that they are the ones who take care and that people cooperate and behave well.

They are our protective environment against other groups. But in reality, this is a lie because they are the ones who attract other groups. And of course, this guise of protection is used to justify violence on certain individuals. For example, they claim that a person is working with or is part of an opposing gang, which is punishable by death. And these death sentences are quick to be meted out.

There was one story from a Shotters controlled neighborhood where a girl claimed that she had been raped by a guy who'd recently moved into the area. The Shotters identified the culprit and killed him only for the girl to admit that she'd lied. And yet these cases of sexual violence only apply to those living in the communities, not the gang members themselves, who frequently commit such acts with impunity. And let's be honest, you can't really complain to the gang about their activity.

It, unsurprisingly, doesn't go down very well. The gangs hide their increased control behind the facade of conflict resolution, but really it's about extortion. There are a couple of stories that Cor gathered from Buenaventura. For example, one about a father who got drunk. Some of my dad's parents were going to charge him because he got drunk and started making a fuss when he was drunk with my mom, my brother, my aunt and my grandmother. Then the boss arrived and he said, what's the fight here?

What's all the noise? They are disturbing the peace and quiet of the neighbors. So 1 million pesos. Indeed, if there is a case of domestic violence, which granted, is a horrible thing, if you are accused of that, first it's a fine between 200 and $500. And take into consideration that it's estimated that around 80% of people living in Buenaventura live in poverty or extre poverty. So a fine will also significantly impact the domestic violence victim as well.

If it happens a second time, it's literally a death sentence. Other punishment imposed on people can be things such as forced labor, but most of the time it's fines. Here's Mariana. The first step is that they pay a fine, which depends on the rule that they break. These are often high fines, especially considering the vulnerable context upon which these gangs operate.

But then if it's a repetitive offense or if you've been warned before, then punishment can go from being forcibly displaced to being murdered, or to being disappeared, which is basically you're killed, but you just. The body is never found, which is actually one of the things that has increased as a result or after total peace is being implemented. This is not very systematic and it's more opportunistic and erratic.

But what we did hear about a lot is that after some fines, then the punishment will include different levels of violence. There was another story that came from a resident living in an area under the Spartans control. They said you go to them to settle disputes. For example, someone owes you money and won't repay it. So the gang, of course armed, goes to that person and threatens them. And providing the payment is made, they take a hefty percentage.

So if the gangs are making money from these everyday disputes, where is the incentive to actually prevent these disputes happening in the first place? And let's not kid ourselves. These gangs are not a structured state. They are haphazard and inconsistent with their quote unquote rulings. Even opportunistic in the way they try to squeeze everything out of people. Most punishments come in the way of a fine. So if you break the rule, you need to pay this amount of money.

If you have a dispute with another neighbor, then this is the amount of money you need to pay. But people do not always know what the amount of money they are required to pay is. That's a bit up to the local leader or the circumstance or, you know, whether he woke up in a good mood or in a bad mood that day. Within the groups are specific factions organized to carry out certain illicit tasks.

One such was a violent extortionist faction of the Spartans led by Juvan Stevan Mulatto Ramos, known as Chucky. His group would distribute pamphlets to local businesses that showed the extortion rates that they had to pay if someone refused. A.38 calibre piece of ammunition was left in the establishment as a warning. Chocky was actually arrested in March this year. Other aspects of daily life are also controlled, as we've heard, from access to services, to movement between areas.

And if you are not from the area, you need special dispensation, which of course inevitably comes with strings attached. Even the movement of Bishop Jaramillo was reportedly restricted, preventing him from visiting certain areas under gang control due to his campaign against organized crime and violence. And it's control like this, this criminal governance that has led to the communities living in Buenaventura being described as having shadow citizenship.

¶ The Dynamics of Gang Control in Buenaventura

And that is why the part of Total Peace that aims to reduce acts of violence, particularly homicides, only tells part of the story. Groups being the intelligent, strategic organizations that they are, then they can continue with their everyday operations within certain limits. Because both government and organizations measure homicides from violence. That's the easiest indicator to measure because it's. It's right there. It's obvious. You find a body in the street, you call the police.

The police has to report it, but it doesn't measure. Many other crimes, such as extortion or disappearances, is a very hard crime to measure because a lot of times people do not report the disappearances because they don't trust the police, whether because they have working relationship with the gangs or because they do not have the capacity, they lack the capacity to properly address these crimes, or because there is a rule not to do it and this. Is a very important point.

The murder rate has indeed dropped and that is something the administration will look to celebrate. But in reality, yes, bodies are not being left on the street, which would undermine the narrative around total peace. But disappearances have increased. Here's Felipe. This has been also a historical trend in Buenaventura where to not make a lot of noise. Instead of leaving the body, they just disappear the body and disappear in the body is not a homicide. No, it's he or she is just missing.

But it's still a way how the group can send a message and can, yeah, keep implementing violence. There's this tiny island covered in trees in the middle of the San Antonio estuary, which is the estuary that washes up to the very boardwalk of Buenaventura. It's just a stone's throw away. It's called Isla Pajaros, but locally it goes by another name, Calavera Island, Skull Island.

According to some, there could be more than 1500 bodies of people reported missing on that island and the surrounding waters. So remember, right at the start of this episode, we talked about the history of the criminal groups operating in the city. One of the commanders of the Kolyma Bloc, which was part of the paramilitary AUC Evar Voloza, before his extradition to the us, admitted he had ordered bodies to be thrown into the estuary. And this weirdly brings me to state investment.

We've talked about the importance of the port. Well, currently it has a depth of 13 metres. But to accept the very largest container ships, shipping companies are specifying a depth of 16 metres. And this is something that's been suggested for Buenaventura and is currently underway. But the families of the disappeared are concerned that this will make the recovery of the remains of relatives all but impossible, given what's involved in the dredging process.

Now, sticking with the role of the state, remember in the last episode that Arauca had been neglected for decades from the central authority, which allowed groups like the ELN to entrench themselves and essentially co govern in parts of the department. Well, Buenaventura is a bit different because of its vitally important port.

For example, its newest port called Puerto Aguaduce has international backers like PSA International and ICTSI who see the potential of the port despite the delicate security situation. And the central government have put money into the city despite the existence of the gangs. Here's Felipe.

There is a lot of money from the national government going to Buenaventura, but also very structural corruption logic that makes that none of these investments actually touch the ground and change the life of the people. And with that in mind, there is also a lack of trust in police. And there is a long running problem of corruption within certain areas of Colombian law enforcement. And it's no different in Buenaventura. Here's Mariana. This is no surprise for anyone.

It's often or is very common for security forces to collude with armed groups, with criminal groups, there's an issue of capacity, there's an issue of economic. Security forces are normally not well paid, and working with a gang will allow them to have extra income. Often they come from the same neighborhood or the same background. There aren't enough controls within the organization. So this happens here and everywhere.

There was big news out of Buenaventura after an operation conducted by the National Police of Colombia and the DEA arrested a guy called Ricardo Orozco Bieza, alias El Bendecido. It's alleged that Bendacido managed 80% of the illicit smuggling leaving the two biggest ports in Colombia, Cartagena on the Caribbean coast and Buenaventura. But the investigation revealed by Blue Radio highlighted the level of corruption within the Colombian Tax and Customs National Authority and the police.

Between September 2023 and March 2024, officers and officials ensured the smooth flowing of illicit goods through the port using an encrypted communications application to communicate directly with the smuggling network. They received a bribe from two police officers working directly for the network, which totaled around 900 million Colombian pesos. For this access, that's almost a quarter of a million dollars. As the investigation developed, more and more people had been dragged in.

It resulted in the arrest and the currently pending extradition of Diego Marin, alias Petufo, from Spain back to Colombia. Without going into this guy's life story, which is quite remarkable in and of itself. He's alleged to be a former AUC commander turned money launderer for the Cali cartel and running his own smuggling network.

For years, investigations by El Tiempo highlighted claims by an undercover agent that this smuggling network goes back to the 90s and includes many high ranking government and state officials, law enforcement, senior military, and even a relative of a former president. But it's perhaps worth mentioning that the people have questioned the veracity of this agent, as his house appears to be very large for someone on his apparent salary.

Anyway, my point is that you can see why there is little trust between people and state institutions and forces. Total Peace made it easier for a relationship of collusion between the security forces and the gangs to happen, because Total Peace achieved a truce quite early on in Buenaventura. This obviously reduced the number of direct and openly violent acts committed by the gangs. And then the police with less bodies in the street, had time to do other things.

But one of the hypotheses he has is that the relationship changed with one of the gangs from collusion to competitions. So basically, for the Espartanos, the Spartans, this relationship shifted and this had an effect in the capacity they have to actually have criminal governance in the territories that they used to control.

Whereas for the CEOTAs who maintained or who kept a relationship of collusion, it was easier for them to maintain the criminal governance over the city or the neighborhoods they controlled.

¶ The Complex Dynamics of Violence and Governance in Buenaventura

Because one of the key factors that would allow for armed governance to strengthen is how the security forces react to that control or that power of a group over a population. So we cannot say for sure that's what happened. But this is what people told us they're seeing, this is what they believe, and this is what the number of captures of high ranking people or mid ranking people from the Spartans versus those of the Scotas led us to believe.

Indeed, this year saw the arrest of Scolo Vice, the alleged leader of the Spartans, and also Cholo, a senior leader in the Shotters, was also arrested. So what about local government? Well, there was a quote from Bishop Jaramillo that I thought was quite illuminating. He was asked the question by El Tiempo, what has been the hardest thing about your work in Buenaventura?

And he responded with, the hardest is seeing the government's impotence in controlling the region, seeing that the government is not here, the authorities are not here, governing is not here. One would like to see the mayor taking charge, making decisions. And you see them so tied up, so kidnapped by the criminal gangs. It's as if they want to do things, but they can't because of those other dark forces won't let them. In Buenaventura, Total Peace has reduced the homicides, as we've heard.

Indeed, in November it was announced that the Shotters and Spartans had agreed to extend their truce until February 2020. But total peace has also allowed the gangs to entrench themselves, extending their brutal, constraining and parasitic control over the lives of people in Buenaventura as they tax and extort everything, whether it's illegal or not, and enact violent repercussions on anyone who steps out of line.

¶ Local Governance and Total Peace

So what needs to happen to improve Total Peace? Here's Felipe. First, we need to finalize the institutional framework for Total Peace. Second, we should go in a more strategic and prioritized way? Are we going to prioritize a specific group? Are we going to prioritize a specific region of the country? Are we going to prioritize super local dialogues? Are we going to prioritize urban gangs to diminish violence? What's the strategy that we want to pursue through total peace?

Because having a very broad total peace is clearly creating a cacophony of negotiation with not necessarily specific outcomes that the government can use as an early victory to show that this innovative approach is worth it, to be continued after the end of the government. And finally, I think that there is a need to include more local voices in the conversation. I think that the fragmentation of the Colombia conflict right now happens and occurs in the very local level.

This is not anymore a very national war with national actors besides ELN and Glandel Golfo. But even within those two actors, their local structures are the ones who are acting politically. And I put this under quotes in this local region. So probably going deeper to a more granular understanding and granular conversations can take us to bigger or better national results. Colombia has achieved success with previous DDR processes.

We heard in the previous episode that the vast majority of FARC combatants have remained outside of criminality since 2016. But as we also heard in the previous episode about the political criminals, there are concerns about the middle ranks. It's the same with organized criminal groups. They have the skills and the knowledge. And if there are submissions to justice, then providing the illicit market still exist, then there will be a demand for that knowledge.

And so realistically, and we're talking years from now, what does success look like for total peace? Here's Juanita. While the markets that fuel the war in Colombia are still international illegally, we will need to concentrate on having a better life in Colombia, you know, in having a less violent life, because we cannot solve the problem of international market of drugs. We cannot do it.

So while we are in this scenario, I would say that living a life providing a life without violence for those that live in the territories which are right now extremely violent, that can be a success. But we need to think in a more complex pattern of violence. Not only a life without homicide, but a life without gender violence, without extortions, without kidnappings and so on. That's it for this episode of Deep Dive.

I'd like to thank Mariana, Juanita and Felipe for speaking to me on this episode. There is a reading list in the summary to this show, as well as a link to our Andean office here at the GI which covers Colombia for other research on organized crime from around the world. Head over to our website, globalinitiative. Net. And this has been Deep Dive from the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime. I'm Jack. Megan Vickers. Thanks for listening.