Pushkin.

We felt like we had won, and when we got there and there were all these contests and all these questions, we thought that there was a effort in place to steal the election. Using the word stealing the election is just political hyperbole, and I don't usually use that, but I definitely felt that emotion.

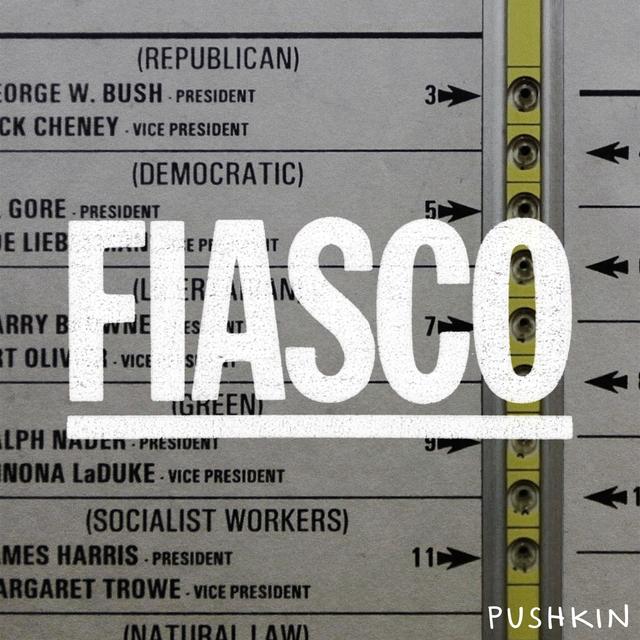

Hey, Fiasco listeners, this is Leon Apok. I hope you enjoyed listening to Bush v.

Gore.

Now that you've heard the whole show, we wanted to share with you some bonus material related to the two thousand election that we collected during our reporting process. We talked to around sixty people for the series, and though we included bits and pieces of most of those interviews in the episodes you've heard, there were a bunch of conversations where after we thought to ourselves, man, people should really hear more of this than we're able to include.

So in the spirit of using every part of the buffalo, we are bringing you six additional episodes in which you will hear my conversations with some of the most interesting people we spoke to. Today bringing you an interview I conducted with a Bush campaign staffer named Brian Noys. Noise served as a regional political director on the Bush campaign in two thousand. We were eager to talk to him because we wanted to talk to as many people from

the Bush side as we could. But we became even more interested when we learned about something he had been working on, an oral history project about the Bush Camp's experience of the Florida recount. As someone who had talked to dozens of people to try to piece together what happened during that process and why, I was immediately excited to compare notes with someone who had been doing something similar.

When we spoke, Noise told me about his experience working on the oral history project and what it was like for him and his colleagues back in two thousand when they were working on the ground in Florida. Noise started out by telling me where the idea for a Bush Team oral history came from.

We were coming up to the twentieth anniversary, and I actually have an older daughter who is in college, and one of her friends asked about me being involved in politics, and I went back through all my old boxes that

were very unorganized. It just kind of shoved in the garage and came across a lot of information from the election in two thousand and realized I had some memorabilia, and that started me reminiscing with friends, and we decided that instead of just telling each other these stories forever, we should probably record a few of them for my daughter and people like her friends who wanted to get kind of a first hand account of a historical event.

And so how long ago they just start working on it.

I think the idea germinated for a while, but we really took it on in earnest at the end of twenty eighteen. So we started, you know, identifying who we would want to be on, what kind of technical issues we would have to get over to record, the kind of things. But we we really kind of an interesting point for you is we are not recording Carl Rove or Karen Hughes or Joe albar Ben Ginsberg. We're trying to get the individuals that haven't been captured in all

the historical reviews in the past. There may be some crossover, but our real goal is to get, you know, people that are from Florida, the local representatives, as well as kind of a group of colleagues that were either Bush campaign or the volunteers professional volunteers that were part of it.

It's funny, it's so great to hear you. I mean to describe it that way, because you know, that's really the purpose of our show, too, is to try to find people who haven't those barely been canonized as part of the you know, people who get top billing in a in a movie like Recount or something.

Sure, well, let's view them as complementary projects exactly, all right, because we made a conscious decision to not do both sides and just literally focus on the Bush Cheney staff volunteers in Florida folks, and large part because after the election, a lot of us just didn't tell the stories on the record. And so I actually have interviewed somebody who has since passed, and so we're realizing our own mortality and the number of years that have passed since this.

And then if we're going to capture this for posterity, we need to do it in a way that you know, is respectful of the Bush legacy that we all worked for, but is personal enough that is interesting. And you know, otherwise people like me and a lot of the people they're involved in here wouldn't be in a historical record.

Yeah, well, that's great, what are you gonna do with that? I mean, are you gonna just really you sell the interviews or what's like the end product.

So we're really looking at probably three different products. One a book or some contemporary story or condensed narraty above it that we would hopefully release next year sometime, not a profit making thing, just to have it as a record, an oral history of all these and finding a presidential center or a museum that's interested in housing this, some reunions to kind of gather everybody twentieth adversary you do that type of thing, and hopefully have that in multiple

cities so that we would be able to maximize the people that can come together.

And you've heard all the stories, No, not all of.

Them, not all of them. There were probably a couple that people didn't want recorded.

There's one thing I've noticed, I wonder if you've if you've had this experience at all, there's been like a surprising number of competing theories of the case, Like what was the decisive thing that you know, led to the outcome that we had, And so everyone has like a moment in their mind where they think it, you know, decisively turned. Have you had that experience at all hearing that from people.

You know, what's funny is the majority of people I'm talking to are not attorneys, and so our experience, my experience in theirs was I had that gut feeling that we were going to win and that all was lost probably fifteen times during the thirty six days. So looking back at it now, it's kind of, you know, not the same perspective that I had at the time is to when it was really truly over. And that is one of the questions that I ask is you know, when was it that you felt like it was over?

And the majority of people that I talked to didn't release until the Supreme Court made his decision. There wasn't that moment after the first seventy two hours where you didn't feel like another shoe was going to drop, that

another court case would help you or hurt you. And whenever you felt good, you just weren't allowing yourself to celebrate and feel like you had hit a conclusion because you know, you just never knew when you know, another level of court or another level official was going to review this and change the rules. And this is not the project. This is kind of my personal recollection. You know, when we were in the counting room in Palm Beach, the Emergency Operations Center, when we had moved to the

bigger platform and we're doing all the precincts. Particularly in the first few days, there were so many moments where we thought they were getting an advantage, then all of a sudden they thought we were getting an advantage, and just never knew, you know, whether one counting station was going too fast and putting too many core votes out there, or whether you had, you know, things going into your advantage and it would just go minute by minute.

Well, it was like the lowest moment for you when you when you remember thinking that like you really were going to lose, or that the chances were, you know, as high as they felt at any at any other point.

Probably the two biggest points for me were when the Palm Beach County canvassing Board went from the one percent test to the full manual recount, because we knew it was a county that Gore had covered very well and there was a higher presented chance that he might make gains that would overturn us. The second time was when the Florida Supreme Court stepped in on right before Catherine Harris was going to certify, and they basically prevented her

from certifying. And so those were probably the two worst moments for me, because when loser draw, you accept it. When it's over, right, it's over, we move on to the next campaign. Well, this was never over. This was always in perpetually a state of anxiety as to when would it be over. And that's just kind of counterintuitive to a political operative.

Why that's specifically counter intuitive to a political operative.

Because you want an end date, So election day, when loser draw, it's over. And then each one of these decisions that would extend the election was just kind of new territory for me. It didn't compute. What do you mean, the campaign's continuing this efforts continuing the election was X number of days ago. You know, I was already away from my family for six months, and every day was just more excruciating that I wasn't with my wife and

young child. And you know, again, sometimes when you're that exhausted, you'll take a loss just because you want it to be over.

I can imagine before we get any further, I wanted just to make sure that I understand your job correctly. You served as the regional political director from all the states that touched the ocean or the Gulf of Mexico. Is that right correct? And you had Florida correct? How much of your like brain space did Florida take up during the campaign leading up to the election.

It was fifty percent for most of the time, and then going into the last month it was ninety percent.

Was there a time when when it felt to the Bush campaign like Florida was in the bag.

No, we always thought it was competitive.

You always thought they had a chance there.

Yeah, we always thought it was competitive. I mean the number is too big. I mean there's you look at Florida, this very diverse. We had advantages and they had advantages. You know, Jeb Bush is the name and the governor, and everybody pays attention to that. But you know, you had you know, law and Childs had just been the governor before him, and you had Democratic US senators. You had a balance of huge voter bases in the southeast

that counterweighted the entire rest of the state. So we knew we needed to have turnout in order to be successful.

It's interesting to hear you say that, because I think the Jeb Bush thing. It was what made them, the Democrats, or at least the Gore folks in Tallahassee, pretty pretty pessimistic. They felt like they gave the Bush campaign an advantage that they would were unlikely to overcome.

Well, I mean, think about it, Florida has had Democratic leaders on the state wide level too, and so they had just as many major donors, just as many volunteers historically that were available to them. They had, you know, Bob Butterworth, the Attorney General, was a you know, the top ranking Democrat I think on the state level. So

there's a lot of counterbalances to it. I mean the other thing too is from a practical level, Jeb was on the state canvassing board, but other than that, he had no authority over how the elections were managed at the local level.

And so why I think I think the people I talked to were saying more that it was an advantaged during the campaign because, for instance, because there were a lot of people in Florida who were would be reluctant to say donate to Gore because they didn't want, you know, to be out of favor with with the governor.

Well, I think there are some people in that category certainly, but there were also equal people that would want to be in favor with the incoming president and they would be working to get their favor with the Senator Gore. And so it again, the state was not clearly a red or blue state at the time. There was a lot of counterbalance.

I wonder if there was any sense on your end on the Bush side that, like after the convention specifically, they seemed to really focus on Florida and really it seemed to be in good position there, like post Lieberman's nomination, right, which obviously helped there. And then you know, I've been talking to folks about how after Jeb Bush's Action education policy there was a really really huge surge in African American voter registration.

I would concur with that, And I think technology and the way that you had information was just differ for twenty years ago, and so a lot of what you had was word of mouth and anecdotal and polling. So polling was a king at the time, but you could measure with a lot of that with any definitive level, and really not until we changed it in two thousand and four and then Obama changed it to another ratchet. It to another level. You really couldn't tell your intensity.

So we gazed our intensity by the absentee ballot program, and we had a very extensive absentee ballot program with a large turnout, and we thought we were doing extremely well.

And our Miami Dade kind of on the ground organizer, Cuban Fella, did tell me now in retrospect, you know, nineteen years later, that he did not anticipate the large numbers of African Americans and the turnout to match hours because he was so focused on it, and because Eleon Gonzales situation was so intense and there was so much of a fervor, they thought that, you know, our intensity couldn't be matched. And then on election day they did match it, and I mean it turned out to be

neck and neck all the way up and down. So I think he was probably a little surprised, only because he was so focused on our side and he knew we had an intensity. It wasn't that he underestimated. I just don't think he was even aware of it.

It's really satisfied to talk to you about this, and it's like, this is exactly the feeling we've been trying to conjure in the in the show, just that like there's so many little things that could be determinative.

Oh yeah, well, when there's I mean, when there's five hundred and thirty seven votes out of six million casts, you know, I probably can't even fathom all the different things that really could have affected it. From a state the size and is geographically diverse in two time zones as Florida, who knows what could have happened. That's why when we argue about the early call in the Central

time zone, how many votes does that affect? How many people turned around, didn't go to the polling stations in the Panhandle or left or whatever because they felt like it was a lost cause.

I've seen some Republicans say there was like ten thousand votes, which strikes me as a little bit.

It was a billion. You No, I can't quantify it.

So just let's let's le's boom zoom forward a little bit to the actual recount period. What was your understanding of what the Democrats were doing? Like did you think they were trying to steal the election? Did it that what it felt like or how did you conceive of like what they were up to?

We felt like we had won and when we got there and there were all these contests and all these questions, we thought that they were an effort in place to steal the election. And I say that with the political hyperbole that it is I personally the way I would describe it just day to day, I would say that, you know, we thought we had the lead, and they were taking efforts to you know, to change the rules that they would They were trying every way they could

to win, which is what you do. But you know, using the word stealing the election is just political hyperbole, and I don't usually use that, but I definitely felt that emotion at the time. I mean, the rules were the rules the day of election, and every time that there was a standard that was changed or a court decision that reset certain parameters, we felt like they were changing the rules after the election.

What rules.

So the butterfly ballot from the first twenty four hours and so on had become a political they were they were a political controversy. Rather so the the idea that you know, the election was not held in an appropriate fashion just didn't we We didn't agree with that that the butterfly ballot had been agreed to by the canvassing board.

You know that in a county that was largely controlled by local Democrats, a canvassing board that was you know, one elected official and two Democrats, and so we felt that there was no inherent Jeb Bush you know, fixed to change, you know Palm Beach. That actually was the reverse, is that the county officials were the ones that had determined the voting methods, and so if there was a disadvantage to Gore, it was probably a mistake, not an intentional issue.

I know this sounds cheesy, but I'm curious just if you could describe from sort of what it felt like to be on the receiving end of what you perceived to be an attempt to do something really unfair.

You know, Leon, to some degree, there wasn't a whole lot of feeling. You were just plowing through your day trying to figure out what a task you had accomplish. You know, what was the situation, How many people did you have to get in the room, you know, that level of basic logistics. There wasn't a whole lot of feeling. And then you know, you're working twenty hour days and at the end of the day, there wasn't much time for feeling because you were just basically falling exhausted into

a hotel room. I mean it was chaos for me personally too, because I had packed for three days. I went to one hotel and I changed in the first three days, I changed three different hotels because they weren't booking them for thirty six days. The logistics people, or even when I would just go sometimes to find an open hotel, they were like, say, how long are you gonna stay? And I would have to guess, you know, I'm not sure, maybe a week this time, and that

you had to restart. I got kicked out of one hotel one time in Palm Beach because of a girl softball tournament had come in and they would only book me up to like Saturday, And I said, but I have to stay through Sunday and they said, well tough.

Well, I know a lot of people got displaced in Tallahassee because of the Florida State game. Yeah, and they had to because I guess you will rent those hotel rooms like a year in advance.

Football is important.

Yeah. So one thing I'm interested in was this idea that the approach that the Bush side or the Republican side took during the recount process during those thirty six days was sort of a new thing for them. You know. Before the mid nineties, sure, Democrats were the ones who were sort of better at you know, on the ground activism or whatever, and that this election kind of changed that a little bit.

From my perspective, in the nineties, we were looking at a historical perspective where Republicans had not had complete control of Congress, meeting both House and Senate for probably four decades, and it wasn't until ninety four when that was my first real election in Georgia. Were working around new gamers and those folks when we took control of Congress, and that was historic because it had been decades since that

change had happened. And part of the political structure was Republicans had this, you know persona of being you know, presidential white, you know, more wealthy, economically oriented, and Democrats were viewed as more bootstrap union, you know, working on the ground kind of people. And Republican campaigns during that period were learning how to go knock on doors and do more of that type of stuff. But we really depended institutionally on direct mail and phone calls and television ads.

Well newt in that quote revolution started that change, but it didn't really come to fruition until after the two thousand election because that was that kind of wake up call that institutionally, the RNC and the political organizations outside of you know where like New York or Ohio, or those political organizations that existed forever in new places like Georgia, the Republican Party hadn't really existed, so we didn't have

the same kind of level grassroots. So in that two thousand election, we had the opinion that if we got into a scrap on the ground that we were going to get out numbered, that they were just going to institutionally have a better ground game than we did. And so we countered.

That, say you what does ground game mean? During the recount though, like the campaign's over, like what do you what's what's there to do?

Well, we had to learn so some of that was just an unknown, but we made the assumption that they were going to be better organized by filling those roles once we found them out. And so as we started learning what those roles were, we we filled volunteers in from every direction. So there's been a lot of historical view of the people who flew in from out of the state, but those were only a small subjection of

the total people that were volunteers. I can tell you for a fact, on the ground, particularly those first few days before planes could start flying in with other folks, ninety percent of the volunteers we had doing counting at the Emergency Operation Center were local Florida people. And then over time it probably evened out to a little bit

more fifty to fifty. And as a counting process was going along for more than a week or so, we would see we had a little bit of a system that would get worked out.

You're talking about the partisan the deservers.

Yes, but we didn't have one of those political organizations built at that level in Florida. We had an educations for Bush chair in every county. We had a veteran for Bush chair in every county. We had those law enforcement you know, for Bush organization in every county. But that was like a few people. We needed like literally hundreds of people to show up, and we threw everything we could at it, and we did feel like that the Democrats would have the advantage, but it didn't end

up being that way. I look back at it now, and I feel like we at least countered and then even to some points we actually outdid the Gore effort on that kind of local, grassroots bootstrap kind of a campaign.

All right, And I want to ask you one last question here. I haven't really no particularly strong instinct one way or the other as to whether you know Bus should have won or Gore should have won, or whether it was I just I sincerely just don't know and haven't known. But I've noticed myself sort of gravitating towards the Gore perspective, and as I'm writing the show, and I've been wondering why. And it's not because I think, you know, it's not because I wanted Gore to win.

It's because I think that it's because he lost, and because he was the one trying to reduce the margin and while Bush was just defending his margin, that there's sort of more inherently more interesting or inherently more dramatic story.

And I'm curious if you've in reading the books you know that have been written about this, and watching Recount and other other documentaries that have been made about this, do you feel like the Gore perspective is favored and do you think that the reaction that I'm having is in any way sort of related to it.

Well, yeah, it makes makes perfect sense that it would be more dramatic and be more intriguing because quote, what don't what don't we know or what could have changed to have changed the outcome? And you know, I'm pretty confident that we vetted it about as thoroughly as you possibly could. And the question is still it was really, really, really close, and Bush barely narrowed him out, but he did in fact narrow him out at every point in time,

so there was a lot of counterbalance. But on election day we had the win, and all the way through through Catherine Harris certifying and all the legal cases, the count never changed to favor Gore. So I have every confidence that we won by the narrowest of margins. But it's not as much fun to say, Okay, it's over. You know, you're looking at this because people do still have a question in their mind. So if you're intellectually curious, you could continue to just say, well, what if what

if that had changed? Or what if this had changed? And you're exactly right, but what if it is done? When the election is over?

Brian, this is such a pleasure, a truly unique interviewer, to be able to talk to someone who's who's seen it from from both inside and outside. The way you're doing with this oral history.

Well, I'll tell you I was I was not sure if I wanted to do this. I listened to your Clinton Lewinsky podcast burn and was very impressed. I thought you did a great job. Thank you so much, and I enjoyed it, and I hope you do as good a job with.

This me too. Thanks again. I look forward to someday hoping to hear those interviews.

Okay, great, all right, Thanks bye.

Fiasco. Bush v. Gore is produced by Prologue Projects and distributed by Pushkin Industries. The show is produced by Mattewan, kaplan Ulla Culpa, Andrew Parsons and me Leon Nafok. We had additional editorial support from Lisa Chase and Daniel Riley. Thanks for listening, See you next week.