Pushkin, you cannot imagine a more tense, pressure packed moment with all of that at stake, and saying, mister Chief Justice, may have pleased the court and starting your argument.

You understand and respect the roles that the lawyer on the other side.

Is playing, but you weren't convinced by their case.

I was not convinced by their case. I was not convinced by their case. Then I'm not convinced by their case.

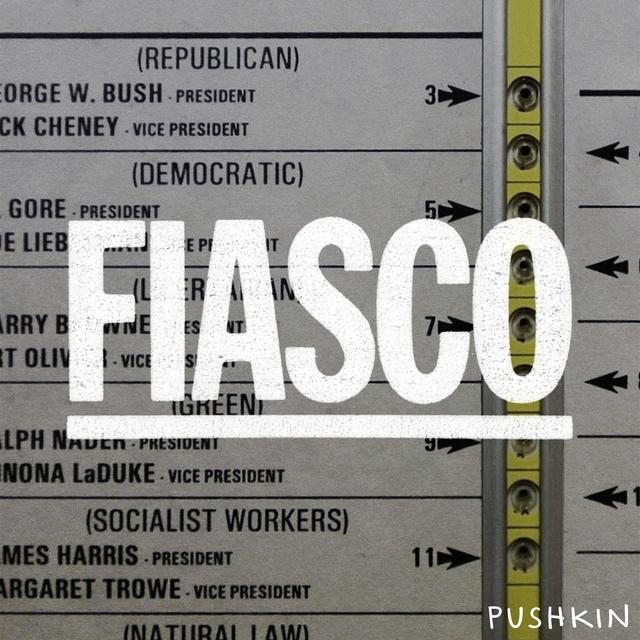

Now, hey, fiasco listeners. Today, in the fifth bonus episode of our series on the two thousand election, you'll hear my conversation with two of the highest profile lawyers involved in the saga of Bush v. Gore, David Boyse and Ted Olsen. You'll hear what it was like to make the case for both sides, from having to quickly catch up on Florida election law, to getting nervous before Supreme Court oral arguments, to even befriending your opposition. We'll start

with David boys. When Boys got the call to come down to Florida, he was fresh off of arguing on behalf of the government against Microsoft in a high profile antitrust case, and he was working on a licensing lawsuit in which he was representing Calvin Klein. I asked boys why he was willing to drop everything and represent al Gore in the recount.

If I hadn't been a lawyer, I would have been a high school American history teaching like my father was, and to have an opportunity to participate in what was Even at that stage, we didn't know how important the case was going to be. But even at that stage, we knew it was an important case. We knew it was a case that was going to involve historic decisions. And to have an opportunity to have a front row seat and maybe even be a participant with something that

would have been hard to turn down. In addition, I'd been involved in a few electoral contests before, and democracy depends on votes being counted and the will of the people being expressed. You can suppress democracy in lots of ways, and we suppressed democracy in lots of ways in this country. But you can also suppress democracy after the votes are been cast by not counting them fairly and not counting

them accurately. And so the process by which votes are counted is a critical part of the implementation of democracy, and I thought that this was going to be something that was going to be essential to people's confidence in our democratic process, and also not put too fine a point on it, making sure that the person who actually won the election occupied the White House?

Did did you have a firm feeling at that point that you know two days out from election day that Gore was the winner?

Not really when I was called, And indeed for the first several days and maybe most of the time that I was in Florida, I didn't really know who won Florida. It was simply too close to call. All I knew is that it was a statistical tie. And what was going to be critical, I thought, to a fair election, but also to the people's confidence in our electoral process that the votes actually be counted the way they were cast. And I didn't know who was going to win that.

I just knew that it was important that that that happened,

and that happened in an organized way. The first time that I really became convinced that Gore had won was actually the Saturday when they stopped the vote counting, because during the course of the previous Friday and Saturday morning, the votes had begun to come in, and you could tell that they were discovering lots of votes predominantly, not overwhelmingly, but still a majority favoring Gore, and so the margin was already disappearing at the time that the Supreme Court

prematurely stopped the vote count.

So tell me what it was like when you got down there. You flew from white planes, right.

I flew from white planes. And I got down there about midnight. Because this all happened the first day I was called, they didn't get through to me until about five o'clock in the afternoon. I finished up what I was doing, got my son Jonathan to pull some cases on Florida election law so I could read it on the plane for the first time ever, read the Florida Statute as well, and arrived down there shortly before midnight. Went to the campaign headquarters in Tallahassee, and everybody was

still there. I remember what walked in and ron Klain saw a man said, welcome to.

Guatemala, referring to Florida. In Florida, if ron Klain was trying to tell boys that he just landed in a legal jungle, he was right, But at least he wasn't completely alone there. As the major lawsuits wound their way through the Florida courts. David Boys became pals with one of his counterparts on the bush side, Barry Richard, and why not they were going through the same thing.

We were clearly in the middle of the Madge spectacle. People walked with you, cameras walked with you, every place you went. Everybody trying to get you to say something about what was going on.

Was it most of the reporters coming up to you in Tallahassee streets or was it normal people who just seen your face on TV?

It was both, But I remember, you know, people driving by and shouting things out either depending on what their point of view was. Everybody recognized Barry Richards and myself, and so somebody was always yelling out to you, either encouraging you or trying to discourage you. It was a It was very much a participatory spot.

But you guys were often walking together, right, and.

Were often walking together, and sometimes they would be showing the same things that both of us. We were walking together, and wow, we didn't really know each other prior to the contest. We became good friends during the contest.

Where did you guys spend time together? Was there places in Tallahassee.

There was a sports bar sort of kitty corner across the street from where I was staying. I was staying at the Governor's End, and there was a sports bar close by where we would go for either a drink or a meal.

I think treat to non lawyers, this is like, this is this is counterintuitive, right, the idea of two lawyers on the opposite sides of of a case being able to come together like this, And I feel like the missing the thing that they're missing is that you guys found this fun, right, You found an intellectual stimulating It.

Was intellectually stimulating. It was we both thought we were doing important work, and we both recognized that our role in the process was to present and argue for a particular side. Sometimes people who aren't lawyers confuse the lawyer with a client, and they think that the lawyer has got to be as angry as the lawyer on the other side as the client is angry at the client on the other side. And when that happens, our justice system begins to erode.

But I have to say, like you had clearly had a personal investment in the outcome. I mean not because you wanted go to win, or you wanted whatever, but because you believed you were right, you believed you had

you're right. So I mean, I'm curious, like, even just during the Sauls triler, during the sord of Spooing court hearings, when you're in the courtroom across from Barry Richard, your pal, how do you sort of balance the sense of intellectual gamesmanship, the sense that you're like in the super Bowl, from the stakes and the stress of possibly losing to this other guy.

There's no doubt that in any important case the lawyer becomes very closely identified with a client, you usually come to believe your client is right, even if you didn't start off feeling that way. But particularly in a case like this, where I felt not only was my client right, but that I felt that the principles that we're fighting for were terribly important principles for our country, you inevitably

become personally involved in the matter. At the same time, you understand and respect the role that the lawyer on the other side is playing. And everybody is entitled to a effective presentation by their lawyer. Our justice system depends on it. And so even though I was absolutely convinced that Gore was right. I still respected the role that

Barry Richard was playing. So you can fight very hard and feel even emotional about your cause, and yet at the same time respect and even admire the people on the other side that are presenting.

Their client's case, but you weren't convinced by their case.

I was not convinced by the case. I was not convinced by their case. Then I'm not convinced by their case now.

So that was David Boyd's who argued the Gore campaign's case in two thousand. Another lawyer Boys respected and admired, but whose case he was not convinced by, was Ted Olsen. If hearing Boys's name next to Olson's rings a bell, it might be because they actually teamed up in twenty thirteen to sue California over Proposition eight, the state's ban

on gay marriage. But back in two thousand, ted Olsen was working for the Bush campaign and getting ready to make his argument before the US Supreme Court after the break my interview with Olsen. By the time ted Olsen was working for the Bush campaign, he had already argued fifteen cases before the Supreme Court, for most of them he had prepared for months, but Bush v. Gore was different. As Olsen explained during our interview, he didn't have months

or even weeks to get ready for this. He only had one day.

You don't have time to do all of the things that you would like to do. If you're preparing for a Supreme Court argument, you like to have moot courts, which are preparation sessions, practice sessions with other people asking you questions, interrupting you the way the justices do. You might want to spend more time doing research when you're

having to do it all in twenty four hours. The Florida Supreme Court decision on that Friday came down at four or five o'clock in the afternoon, and we filed our papers in the Supreme Court I think by nine o'clock Friday night, and then the Supreme Court stayed the recount and granted the hearing on Saturday. So we had

to do all this under enormous time pressure. Obviously, you can't do everything you want to do, but you have a team of very conscientious people, and I'm speaking for the other side as well, trying to do the very very best that you can. Hope that you haven't overlooked something.

Tell me about the morning you know. I know this is I always find when I'm talking to lawyers who sort of mostly live in the world of ideas and arguments, they always rist a little bit when I ask these kinds of questions. But I wonder if you could just take me back to the morning of the arguments a little bit. What do you remember about the atmosphere in the courtroom? You know, how it was different from other Supreme Court cases you'd argued based on just how it felt to be in there.

Well, it was a remarkable experience because the entire world was watching. The Supreme Court was surrounded by the satellite trucks of the various broadcast networks. The court was filled with political figures, members of the United States Senate campaign representatives from both sides, journalists, people of interest, anybody who could get into that courtroom and managed to get into that courtroom. And it's the presidency of the United States.

Everyone was watching. They were broadcasting, and which was a step forward for the Supreme Court. They were broadcasting the audio of the arguments. The moment that we finished, they were immediately sending the audio out to the rest of the world, and people all over the world were watching and listening. Verius television networks were going to be broadcasting it with drawings because the cameras aren't permitted in the

courtroom of the various individuals and the justices. You cannot imagine a more tense, pressure packed moment than standing up in front of the all of those people and the nine justices, with all of that at stake, and saying, mister Chief Justice, may it pleased the Court and starting your argument, and I think all of us fell for God's sakes. I hope I can get these words out without stumbling or forgetting what I am, or forgetting who

I am, or forgetting what the arguments are. One of the lawyers made a mistake three times, I think he did, called the justices by the wrong name. That sort of thing you can happen, but you have to keep your wits about you or you shouldn't be there.

To the aspiring Supreme Court petitioners in our listenership, do you have any psychological things that you do when you're in that situation to try to keep yourself focused and try not to try to say something that's the opposite of what you mean.

Well, your adrenaline is going to be pumping through you. So anybody says, are you nervous, of course you're nervous. And if you're not nervous, you're not a sentient human being or a lawyer. So you have to channel that adrenaline, that energy that's pumping through you into the context and the substance of what you're saying the arguments. You have to focus on what you're saying. You have to focus on what the justices are saying when they interrupt you,

and they interrupt you constantly. I've had sixty to seventy interruptions in the course of a half an hour. So you have to pay attention to what you're doing, and it kind of helps. You've read about football players that the order back becomes a little bit more effective after he's been hit for the first time because then he's you know, focused on the game and so forth. But

that's somewhat similar in court. And I also tell lawyers, you know, take a look at all those people up back in the courtroom watching you, and the clerks and the journalists and the spectators and so forth, and if you'd rather be with them watching, then that's where you should be, But if you'd rather be up there doing it, then take a deep breath, enjoy it, and appreciate the fact that you've been given an opportunity to participate in an argument, and in this case, a very important argument

in a very very important case. So in a sense, it's necessary to relax a little bit to the extent that you can and focus on what it is that you're hearing and what it is that you're saying.

If you were taking beta blockers, no, I tried them once before a live show. It was quite effective.

I thought, well, I'm at a point in my career where I'm probably not going to change whatever my style Old dogs, new trips kind of thing. Right.

You obviously came in with a deep, deep understanding of every justice's judicial philosophy, ideological inclinations. Who were the justices you were talking to most directly during your arguments. Convince.

What I tell myself and tell my colleagues when we're doing this sort of thing is don't take any justice for granted, and don't assume that you're going to lose any of the justices. Try to make arguments that if you were on one side or another in this case of the political spectrum, and I've been in various different contexts in the Supreme Court. Try to make arguments that are rational and coherent and that are respect that any justice could say, well, I understand the logic of that.

That doesn't mean you're going to win them over, but that means you've got to listen to them. You've got to treat their questions with respect. You can't be dismissive. You can't ignore the questions from a justice that seems hostile. And you can't take for granted that what sounds like a friendly question isn't some kind of a trap, either an intentional trap. No, it does happen. It can be

a trap. Or you can say something because you're the justice that you're talking to at that particular moment may be asking you something and you want to agree with what that justice is asking you, or the sense of that justice's question. But the impact of your answer on the other justices and the other votes you have to think about that. So you can't take anything for granted. You have to listen to them. They are the persons who are going to decide this, and you have to

treat them. And of course it makes sense, and it's sort of common sense. You have to treat them with respect and listen to them. But it's hard to do because you're getting questions from all different directions and there's very very little time, and all of us at that point, we've been under pressure for thirty five days or so, and we've been back and forth to Tallahassee on airplanes

and not. The airplanes are not I was on time, and you know, things go wrong, but you've got to keep your feet on the ground and your head on your shoulders.

How did you feel walking out of the courtroom. Did you feel like the questions indicated that you were in good shape.

I never take it for granted when I walk out of the courtroom, all I could. In the first place, you're exhausted, and the second place, you're relieved that it's over. In the third place, I did feel that we had made our arguments, that we were making cojin arguments, and that I thought we were doing better on that count than the other side. But I wasn't assuming that we

were going to win. I wasn't relieved, and I never felt that we had at one And I think along with everybody in the world, I didn't know until they called me up at ten o'clock on December twelve and.

Told us, do you remember who called you?

There were various different clerks working that night, and General Suitor sut are different than Justice. Suitor had each one of his assistants call one of the lawyers for each of the parties, got us all on the phone, so nobody heard anything until we were all on the phone and then read the outcome at the same time. So we were all getting information at the same time, very bare bones information. There is a decision from the cars. There's the parality decision, there's a there's a there's a

per curium decision. There's a dissenting opinion by Justice Stevens, joined by Justices so and so and so and so and so on forth, dessenting opinion by Justice Ginsburg, joined by so and so on, and you had to sort of infer what the outcome was. It was helpful that the four liberal justices who had voted against the stay, and I call them liberal, I hate to use that term, but the four justices who had voted against the stay

were all rendering individually dissenting opinions. You could draw the inference that the justices who were against you on Saturday were against you on Tuesday. And that's a good sign.

But even if, like, let's just imagine that all nine justices after hearing oral arguments, let's just say you had really screwed it up, all nine jud just to say, actually, we were wrong to issue to stay. Let's have this recaind on. I mean, time was up right at that point, it was over.

Well, I think the justices who dissented did not believe the seven of the nine justices believed that we had made legitimate, meritorious arguments on the equal protection and do process clause. The justices were five to four on whether or not the recount, the statewide recount that had been prescribed by the Florida Supreme Court had to be stopped.

So the other the four dessenting justices, for various different reasons, you have four different descending opinions there, for various different reasons, felt that somehow those statutory deadlines that were in federal law could somehow be adjusted or moved or something, that things could be done faster. I think that that assumed that things could happen faster than they could possibly be happening. If you had looked at the history we started off.

Was it November eighth, I think was the date of the election? Seven seventh, Okay, So we were starting this whole process was going in various different directions beginning with November seven. We were now at December tenth, December eleventh, December twelve, and we're running up against the various statutory deadlines, which culminated in a process that had to be finished in Washington in early January, and then there had to be a new president taking an oath of office on

the twentieth. And so I could not see how all of that could be done, and that the statewide recount was going to be and it was going to be different in every one of those sixty seven counties, and I could just see more chaos. And I think that the justices who voted with us with respect to stopping this entire process perceived that that was just going to be a continuing process, unfolding of chaos and people were still not going to find out who is going to be the president of the United States.

Yeah, right, okay, And final question. I read Evan Thomas's book about Justice O'Connor that just came out, and in there he has a quote from Scalia. It's not firsthand, but it says that Scalia privately scoffed that the equal protection rationale was, as we say in Brooklyn, a piece of shit. And I'm curious what your reaction is to that.

Well, my reaction is that that he felt, I believe, and what he meant by that is that we have a structural basis in the Constitution to decide this case. And it's in concurring opinion that the decisions with respect to the rules for the selection of the electors have to be decided by the legislature and not by the courts.

That's a simple, more straightforward ray of resolving it. He's always been, or he always was, someone that felt very strongly about the structure of the constitution, and he believed and he said this at his confirmation, hearing that people all over the world have wonderful bills of rights. The Pakistani constitution and the Iraqi Constitution and the constitution of the former Soviet Union had all kinds of really elegant sounding bills of rights. What has protected us in this

country is this structure of the separated powers. I know Many people, including many academics and other people in the political world, disagree with the whole process, But I think the United States Supreme Court did what it had to do, and it did it when it had to do it.

That was Ted Olsen, who argued on behalf of the Bush campaign in federal court back in two thousand, beca solicitor general in the Bush administration. Olsen died in November of twenty twenty four. David Boys, for his part, had not planned to be the one to argue Bush v.

Gore before the Supreme Court. That honor was supposed to go to Lawrence Tribe, the attorney who had been handling the Gore campaigns federal litigation efforts, but Boys got the call instead, leaving him scrambling to prepare his case, just like Olsen was doing at the same time. You had gone home right after the Florida Spreme Court ruling.

I thought my job was done. I thought that the votes were being counted, and even when the Florida vote count was stopped by the United States Supreme Court, I thought my job was over with because my job had been to argue the case in Florida, and there was a separate team that had been arguing the case in federal court. While I was actually in the air flying back to New York from Tallahassee, al Gore decided that he wanted me to do the argument in the United

States Supreme Court. I found that out when I landed.

I'm curious, like if you could just list the factors or dynamics that made this extraordinary or made this atypical for Supreme Court hearing.

I thought that the chances of the United States Supreme Court were going to change was going to change its mind were small. They'd already put a pretty big stake in the ground when they stopped the vote Counting in retrospect the way the argument unfolded, I think if anybody had had a chance to change somebody's mind, I had a better chance than anybody because I knew more about what was at the core. Remember that the primary issue Bush took the case the Supreme Court on was not

the equal protection issue. Equal protection issue was buried way deep in the brief. So the issues that I think we all thought we're going to be dispositive in terms of whether the courts could play a role or what role the courts could play in an election for electors.

Whether it counted was changing the law after the election exactly to change the certification deadline and then to order the recount.

Exactly whether you could do that under Article three of the Constitution.

And so that was was that. The Article three was the bulk of what you guys talked about during our arguments until Kennedy brought it up.

Yes, I mean it was. It was say it was buried deep in Bush's brief equal protection argument, and Ted didn't even get to it until late in his argument, after he'd been prompted twice.

How did you feel leaving the court that day? Did you realize when you left that equal protection would be the focus of the decision.

During the argument, I thought the argument was going very well. I thought that it was clear that Kennedy and probably O'Connor were not buying the Article three argument that Ted Olsen was making, and I was pretty encouraged, surprisingly encouraged. Then when Kennedy kept pushing the equal protection argument, I

became much more pessimistic. When I left the court, I was concerned because it sounded to me like Kennedy and O'Connor were searching for a way to sustain stopping the vote count, and I knew that the three most conservative justices were going to decide against us based on Article three, if nothing else. So it looked to me like I could count five votes against.

Where were you when the decision was handed down.

I was at my house in armac Armak, New York, and Westchester County got it.

The folks on television had some trouble understanding it in the first few minutes of reporting on it. Did you understand its implications right away? Or did it take you how many pages you have to read before you realized what it meant? Well?

I skipped to the end, but with a judicial opinion, I was trying to skip to the end at least to see how the court comes out. And it was clear that, as I had feared, there were five judges against us and the percurium opinion. It made clear that in my mind, the case was over with. And I think that it took a little while for people for that to sink in, but I think it eventually sunk in that there was no real alternative at that point. But to concede.

How did it affect your view of the Supreme Court that this ruling came down the way it did, and that it was justified in the way that it was. Did it change how you perceived this institution?

No, not really. I was disappointed. I think it's fair to say I was deeply disappointed. On the other hand, the Supreme Court during my lifetime has been probably the most powerful engine for social change in this country. The Supreme Court has made a number of really bad decisions over the years, but that does not, I think, diminish the importance of the Supreme Court to our society, to our constitution, to the preservation of the rights that are so important to our society.

Did it reveal to you that the institution is inherently political and that there's no way to avoid that.

Well, the Supreme Court was inherently political in the Japanese internment case, in the plus e v. Ferguson on segregation and dread Scott. The Supreme Court, like all human institutions, is influenced by politics. I think the thing that was most disappointing is that the political influence in prior cases tended to be the influence of people pursuing a particular

policy objective. Here, the Supreme Court was intervening to actually pick a President when they were intervening in a way that had partisan political implications that strikes at the fundamental principle of democracy that it is the people that decide elections, not government officials.

Thanks for listening to this bonus episode of Fiasco. We'll be back next week with one more featuring the late Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, whom we interviewed shortly before his death in twenty nineteen. Fiasco Bush v. Gore is produced by Prolog Projects and distributed by Pushkin Industries. The show is produced by Madelin Kaplan, Ulla Culpa, Andrew Parsons, and me Leon Nap. We had additional editorial support from

Lisa Chase and Daniel Riley. Thanks for listening. We'll see you next week.